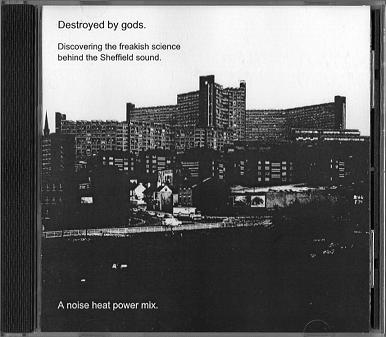

Destroyed by gods: a Sheffield music mix

From Cabaret Voltaire to Pulp, Human League and The Box, this stainless, steely-edged music mix goes where rust fears to tread. Open your heart and discover the freakish science behind the Sheffield sound.

Some bands just had to come from a certain place. Others just happened to be there. The latter are often confused with the former – but it’s the former that make city music scenes matter. It’s a mysterious thing, but I’m afraid it seems true, that some cities take on a musical form and sing while others just offer up lists of bands that are… well… just lists of bands.

Why does the magic sometimes happen… and sometimes not?

It’s to do with the people and the place. It’s to do with the time and the inclination. Sometimes it’s about mutual support. Other times it’s about cut-throat competition. It’s about the technology, and the landscape, and the venues. It’s about the history too, because once there’s a history – once the mystical transformation from street plan into sound wave has occurred – it will have a tendency to occur again. It’s about self-awareness, and naivety, and pride and denial.

What you can’t do is prescribe it and make it happen. Once the conditions are right, the sound becomes the city and the city becomes the sound. But it’s instinctive, and it’s self-fulfilling, and you know when it’s true. You can’t make it up, you really can’t. There is no sound of Leeds. There is no Preston beat. There are bands and musicians from both these places, but those cities have never become something else through sound. They remain bricks and mortar, flesh and blood.

Sheffield is a city that does exist in this ephemeral form. Its sound is industry. It’s pop. It’s electronic. And it’s raw. It’s a narrative with its feet on the ground and its head in the clouds. Somewhere, without or within, it’s glamorous – but like all the best glamour, it only comes out at night.

Sheffield is the old flame that inspired a collection of music called Destroyed By Gods. I selected the tracks, and I mixed them using the powers of witchcraft. Then I burned them on a CD, and I listen to them to conjure up grey concrete dreams, a Sheffield of the ears and the mind. Running through each track is a common core of… well, that’s the thing about music. It denies words, even while it urges me to write it all down. So those emotions, those feelings, that simple sense of place – I can’t stop my fingers tapping this keyboard, but whether I’ll get it right is a different matter indeed.

You can download the mix in MP3 form by clicking here. Listen hard, and see if you can hear the sound of the city I’ve been known to love.

Track one

All Seeing I – The Gods And Sheffield (1999)

“Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first send to Sheffield.” And that’s all you need here – just those few words, and the tweets and burbles that follow. Because the job of this track is just to set the scene and introduce you to the sound place that is a certain Yorkshire city, a point at the south of the north which, to the uninitiated, might even be called the midlands! So is Sheffield good only for the destruction of the soul? As long as the rest of the world thinks so, we get to keep the secret of the city to ourselves. And somehow, our innermost thoughts end up coming out like this…

Track two

Human League – Being Boiled (album version) (1980)

“OK, ready. Let’s do it.” That’s how Being Boiled should start. That’s the cold, hard, stripped-down original, with the bassline pulsed by an arrhythmic heart. Of course, it’s the original, and it’s the best. So why launch a collection of stainless Sheffield music with this florid and trumpety album version, taken from 1980’s Travelogue? Hmm. Simply because right here, right now, it’s what we need.

Put it this way. Park Hill flats is the quintessential Sheffield landmark, but if you were deep in Thatcher’s recession and were introducing a mate from, oh I don’t know, Reading, to the city, you might ease them in with a night out at Josephine’s before giving them the primer course in post-war social housing policy – on the basis that it’s still Sheffield through and through, but at least it glistens. You wouldn’t march them straight up to Park Hill’s top balcony for a night admiring the brutality of the concrete. Well, unless you lived there.

So that’s the album version of ‘Being Boiled’. Compared to the original’s brave new architectural sound scheme, it’s a night out in Josies’.

Bottle of birthday bubbly and a fist fight at the cab rank anyone?

Track three

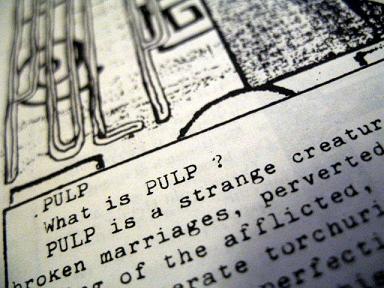

Pulp – Joyriders (1994)

Ja-jinggggg. “We like driving on a Saturday night, past the leisure centre, left at the lights.”

From our trip with the League round Sheffield’s outer spaces, Jarvis drives us back into town in a converted kitchen sink. And doesn’t he just sum up everything about growing up in that time and that place? When your head swam with dreams and the concrete ran with tears, and there was always someone who thought you were just bloody weird?

“Hey you! You in the Jesus sandals! Wouldn’t you like to come over and watch some vandals, smashing up someone’s home?”

The story of Pulp’s – well, Jarvis’s – long wait for stardom is well documented. But if you studied the pastings and the peelings of Sheffield’s eighties flyposters, then Pulp was a name you knew well. Always appearing somewhere near you – the Hallamshire maybe, or the George IV – they seemed to crackle with Sheffield static. Draped in bog roll or wrapped up in foil, a Pulp stage was no ordinary place. Like a corner shop’s Christmas grotto, it was budget glam with a jumble sale Santa. What would he get up to if you ever sat on his knee? What indeed…

It’s the details that tell you how well Jarvis knew his subject. Because these joyriders don’t indulge in generic naughtiness; their goals are specific to the time, and again, the place.

“Mister, we just want your car. ‘Cos we’re taking a girl to the reservoir.”

With that rhyme, Jarvis gets it oh-so-right.

The reservoir.

So easy to get to from Sheffield, the Ladybower reservoir is a mirror in the mountains where Sheffield gathers to reflect on the day. In summer ’76, we drove there just to wonder where the water had gone. On Sunday afternoons, we go for ‘a run out’ with our grandparents. We tell stories about the villages that were flooded to provide us with water, and we imagine the churches and pubs and homes that might, or might not, be still there beneath the surface.

It’s washed over our leisure time for so long that even the bad boys – the joyriders – know it’s the place to go and kill time. Sitting in your car, gazing at the water, unwrapping a Fletcher’s bread sandwich of grey and fibrous potted meat.

Now that’s what I call a joy ride.

Track four

Heaven 17 – Play To Win (1981)

The Human League seemed to invent a certain way with synthesisers. Wendy Carlos and Jean-Jacques Perrey had taken these brand new boxes and marched off in one direction – a direction that took us into a world of classical pastiches, crossed wires and novelty bubblings. But the League took theirs into a darkened room stuffed with Roxy and Bowie vinyl, then they shut out Sheffield’s light and with one slooooow-moving finger, pressed ‘ON’.

The results were ponderous. Sci-fi. Skeletal. They throbbed with a steady Art beat. Kraftwerk were about the humanity of progress – but in the there and then of motorways, calculators and nuclear power; the League were in a parallel universe of hit records that swallowed all before them, crow/baby interspecies breeding, and long-lost radio messages from the future. They were flickering TVs, sparking fuse boxes and overloaded power stations, all celebrated with a portentous frown and a non-shifting dance-stance.

And reading between the lines, it all became too much.

Specifically, too much critical respect without the public adulation to match. And almost inevitably, different people sought different ways to redress that balance. One way was Phil’s: pure electronic pop that would be both in vogue, and in Vogue. The other way was Ian and Martin’s: electro-funk designed to excite the masses to revolutions both musical and political.

There was much unhappiness along the way – “I was being thrown out of my own group, the group I started with Ian,” as Martin Ware puts it in Eve Wood’s Made In Sheffield documentary film – though the opinion of most seemed to be that his musical horse was the only one riding to future commercial glory.

Ian and Martin were, after all, the talent. Musical, studio-friendly and gadget-aware, they upped the soul and chopped at some jagged guitars for a playing-at-playing-some funk sound with a very self-conscious groove.

So that was Heaven 17 before they found true fame. Playful, spare and dry, this track’s synthetic brass stabs and jaunty whistle tread lightly through a northern soul landscape of desperate ambition. That certain way with synthesisers that the Human League made their own was left in a shadowy corner of the 1970s (not forever, but for long enough) and Sheffield suddenly found its feet moving, its arms flailing. It was dancing all right, but what with Thatcher and everything, it honestly seemed to be dancing to destruction.

Track five

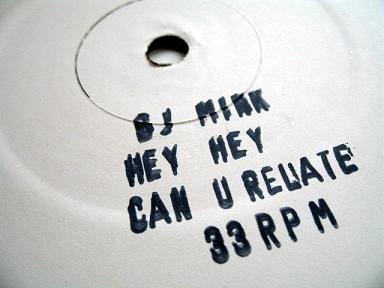

DJ Mink – Hey! Hey! Can You Relate? (1990)

Having started a knees-up of sorts with Heaven 17, the block party whistles and “Woo hoo hoos” of DJ Mink’s Hey! Hey! Can You Relate? make for a perfect mix that keeps the feet moving.

This whirling hip-hop also manages a neat feat of memory, being both a forgotten gem and a revered classic, depending on which circles you move in. As the fourth release on the nascent Warp Records, a label that turned the echoes of Sheffield’s past into a sonic boom that still reverberates today, it was hurled into a world of bedroom techno that, against all the odds, was destined for chart success and sound-of-an-era aural domination. With label-mates sharing a four-to-the-floor thump, spacey bleeps and a black-British bottom end, this track’s whipcracking breakbeats and breathless rap marked it out as something else entirely.

And thus, as Warp was sprayed with a ‘techno’ tag, DJ Mink’s finest (only?) moment slipped back into its sleeve and was shelved as an atypical period curio.

Over in the hip-hop community though, the track grew and grew and grew. Guaranteed to blow up a party any time, anywhere, the opening vocal salvo is a scatter-gun syllable spray:

“Stop look and listen the position you wish you was in, words coming out from the power within.”

Not that words came out from the power within every version of this track, and it’s probably true to say that the accompanying Rob Gordon instrumental remixes gave the track its true 0742 identity. Rob was a Warp founder, as well as being the producer who perfected the sparse, bass-heavy techno sound of the time; he held the welder’s mask as Warp forged a distinctive, local dance music. But having given him his due here – and he’ll be back in this mix before long – we stick with the raw hip-hop of the original, words and all.

We’re having a party after all, and we need to make the most of it. Because it’s about to come to a stop…

Track six

Artery – Afterwards (1982)

“Afterwards you wrote, if I ever see you again, it will be, too soon. I was so, confused…”

Worryingly-intense boys have always had it in them to make great music. We’re familiar with the glacial Joy Division of course, but it seems to me now that Artery ran them close – or would have done, with a producer like Martin Hannett to really lower the temperature.

Why do I think this? Well, because the people who saw them say so. I didn’t see them. I don’t even remember them. But Mark Sturdy’s book about Pulp, Truth And Beauty, serves as a generously proportioned primer for all those who may have been too young, or too geographically challenged, to recall the details of Sheffield’s early eighties scene.

And in that book, and the Made In Sheffield documentary, we learn that Jarvis loved to lose himself in an atmosphere of “mild hysteria” while experiencing Artery. Or rather, he may not have loved the hysteria, but he was witness to it, and part of it, so that when singer Mark Gouldthorpe spirited himself onto a perilous window-ledge above a city centre street, it just seemed to be the kind of thing that would happen to a man playing music like this.

Even now, we can glimpse something of this tumult on the Made In Sheffield DVD. Stashed away with the extra features is a recording of this song filmed in Leeds in 1980. Blood red and dangerously unpredictable, it twists into a hollow, desolate groove, and Gouldthorpe falls Curtis-like to the floor, twitching desperately, terminally.

When I hear this, I wish I could have seen them. I wish I could be talking about them now with more than third-hand knowledge, because they were almost inevitably much more than the recordings can ever be. They took Sheffield music’s taste for amateur theatricals and added lashings of threat, portent and mystery.

Go up Shirecliffe on a dark blustery night, and you can still hear them on the wind.

Track seven

I’m So Hollow – Touch (1980)

If garage bands were so named because they played in garages, whatever happened to cellar music? And attic combos? Because where I come from, cellars and attics were the engine rooms of countless semi-bands, the reality of whose ambition reached no further than the matted spider webs and flaking plaster that brushed off the walls as you passed.

This track by I’m So Hollow carries the dank odour of a Sheffield cellar, though I wouldn’t presume to assume the extent of their ambitions – I’m sure they hoped their mumbling guitars and rumbling drums would chill a Top Of The Pops studio one day.

But…

Worn demo cassettes. Rooms above pubs. Amps lugged down stone steps. Guitars that are clammy to the touch.

That’s what Touch sounds like to me. But as it lurches forward, vocals straining, it begins to bubble with a stuttering synth that takes it somewhere else, out of the cellar and towards the air. Pushing past Vileda Supermops and tins of Vim, it thrusts itself into what it hopes is blazing light, only to find itself in yet another musty hole.

When everything you touch flakes away in your hand, you’re fated to make cellar music forever.

Track eight

Cabaret Voltaire – Sensoria (1984)

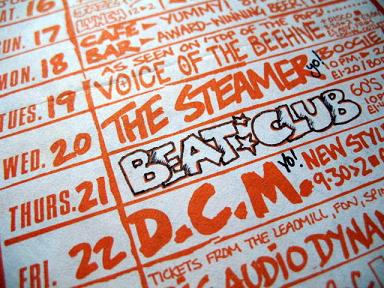

For years, I went to the Leadmill every Friday night. And sometimes Thursdays too. And the occasional Wednesday.

There were other nights as well, but I hesitate to go on because it suddenly looks as though there was nowhere else to go in mid-eighties Sheffield.

Hmmm.

The Leadmill still exists of course, and it remains well known. But it is now simply a successful club and gig venue with a national reputation. And once upon a time it was very nearly something else entirely.

Always vaguely worthy yet always more than interesting, the Leadmill was a quirk of nature that just was what it was. A bit like a venue for bands and a bit like an ‘alternative’ nightclub, it also hosted long seasons of fringe theatre and performance art, poetry and circus workshops, served lentil-heavy wholefood in its sticky-tabled cafe, and presented Sunday dinnertime (by which I mean lunch time) live jazz.

Housed in a dark brick shed opposite the bus depot, the Leadmill was two large interconnected rooms with a warren of offices and studios above. At the very top of the building – about four floors up – was a large loft space draped in sticky screen-prints that smelt deliciously of printing inks. From here, Martin Bedford created all the Leadmill’s print publicity, fashioning fine graphic art for bands big and small.

If you snuck up some narrow stairs behind the door next to the cloak room, you came to the main admin office where man-in-charge Adrian Vinken lived. I know this because in 1986 I snuck up those stairs and walked into the middle of a meeting, just so I could get permission to take some photographs during a gig. “No problem,” he said, and the meeting continued as I scuttled away.

Exactly the sort of dynamic individual that keeps cities interesting in desolate times, Adrian was adept at conjuring funding from the ether, and tethering the many points-of-view involved in running a co-operative venture to the need to keep things real.

So the Leadmill was a place I came to know well. And as I said, every Friday I was there with my black combat trousers and thickly-gelled hair, having squeeeeezed through the suffocatingly-tight turnstile (salvaged from an abandoned football ground) and paid my quid (unwaged, as was the terminology of the time). You emerged between DJ booth and pre-historic bogs, and in front of you was the dancefloor – usually empty at that time of night. Over to your left was the cafe. On your right was the second room, where you bought your booze.

The bar was a long stone affair lined with real-ale pumps – a selection of beers that betrayed the beardy philosophies behind the place. So as we danced to The Smiths and Grandmaster Flash and Prince in our 8-hole Dockers, we gulped pints of Marston’s Pedigree and were kind of satisfied with what we had: ragged UB40s, miners’ benefit gigs, and tumbledown squats where our industry used to be.

Not that this was heaven. The Sheffielder’s tendency is to be ‘not fussed’, to mumble and moan even when we’re paying for a good time. And while there really was no alternative if you weren’t down with the townies or the rockers (a slight exaggeration, as there was always the Limit, though for me, it was well named and I seldom went), the fact that you could predict the playlist’s eccentricities meant that ‘not fussed’ was what you generally were while in the Leadmill.

Just before midnight, the tub-thumping psycho-folk of The Pogues’ Sally Maclennane would churn up the dancefloor, then Glenn Miller’s In The Mood would see in the Saturday in a jolly – but misplaced – kind of way. And it was the same every week. Fun the first few times but then… why?

On equally heavy rotation for a while was Cabaret Voltaire’s Sensoria (I knew we’d get there eventually). It still conjures up the huge echoes of that acoustically-challenged main Leadmill room, and the stumbling thump of the drum beat still reminds me that it really isn’t easy to dance to – like much of the Cabs’ mid-eighties dance tracks in fact.

Yet still it pumps, and still it bumps, and while it rattles and hums with vocal cut-ups and splices, its effect is like gleaming steel compared to the Cabs’ murky pig iron tracks of the 1970s – my Sensoria 12″ is as flat and black as a molasses pancake, and it’s cut so loud it still echoes across the universe. It never struck commercial gold, but it was an anthem of sorts for so many who lived beyond the 1980s’ floppy fringes – in Sheffield or otherwise.

The video was a disorientating delight created by Pete Care, a graduate of Sheffield Polytechnic’s Psalter Lane art campus, where film, video and sound were equals alongside painting, sculpture and print; those edit suites and cameras helped create Sheffield’s music/image interface, and were the reason that the likes of the Cabs and the Human League were able to make visuals a central part of their performance. A few slides and some 16mm footage, and suddenly you were leading where, years later, everyone else would follow.

So while Cabaret Voltaire had been ten years in the making when Sensoria was released, and the rawness and sense of revolution in their earlier tracks had gone, it’s this tune that stays with me the most. It always brings back Friday nights and beer and dancing and that long walk home.

Quiet Sheffield. On-my-own Sheffield.

Exquisite Sheffield.

Track nine

Human League – Marianne (1980)

With their low budget sci-fi electronics – Blake’s Seven rendered in musical form – the Human League sparked up some artful narratives and imaginative mini-sagas. The Phil Oakey spoken monologue was used to great effect on a number of occasions to cut to the quick of the story – “With concentration, my size increased, and now I’m 14 storeys high, at least…” he assured us on Empire State Human; in The Black Hit Of Space, he reaches for his record deck’s tone arm “…which was less than one micron long but weighed more than Saturn…”.

It’s Jackanory… but penned by J.G. Ballard.

But what about women? Where were the women in this well-thumbed, paperbacked, boy’s bedroom world? And if there were women there, could they be real? Or would they be Princess Leia? Barbarella? Or Jenny Agutter in Logan’s Run?

Well, here’s Marianne. In what seems to me to be a lament from a father for his now grown-up daughter, and the loss of the life that was her as a child – “All that’s left, is the space, in a life. That goes on as before” – we have heartbreak and human relations without the filter of fantasy. There’s an irresistible chorus with real hooky melody, a hint of where the League would Dare to tread in the near-far future. There are multiple lines sung simultaneously. There are synth chirrups and a stark, crashing beat.

Marianne is a desperate voice calling to the suddenly-vanished past – but in the manner of the suddenly-close future. It’s pop, and experiment, and good old-fashioned emotion.

It’s thrilling. But having visited our adult selves, and realised what’s in store for us in the 1990s and beyond, isn’t it time we got back to the dance?

Track ten

Sweet Exorcist – Testfour (1990)

It opens with a quote from Close Encounters.

It continues with two recording studio ‘test tones’ played in sequence – boop beep – then in reverse – beep boop.

In comes an atonal and percussive 909. A few bars of that, then some kind of Gregorian chant-like hum.

“Everything’s ready…”

Then… the bass. Growling, throbbing, gut-churning bass.

When we heard that bass, we knew Sheffield was back. Those years of sonic experiment were suddenly fuelling another musical explosion, this time detonated in partnership with Detroit, Chicago and Dusseldorf. It was Kraftwerk’s Boing, Boom, Tschak with a South Yorkshire accent. It was Adonis’ No Way Back – but referring to a night out in Leeds rather than hedonistic oblivion. And it was Derrick May’s Strings Of Life with extra chips and curry sauce.

The original track was called Testone, which I always pronounce as ‘test tone’ – those tones are the sonic signature that give the track its character, after all. I’d read about it before I actually heard it, so my pronunciation was conjured from what I saw on the printed page – but when I did finally hear it in Warp’s record shop on Division Street, and bought a copy of my own, I realised that the remixes were punningly numbered Testtwo and Testthree. I fear that the Warp crowd may have called it ‘test one’ all along.

This version is Testfour, restructured in slightly more robust four-to-the-floor fashion by Rob Gordon. And if we were doubting the direct connection between this and the Sheffield sound of yore, the production credits make everything quite clear. Because Sweet Exorcist was the partnership of Parrot – a DJ – and Richard H. Kirk – of Cabaret Voltaire.

Repetition. Electronics. Cut-ups. And groove. Cabaret Voltaire had already met the world of dance music half way in the early 1980s, but there was a sense in which Chicago acid and Detroit techno had taken the Cabs’ experiments to their logical conclusion, and thankfully for Sheffield, Richard Kirk wasn’t going to let them have the last word. By fusing his studio knowledge with Parrot’s understanding of the local scene – Parrot had broken house music in Sheffield along with DJ partner Winston Hazel, and had charted with another Sheffield dance act called Funky Worm in 1988 – they made this track specifically for the dancefloors at Sheffield clubs like Jive Turkey and Cuba.

While never feted like the acid house fests over at the Haçienda – the Haç was a pretty special venue after all, while the Sheffield nights were movable feasts that flitted between dives like Occasions and the sumptuous splendour of the City Hall ballroom – Parrot and Winston played as crucial a role as anyone in bringing house and techno to the north of England. This scene had already budded in the late 1980s with Funky Worm, Krush’s House Arrest, FON Records and the Designers Republic. However, it was the emergence of Warp in 1989/90 that felt like the true flowering of this Sheffield talent.

Testfour isn’t the only track in this mix that represents Sheffield at the turn of that particular decade, but with those two analogue tones, it launched a locally-forged sub-genre of its own – ‘bleep techno’ – and joined the dots in all the right places between Sheffield’s past, present and future. Its mid-point breakdown is the spiritual centre of this Destroyed By Gods mix, and I mark the occasion by dropping in that “Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first send to Sheffield” sample once more, just for good measure.

Destroyed by gods indeed.

We weren’t destroyed! We were loving it!

Track eleven

Forgemasters – Track With No Name (1989)

Human League is a great name for a band. Cabaret Voltaire is a superb name for a band. I take my hat off to them both, because in the early 1980s, my chums and I realised how hard it is to fashion the perfect band name as we rotated through various semantic contortions including Abstract Plastic, Continuous Monument, and Digiphobia. So troublesome was this exercise, that we didn’t actually get round to the really crucial part of being in a band – the making of the music.

However, here we have the quintessence of a great band name, definitely my favourite within the confines of this mix. It describes the band’s sound and the roots of that sound, and pays homage to their city in three magnificent syllables:

Forge – mast – ers.

Jack hammers and furnaces; metal on metal; the rhythmic pump of machinery: if you’re looking for the secret behind the Sheffield sound, it may as well be all this as anything else. Martin Ware makes the music/industry link explicit on the Made In Sheffield documentary, and it was always the subtext to Cabaret Voltaire’s press coverage. The percussion, the pummelling, the hissing and the clattering – they sound like industry in motion, and as the archetypal northern industrial city, Sheffield’s love of atmospheric electronics has always seemed to make some kind of crazy sense.

In using the name Forgemasters, these lads made the most explicit connection yet. Forgemasters – the company – had an immense factory down in the Don Valley, and their name was emblazoned across it in stark red sans-serif lettering. From this dark satanic fortress emerged larva-flows of liquid steel, turbine shafts, ingots – even, allegedly, a ‘supergun’ destined for Iraq. Forgemasters – the band – was Rob Gordon, Winston Hazel (DJ partner of Sweet Exorcist’s Parrot), and Sean Maher. They were Sheffield techno, emotive and bass heavy, and this record – Track With No Name – was Warp Records’ first ever release.

Not that Sheffield had a monopoly on the making of this stuff. Forgemasters’ label-mates LFO and Nightmares On Wax – both of whom delivered era-defining tunes in early 1990 – were from Leeds, while Unique 3, who were originally slated to be Warp’s first signing, were from Bradford. All built their tracks bass up, and for a time – a very short time, in hindsight – this bleeping, booming noise was Yorkshire’s noise.

Well, OK. But spiritually, it was all Sheffield. Come on, admit it. Sheffield might have lacked the leisure-lifestyle infrastructure that would eventually take Leeds consumers to retail nirvana, but it still had a more sophisticated sense of how to put this gear together. It had the club (Occasions on a Saturday), the shop (Warp on Division Street), the producer (Rob Gordon), the DJs (Parrot and Winston), the designers (Designers Republic), the godfather (Richard Kirk)… in short, it had the complete package.

So in an age of ‘faceless techno bollocks’, Warp’s acts weren’t faceless at all. They had the lilac sleeve, the bulging sound, the future-retro logo, the playful graphic tricks. Here was the label that Sheffield’s early-80s scene had never had, a label with entrepreneurial nous that gave character to anonymous music, that pulled it all together and made sure it was remembered. Not that these things happen according to some well worked out plan, but Warp had learned from its immediate predecessor, FON Records, and to someone on the edge of the scene – i.e. me – Warp seemed more than a little like FON Version 2.0.

Regardless of the politics behind FON’s ultimate demise, they had brought together the talented production team of Rob Gordon and Mark Brydon – under the guise of the FON Force – along with the DJs, musicians and designers that had given Sheffield a small taste of what Manchester had with Factory. Their records were crisp, percussive and visually ultra-brite – the involvement of the Designers Republic helped give disparate tracks a coherence and shelf-presence that always turned my head.

So when FON evaporated as a shop and a label, and a lass on Radio Sheffield’s ‘youth access’ show ROTT announced a track by “a new Sheffield label called Warp”, I was hungry to know more. The track was this track – a track with no name, no less.

It’s breathy, melancholic, metallic. It could be steam-driven; it could be some kind of satanic clockwork. Either way, it drives for the future while somehow alluding to something lost, something past. For the sake of neatness and circularity, that something may as well be Sheffield’s steely glint and that awe-inspiring industrial canyon that ploughed through the city’s east end. Because in autumn 1990, just a year after I heard this track for the first time, Hadfield’s 90-acre East Hecla Works – a vast steel factory that housed one of the world’s biggest foundries – had been replaced by… Meadowhall.

A big shop.

Still. It really is a fucking good name for a band.

Track twelve

Cabaret Voltaire – Easy Life (Jive Turkey Mix) (1990)

Of course, 1989-90 is mostly remembered as Manchester’s time. They had the lot – bands, haircuts, myths and legends. And they had the venue, the Haçienda, once thought of in much the same way as the Leadmill – beery, sticky, indie – but which was, by 1989, a humid and celebrated temple to the big fish, the little fish, and the cardboard box.

Because Sheffield’s pioneering DJs and promoters never had the venues to match their dreams, they were forced to camp down in the likes of Kiki’s, Stars, and Isabella’s. These ‘nite spots’ were fraudulently ‘sophisticated’ rooms lined with chrome and mirrors and, in the case of Mona Lisa’s – later to become 1990’s firing Occasions – some none-more-1970s Penthouse-style soft porn.

One mid-1980s Sheffield night that did have something deliciously different though, was Jive Turkey. Hosted by DJs Parrot and Winston, it was a large-scale monthly housed in the City Hall’s neo-classical, subterranean ballroom, and while it helped break house music in Sheffield, it was built on a range of funk, soul and jazz styles that appealed to a latent Northern Soul spirit. Suddenly, dressed-up clubbers were travelling to Sheffield to dance with abandon – and that hadn’t happened since the dying days of talcum powder and Oxford bags.

In the mid-1980s, Sheffield City Council seemed determined to wind up anyone who might wish to be prudent with the purse strings, so in spite of recession and industrial decimation – or possibly because of those things – they spent freely on youth culture subsidies that made the blue-rinse brigade’s hair stand on end. ‘Rock on the rates’ was the tabloid-friendly, left-bashing slogan, as the council shovelled money in the direction of local recording studios and unemployment benefit gigs. Likewise, the City Hall’s status as a council-funded venue meant that Jive Turkey was effectively receiving a proportion of our parents’ income, affording the Youth Of The North the opportunity to develop excellent fleet-of-foot dancing techniques while drinking Holsten Pils.

While Jive Turkey had existed in other venues, it was the City Hall Ballroom that made it into a real event. In a 1988 Observer article about Jive Turkey, Jon Savage referred to the splendour of this “municipal showpiece”, and it truly was a show stopper in itself: 1930s’ ocean liner chic, built to impress. To either side of the main ballroom with its pillars and sprung dancefloor (the cause of disgruntlement within the local Tea Dance Posse, who complained that club nights were pulverising the parquet) were smaller wood-panelled rooms with illuminated dancefloors, in which ridiculously good dancers plied their trade, a far cry from the later dancefloor democratisation of rave – of the Haçienda, in fact.

Jive Turkey was of Sheffield, but when you were there you almost couldn’t believe you were in Sheffield. It reached such a level of authentic sophistication – not in a cocktails-and-mirrors kind of way, but in the musical sophistication of its crowd and the visual sophistication of its surroundings – that it seemed only natural that it would be once a month, and no more. In that rather ascetic day and age, a weekly Jive Turkey would have seemed almost sinful.

By the time of Cabaret Voltaire’s Easy Life, Jive Turkey had moved on from the City Hall to become a kind of floating Sheffield idea, a symbol of the city’s dance music, a less-celebrated, but much cherished answer to the Haç over there in Man… sorry, Madchester. So when Easy Life emerged accompanied by a Jive Turkey Mix, it was code for ‘Yorkshire beats on a Chicago chassis’.

You always had the feeling that, as the 1980s wore on, Cabaret Voltaire were desperate for the same dancefloor devastation that New Order had achieved under the influence of Arthur Baker, Jellybean and New York’s Funhouse club. While their own dancefloor sensibilities often seemed to leave them lurching rather than gliding, they had managed to steer a few of their most memorable 80s tracks away from the anonymity of the bar by involving producers who definitely didn’t have two left feet, including John Robie and Francois Kevorkian.

As attention shifted from New York to Chicago, Marshall Jefferson was the latest in this line of dance deities, drafted in to stop the beats stuttering and to keep the feet moving. He worked with the Cabs on their Groovy, Laidback and Nasty album, and while the languid house music may have lacked much of the punch of previous Cabs work, it served to make explicit the connections between the Chicago and Sheffield dance music hothouses.

Jefferson may have been a representative of house music’s heavenly host, but the air was thick with dissatisfaction over Groovy, Laidback and Nasty. Where was Sheffield is this pristine new sound? Where was Yorkshire? Only in one track could the city really be discerned, and that was Easy Life, which was built on the four-bleep progression from Unique 3’s The Theme that had helped give the scene its defining sound in the first place.

Scanning the Easy Life single sleeve though, Jefferson’s name has vanished from the credits, and we get a bumpier, beefier Jive Turkey sound licked into shape by the Cabs themselves, plus Rob Gordon (again) and production partner Mark Brydon. Although Mal’s vocals have gone from this version, it’s still studded with the spirit of FON studios and bleeps, and it’s a neat mix away from Sweet Exorcist and Forgemasters. In the end, it could hardly be more Sheffield, with a rattling percussive line that sounds like ballbearings in a can.

So that’s our little journey through a time when Sheffield rebuilt the bridges between its past and future musics. It should be the stuff of dance music legend of course, but in the Official History of UK House, everyone was at the Haçienda buying pills off Shaun Ryder.

Ho hum.

Time to listen to a song.

Track thirteen

Pulp – Acrylic Afternoons (1994)

Jarvis was always the master of conjuring up images of a Sheffield childhood and rendering them in terms that don’t just describe the scene, but communicate the very sense of being there. And this track is crammed with them, so you come away from it feeling sticky and sore, but a very specific stickiness and soreness derived from guzzling lemonade from a heavy, dimpled glass bottle, curtains drawn against a hot afternoon, sweating inside vividly coloured artificial fibres, an indolent sense of drift sapping any urge you might have to play out, the flickerings of Farmhouse Kitchen almost hidden beneath a sun-bright layer of screen dust.

Not that this song specifically describes that situation, but with his eloquent imagery, Jarvis introduces the concept of the ‘acrylic afternoon’, with its ‘lemonade light’ and everlasting sense of creeping ennui. In his case, inevitably, there are sexual undercurrents. In my case there was impending salad, and Pek chopped pork, and Instant Whip, and a night under a single sheet, reading comics because there was no dark.

Whatever went on in your own acrylic afternoons, Sheffield summers were full of them.

“Julia, Diane, Heather, Rachel, come home…”

Home for your tea.

Track fourteen

The Box – Big Slam (1984)

For a while, I had a thing for The Box. They had some of the rawness and funk I’d come to expect from a certain strand of Sheffield music, but this rawness was live, squawking, eccentric and strange. Not synthetic. Not robo-grooved. Not disco, not pop.

Formed from fragments of Clock DVA (who maybe should be on this mix, but who don’t really mean much to me, so… well, it’s my chuffing mix, orreyt?!), The Box tethered a freeform jazz spirit to a swinging lump hammer and knocked chunks off the walls of Babylon. Their sound hung off a searing sax, wielded by noted Sheffield beard-wearer Charlie Collins, and they were somehow – well, mostly – ring mastered by a yelping front man called Pete Hope.

Now.

You see.

While I affect to have been at the heart of this scene, I was a mere bystander and simply observed most of this stuff from an attic bedroom off Carterknowle Road. This fact becomes clear when you realise I didn’t really know The Box, had never seen them, and in fact knew nothing about them until the parent of a child at the nursery school where my mum worked offered us a couple of kittens.

R-r-r-r-r-right….

No, hold on. Y’see, that parent was Pete Hope, and in the context of Birley Nursery School – blue collar, tightly-knit, not-exactly-deprived-but-not-exactly-rolling-in-cash Birley – his bald-with-vividly-coloured-tuft hair style was… well, I’m sure it didn’t go unnoticed.

Pete Hope offered my mum the kittens, and we took them, and named them after his children, the ones who went to the nursery. So one kitten was Cally. The other was Jay. And they lived with us for years and years and years.

But because our kittens’ dad was the singer with The Box, who made records and everything, I found myself lapping up their sound for a little while, and that’s why they make their jarring contribution to this mix: torn fragments, shredded sax lines, strained vox and breathless attempts to get somewhere… anywhere… up, up, up…

As the Designers Republic made their first assault on Sheffield’s graphics/music interface – in tandem with Leeds band Age Of Chance, it has to be said – they seemed to usher in, or at least popularise to a degree, an age of shouty slogans, sub-graffito clamour and statements smartly-dressed: ‘Release the Heat’; ‘You Can Live Forever’; ‘Work Buy Consume Die’. The very phrase ‘Big Slam’ seemed to share precisely this emotional punch, and whatever it meant, it sounded very there and then.

So. Je-jaannng. Now we’ll. Whump-KLAAANG. Listen to more. KANG-dnnnn. Jaggedy noise with. HAAWWNK. Lyrics like slogans. Cha-ching.

Track fifteen

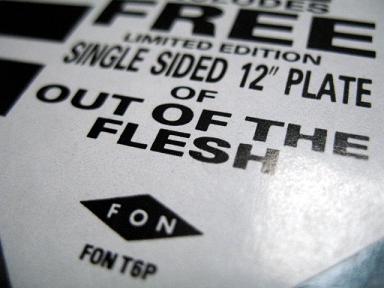

Chakk – Out Of The Flesh (1984)

You wouldn’t believe how much I longed to love this band, just because they so rigidly adhered to every clause of my self-penned Sheffield music manifesto – you know, the one that existed only in my head, but felt like the word of Vulcan himself.

I longed to love them long before I heard them, and when I did finally submit to their aural kicking, I made myself like them. Honestly. I just listened and listened and made myself submit to their wayward clang, and while that may sound… erm… pathetic, their sleeves were too good, their name was too perfect, their wholesale devotion to the Sheffield music template (my Sheffield music template that is. Not available in the shops) was too obvious for me not to enjoy their actual sound.

Looked at objectively and with hindsight, they were neither funky enough, nor electronic enough. They didn’t have enough bass, and they didn’t have enough groove. But I’m not talking objectivity here. I’m talking:

i) Incendiary Designers Republic sleeves

Out Of The Flesh pre-dates the Designers Republic by a couple of years, but once they were up and running, Chakk were one of their first pet projects. With blocky constructivist graphics and hail-the-revolution slogans, they developed a visual style that leapt off the 12″ square of cardboard even as you held it in your hand. It was a look that you knew came from Sheffield – it was just a cut and a paste away from DR’s other partners in graphical terrorism, Age Of Chance and Pop Will Eat Itself – and it had that now-notorious Republic mystique, and you wanted to own it, and be part of it. And to like the record within. It wasn’t just a slab of vinyl: it was an event.

ii) A pioneering Sheffield label

Chakk were on FON. In fact, in many ways, Chakk were FON. And when they rode a hype-wave to the land of the major label – MCA were the ones clutching the cheque book and pen – they swiped a famously hefty advance and sunk it all into FON studios, another Sheffield music institution. They never made it big mind you, and MCA dumped them fast, but that pile of cash remains a part of Sheffield music folklore. FON turned out to be more talk than action, and by 1989 they were on the verge of evaporation, but their blazed trail gave Warp an easier toddle through the musical jungle than might otherwise have been the case. For services to Sheffield music, I salute them.

iii) Mark Brydon

Brydon was Chakk’s bass player, but before long he was so much more. One half of the FON Force production duo alongside Rob Gordon, he flicked the switches and slid the faders on some significant Brit house music – House Arrest by Krush was one such, and as should by now be almost tediously predictable, that too proclaimed its brash presence with a DR sleeve forged from some unholy nuclear fission involving cycling shirts, elongated typefaces and a no-doubt illegally blagged Mercedes logo. Like Rob Gordon, Brydon seemed to have a finger in almost every Sheffield musical pie – and that made Chakk essential, whatever they actually sounded like.

iv) A noise that could have come from nowhere else

Looking back now, it all seems too self-consciously Sheffield – that much is obvious as I write these notes. The jarring groove, the sonic stabs, the tape loops/samples, the cooling-tower grandeur and the girder-like dancefloor stance. Out Of The Flesh has one hook of note – a piercing Jake Harries-warble that goes “Ooooh oo-eee-ooooo ooooh” – and the rest resembles seven different records all being played at once. But it had to be attempted, and in 1984, it could have been the way forward.

As could Lionel Richie, George Michael, or Black Lace.

And I’d take Chakk over that shit any year.

Track sixteen

ABC – All Of My Heart (1982)

Sheffield’s heart is not beautiful, as I one day learned to admit. Not in conventional ways, anyhow. But step beyond the city centre and you discover wooded hills, stoney hideaways, a non-conformist grandeur that sits and sulks and sighs, and is “not fussed” about much. It just gets on with being great.

And just as the city’s brutal concrete is evocative of an era rather than being conventionally gorgeous, so the Sheffield sound hasn’t always been known for its chiming sense of melody. The rusting slabs of industrial funk conjure up a musical past that did make a difference, but sometimes, that really isn’t enough. Because right now, after The Box, and Chakk, and hypnotic drum machine workouts, don’t you yearn for something orchestral and sumptuous? Something with a little grit, yes, but grit that’s carried along on a delicious, crashing wave of emotion? Don’t you want the aural equivalent of those hills, those valleys, those acres of green?

Ah, bless. Sounds like it’s time for ABC. Sounds like it’s time for…

All Of My Heart.

From robo-grooves to devastating soul. It’s a journey we had to take, and it’s the journey that ABC made too. Once they were the whirring, buzzing, synthetic, electronic Vice Versa. Then they shut themselves away, self-consciously absorbed the city’s sense of being in the gutter looking at stars, dressed up in gold, and drenched the world in bitter-sweet tears. No longer Vice Versa, now they were ABC, and with Trevor Horn producing, they gave us a song as great as any I’ve ever heard.

All Of My Heart.

It sings, it shimmers, it soars. There are raindrops and puddles, and heels and bright lights. There are mascara streaks and tears barely suppressed. Tumbling pianos, tornadoes of pain. And as it ends, and you think it just might soar once more, it’s gone.

It’s gone like a cab in the night.

Track seventeen

Human League – Love Action (1981)

Everyone knows Sheffield was about rhythm, and clunk, and the spirit of Eno-era Roxy. But Sheffield was also about – is also about – stories well told by poets who do pop. Which brings us right back to the Human League, post-split; they should have vanished without a trace, but instead they did make-up, synthesisers and recession-scarred urban glamour better than anyone, before or since. Certainly, Martin Ware and Ian Craig-Marsh must have felt… well, let’s not go there.

Irresistibly syncopated and with a jewel-like sheen, Love Action is the very best place to hear Phil doing his half sung, half spoken-word thing – a little out of tune and a little bit earnest, but so bruisingly honest it tears at your heart. Caress a 7″ slab of this and you’re holding crystallised time; it’s 1981 in all its strappy, eye-linered, Tory-baiting, three-channelled, asymmetric glory.

Track eighteen

All Seeing I – The Gods And Sheffield (1999)

And finally… a rewind for The Gods And Sheffield, the track that gave us our intro eighteen tracks ago.

“Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first send to Sheffield.”

Well, if that’s true, at least they get a bloody good soundtrack.

Destroyed By Gods is a compilation mix created by me for my own listening pleasure. This discussion of the mix highlights some of my feelings about music from the city I grew up in; if you wish to comment on the article, please feel free to drop me a line via the Contact page on this website.

The Destroyed By Gods mix is available to listen to or download here. Alternatively, listen using the Mixcloud widget at the top of this page.

And finally, now you’ve emerged unscathed from the ‘Destroyed By Gods’ experience, why not explore Noise Heat Power’s Brain Aided Dancing – a mix in praise of the MIGHTY! Designers Republic?

Recommended books:

Beats Working For A Living by Martin Lilleker.

Rip It Up And Start Again by Simon Reynolds.

Warp by Rob Young.

Truth And Beauty – the story of Pulp by Mark Sturdy.

Industrial Evolution – through the eighties with Cabaret Voltaire by Mick Fish.

Recommended DVD:

Made In Sheffield directed by Eve Wood.

Text © Damon Fairclough 2006

Images © Damon Fairclough 2007

Share this article

Follow me