Dedicated to discomfort: a personal history of the Everyman Theatre, Liverpool

Few theatre venues have cultivated their own mythology quite like Liverpool Everyman, but when I first crossed its threshold in 1995, I couldn’t help thinking, “What’s all the fuss?”. But that was far from the end of the story, and in this personal history of the venue, I get stuck into the reasons why it became the second theatrical love of my life.

Liverpool, it turned out, wasn’t like the city in the poems. There were no shocking pink hearts or bat signs over Lime Street, just a freezing wet trickle down my neck. It was January, the middle bit, in a city that had left Christmas far behind. No more tinsel, no fairy lights; just a dark afternoon, and me peering through the murk for its soul.

My girlfriend, Biddy, was with me too, and as we trudged up a hill, Liverpool tried its best to wash us back down to the river. The sky was an inky-fingered grey; the rain attacked as if on a mission to send us back home. I glanced at her, the woman I was hoping to persuade to move to this city with me, but she had her head down and her heart wrapped tight against the wind. Mine too began to freeze as I realised it was possible I would be making the life-changing journey alone.

“Are we going the right way?” she asked. “What’s this street called?”

At least Liverpool really does have a sense of humour, I thought, as I squinted at her through the downpour.

“You’ll never guess,” I said.

“What?”

“Mount Pleasant,” I replied.

—

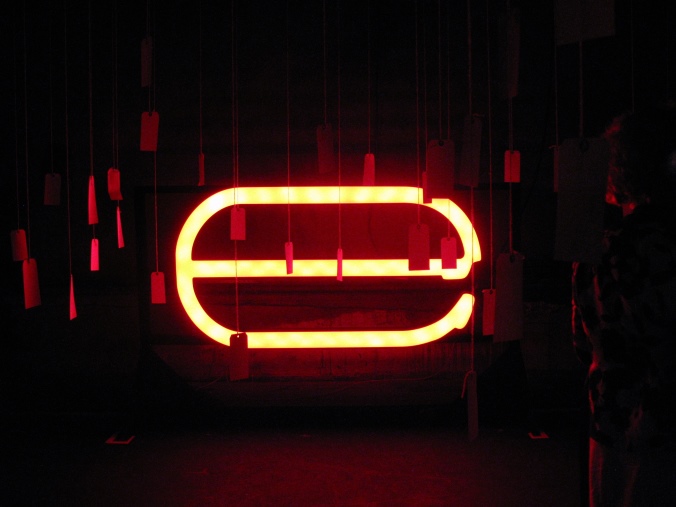

We were looking for the Everyman Theatre, a name that seemed to resonate with dramatic urgency although I was ignorant as to precisely why that was so. Without knowing much about its history as a fountain of counter-cultural endeavour throughout the 1960s and 1970s, or its emergence as a seat of Mersey absurdism as the 1980s ate Liverpool alive, it still spawned vivid images in my head: I saw bearded, open-necked playwrights banging at the typewriter while the Boys From The Blackstuff cast spat speeches over an audience in desert boots and flares. We’d been directed to Hope Street in search of this explosive theatrical furnace, but as we rounded the corner by the Catholic Cathedral, there was just the cold concrete bulk of a theatre that was crying out for love.

We stood there and stared, and I realised that Liverpool was once again playing ironic tricks with my heart. We were on Hope Street, but my own reservoir of hope was running dry.

I’d accepted a job in Liverpool and was finally ready to leave home in Sheffield behind. My years in the Crucible box office – where I’d met Biddy, who worked there too – had lasted at least 18 months longer than I’d planned; it was supposed to be a stop-gap, something to do while finding the writing job that would launch my career; but time was ticking onwards and though I adored working in that venue, I knew selling tickets couldn’t be the summation of my life.

But was Biddy ready to come with me? She seemed curious but far from certain. And thus I decided that the best way to demonstrate that there was a life waiting for us by the Mersey was to spend an afternoon wandering Liverpool’s streets, admiring its architecture, sucking up its cheeky scouse spirit. We might even, if we were lucky, find her a job in a theatre box office – somewhere just like the Crucible, the venue that had cast such a spell over our lives.

I gazed across Hope Street at the Everyman. The building was clenched like a fist; it looked as welcoming as a punch in the face. My eyes dampened, not with tears but with rain. I thought of the familiar grey bunker of the Crucible back home – no less brazen in its harsh concrete angles, but with great panels of glass through which could be glimpsed colour and activity and life. The Everyman offered no such relief; through the shadows, it looked padlocked, slammed shut.

Crossing the road, we expected to find the door immovable and obstructive, but to our surprise it swung open when we pushed. Inside though, the foyer was little more than a dark corridor built of brown brick; there appeared to be no one around.

“Can I help you?” came a voice, and we realised that there was a presence watching over us through a small window; it was a man, and he appeared to be sitting in little more than a cupboard. We smiled, though unconvincingly; it dawned on us both that this window was the Everyman box office, and the man, who was alone, represented the entirety of the ticket sales staff.

Again, a vision of the Crucible strobed before my eyes: with its four wide open counters that greeted visitors like a smile, it felt a breed apart from this lonely portal. The man was friendly enough of course, for how was he to know we were viewing him through disillusioned eyes? We asked about vacancies and he gave us the manager’s name, and as we back-pedalled towards the door, we asked if there was anywhere nearby to get a drink. We’d been hoping for a theatre coffee shop or even a bar, but on the evidence of its darkened interior, the Everyman offered no such treats.

“Downstairs,” he said. “You’ll find everything you want in the basement.”

It prickles my eyes to think about it now. There was the steep rake of stairs, our hesitant shuffle, a few steps down into the unknown. But as we emerged into a low ceilinged cavern of artificial light, we both realised that here, beneath a theatre with a celebrated heritage but an uncertain future, was a haven we could truly call home. There were large tables ringed with happy Liverpudlians; plates piled high with pastas and casseroles and quiche; there were beers and coffee and fag smoke; and because it had no windows, it was a paradise that was hidden out of sight.

I don’t think we even realised at the time, but we were in the Everyman Bistro, an establishment umbilically connected to the theatre upstairs and yet also somewhere to savour in its own right. As we bought drinks and sat in a corner to thaw, I immediately thought of Educating Rita and the bohemian wine bar world in which she blooms, with its students and actors and poets and piss-heads; and I wondered whether this heaving vault had fertilised Willy Russell’s imagination. I’m sure now that the answer is yes.

And as the warmth of the booze crept up from our toes, I felt then that my mission might have a happy conclusion. It was undoubtedly the worst day of the year on which to impress a wary visitor, but in the Everyman we realised that this famously brutalised city was very very much alive.

The day ended with a snow storm, with a frozen train ride to Sheffield, with cancelled buses and an arctic plod back home to our flat. But a month later, I returned to Liverpool for good – to begin my new job and tune in to its lairy west coast perspective. And a few weeks after that, Biddy came too – to live a shared life with the Everyman at its heart.

But… how so?

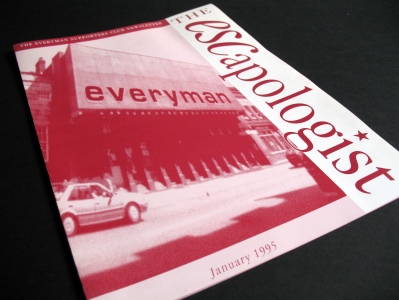

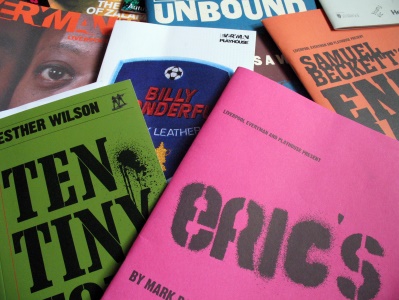

It happened thanks to that hoped-for box office job, which came her way within a couple of months, and through just going to the Everyman and witnessing its wares. Not that it was a theatre in its prime; this was early 1995, and the Everyman had only recently reopened after a period of total darkness. It had been rescued by the proprietors of that cellar bistro, who bought the whole building; they no doubt understood all too well that they needed a thriving theatre upstairs, but so entwined were they with Liverpool’s cultural edgelands that I’m sure they realised the city needed it too – whether it realised it or not. And now, here it was: a theatre with a sporadically firing programme and an undeniable shabby charm, being coaxed back to whimpering life. It was attempting to raise itself from the dead on the most frugal of budgets, bringing in decent shows on tour but rarely able to invest in productions of its own.

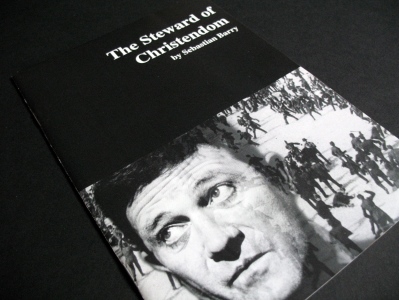

The first drama I saw there was good stuff – The Steward of Christendom by Sebastian Barry – but my fascination with the theatre’s physical details got the better of my devotion to the drama. It was more tarted up church hall than state of the art, with tattered bum-worn seating and lots of make-do-and-mend. I was pleased to see it had a thrust stage – like the Crucible – but it felt more like haphazard happenstance rather than the product of a singular theatrical vision: the Crucible stage’s dimensions had been determined under the guiding hand of Sir Tyrone Guthrie, by declaiming classic Shakespearean speeches, by pacing through Henry V. The Everyman’s stage, on the other hand, appeared to be just a size and shape that happened to fit.

The two side banks of seating weren’t actually seats, but were old church pews – hard benches with stiff upright backs: it was almost a parody of the puritan socialist ethic; a hair-shirt brand of drama where nothing was meant to be too much fun. In 1977 – the last time the theatre had been renovated, when its maudlin Victorian frontage had been lopped off and replaced by a brutish brown concrete slab – this dedication to discomfort must have seemed part and parcel of a non-bourgeois dramatic art, but almost 20 years later, post-Thatcher, it carried more than a whiff of Dave Spart.

I imagined the space as it once might have been: hectic with sounds of argument and polemic; alive with beards and cheese-cloth and Indian dresses, and pamphlets hurled in anger at the stage. If I turned my nose to the air I could pick up the scent of brown rice and lentils bubbling up from the bistro below, the muddy spiced scent from the building being mixed with the discharge from an idling 2CV in the street.

But these were spectral stimulations; the Everyman of 1995 had a less idealistic mission in mind. It simply had to survive in the hope that if it stuck around long enough, and reminded Liverpool it was there, it might build the momentum that would bring back its mojo and earn respect based on its present as well as its past. I admit though, I wasn’t confident: it was manned by a close-knit crew who understood its true value, but it seemed to have lost so much of the magic that had fuelled its myth: it was missing its celebrated youth theatre, which was operating independently until such time as its destitute parent was flush enough to welcome it home; and in spite of its best intentions, it had lost the artistic coherence – whether kitchen sinky or sci-fi surreal – that had once helped make its name.

When Terry Hands, Peter James and Martin Jenkins founded the Everyman Theatre in 1964, they plugged into the energy that had powered the building’s immediate past. Originally a chapel, then a cinema, ‘Hope Hall’ as it was known had, by the early 1960s, become one of the centres of Liverpool’s extraordinary cultural boom. The Cavern we know about of course; but Hope Hall was also drawing in explosive vapours of its own – vapours that the city’s art community was all too ready to ignite. They were poets, they were painters, and they were happening; and when their own Hope Street venue – previously host to live art and performance of a polo-necked persuasion – became a theatre committed to raw dramatic experience without the refinements of the Playhouse down the road, it seemed to capture not just a spirit of the times, but also an essence of out-there, on-the-brink Liverpool culture.

Living always on the edge of ruin, the Everyman’s primitive surroundings and primal power were what propelled it into the 1970s. As Liverpool’s hair grew longer (and the bistro took over the building’s cellar for what would be a 40-year stay), the battering dished out by the global economy turned the city’s wise-cracking smile into a sardonic sneer, and under the direction of Alan Dossor, the theatre began to raise issues and raise consciousness – not to mention weaning one of the most richly talented young rep companies ever to paint its own scenery. In an era when Play for Today bled into Black Stuff and then Channel Four, the Everyman generation’s skill at delivering both the grit and the grin was a gift to public service broadcasting.

Then at the twist of the next decade, there was another significant lurch for the Ev, as Ken Campbell was appointed artistic director. He was the progenitor of epic esoteric cartoons that divined for the secrets of the universe, channelling the stream of Mersey surrealism that already flowed down Mathew Street – thanks to Peter O’Halligan’s Liverpool School of Language, Music, Dream and Pun, along with Campbell’s own Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool – and allowing its spirit to pour through one unique Everyman season.

But these weren’t the Everymans – the Everymen – in which I sat and dreamed. Those days had gone, and I found myself falling for the theatre more for what it had been than what it could be. The Everyman had never been a purpose-built, paternalistic gift to the city like the Sheffield Crucible (which was a gift that wasn’t necessarily always welcomed if truth be told); it seemed to have sprung into existence because there were creative forces in Liverpool that simply needed it to be there, and I imagined that this was why it had come back from the dead, why it was biding its time.

Liverpool without the Everyman seemed untenable.

—

As I write, exactly 19 years have passed since Biddy and I walked up Mount Pleasant in the hope of a life-changing theatrical encounter. We got one, though not quite in the way we might have planned. Instead of an instant piercing by Cupid’s arrow, it’s been a tentative creeping of love, as much a product of friendships and attachments to the Everyman’s extended family as to the searing intensities of its drama – though there have been plenty such moments down the years. But now, as an unscripted future encroaches, I can safely say that the Everyman has wound its way round our hearts.

The last ten years of those 19 have seen the Everyman re-emerge as a theatre thriving on more than just history – still hidden behind brown concrete (until now), but active and interesting within. Under artistic director Gemma Bodinetz, and in administrative partnership with the Liverpool Playhouse, it has self-consciously blended the myths of its past with a current of artistic endeavour that nurtures new writing, that favours powerful stories with a Liverpool edge, and that wants to feel loved by the city. This love can wax and wane, but even in an empty Everyman, there are so many ghosts that you never feel entirely alone.

It’s late February 2014. In a few days’ time, a brand new Everyman building will open on the site of the original; we said goodbye to the old place in July 2011, when its by then near-decrepit facilities were closed up for demolition, and we’ll be there to welcome it back when the lights on its new non-concrete edifice are finally switched on next week. There will be those in Liverpool who feel that the demolition of that familiar elevation – a brutal face stitched onto an exhausted frame – will drive out the spirits that gave the Everyman its magic, and a few of those people will perhaps never return. But that’s not how I feel. That there is an energy on that famous street is undeniable – nothing mystic; I mean an energy fired by collective history, by memory and hope – and I’m sure the new building will take time to tap its source, but it will happen. We should be thankful, really, that the Everyman had created the need for its own replacement, because that means it still matters; and remember that the memories of the young are short. As the young people of its youth theatre grow (a youth theatre now returned to its roots), the Everyman Theatre of 2014 will become the empty vessel that they fill with noise, and before long, it will be wisped through with spectres of its own.

At which point, I must declare a further interest.

In place of that forbidding brown concrete slab, first glimpsed through the rain 19 years ago, the architects of the impending Everyman have designed a screen of aluminium shutters that protect the glass walled offices along the front of the façade. Each shutter is around three metres tall and is pierced with the image of a Liverpool citizen; the effect is such that when viewed from a distance, the realist photographic illusion is complete and it becomes difficult to believe that it’s simply a matter of holes sliced through metal.

In many ways it’s a concept of crude simplicity: “every man”, you see? Or rather, representatives of every man, woman and child in the city. Not actors or characters or figments of the imagination, but actual Liverpudlians who turned up to have their pictures taken and were lucky enough to make the cut. But if the concept is unsubtle, its implementation seems astonishingly elegant. Since the end of 2013, these shutters – these people – have been exposed to the Liverpool winter as the building has approached completion, and even without a fully operational theatre living its life around them, they have prompted gasps from pedestrians as they’ve turned that Mount Pleasant corner.

And on the top row, third from left, is my youngest son, snapped one Saturday morning in baseball cap and mucky trainers, now captured in a slight turn to the camera, an unchanging nine years of age. The shutters are a permanent fixture, or at least, they’re intended to be decades in place – until the weathering caused by that winter rain brings them to the end of their life. So for the next – how many years? Twenty? Thirty? Forty? – my son will watch over Liverpool from the Hope Street ridge, head full of PlayStations and comics and school.

If Biddy and I had known that as we searched for the Everyman 19 years ago, our underwhelming first impression might have been a wallop in the heart, and the water streaming down our faces would have sprung from a saltier source.

It may seem perverse to end this story just as the Everyman is about to be reborn, but while there is much to be discussed about the attempt to capture old magic in a new space, it feels like a different tale to me. There will be lots to be said, no doubt, but these words are simply about why it’s all important; why this venue is more than just another place to see a show.

Theatre professionals will often insist that it’s the work that matters, not the space in which it occurs, but I’ve never been able to agree. Theatre buildings are where the hopes and dreams accumulate, and while the actors and directors move on, it’s the audiences that create the web of memory that snags them each time they return.

I met my wife at the Crucible. I printed my son on the Everyman.

So while somewhere like the National Theatre is probably good and everything, I don’t think it can ever match that, do you?

Text © Damon Fairclough 2014

Images © Damon Fairclough 2011 and 2014

Such has been the Everyman’s staggering ability to set actors and writers on a path to international renown – not just by welcoming them in, but by moulding their early careers – that had I begun listing them, I wouldn’t have known where to stop. So with a couple of exceptions, I’ve deliberately avoided naming all the names and notable productions. But should you wish to delve further into the details of the theatre’s history, you can’t do better than Ros Merkin’s exhaustive book ‘Liverpool’s Third Cathedral’, which was published in 2004 for the theatre’s 40th anniversary.

More writing about theatre on Noise Heat Power:

An argument in concrete – A personal history of the Crucible Theatre

The Crucible method – Forty years of the Sheffield Crucible

For the Lyceum with love – A brief history of the Sheffield Lyceum

Share this article

Follow me