For the Lyceum with love: a history of Sheffield Lyceum Theatre

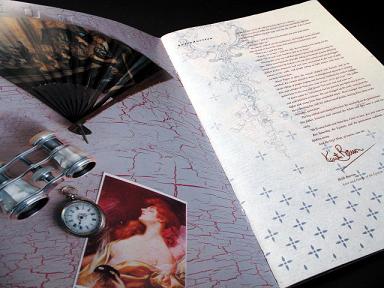

When Sheffield’s long-derelict Lyceum Theatre was reborn in 1990, and I found myself writing its history for publication in a book, I felt I was composing a love letter to someone I was far too young to have known.

Sheffield, 1990: I was sweat-drenched, pale and twitching. The rattle of a 909 snare drum propelled me through many a weekend. I was hypnotised by rhythm and besotted with the sound of the city; and in 1990 that meant test tones, circuit-board bleeps, and gut-purging, keck-messing bass.

But lest I forget, I did more than dance my way through that year.

I was young-ish, being fresh out of polytechnic, and the tribal rites of my Saturday nights were important; but no less enjoyable were the sedate and sedentary days I spent rummaging through old theatre programmes, boxes of photos, and pages and pages of musty memories. Flung by fluke into a writing project I could only have dreamt of a year before, I found myself working with a friend on a book about the Lyceum Theatre, Sheffield. It was a city no-man’s-landmark, a Victorian confection that had been derelict for so long it had become almost invisible. It had closed as a theatre when I was two; it survived as a bingo hall for a while, as was the way in the 1970s, but it seemed destined to become one of those inner city puzzles whose solution lay in a big thump from a wrecking ball.

Now though, the Lyceum was being transformed. A massive renovation project saw the backstage areas demolished, replanned and rebuilt; the auditorium gutted and carefully pieced back together; and new public foyers, bars and hospitality suites attached. The Lyceum Theatre Appeal commissioned a book to celebrate its reopening; my friend James Richardson and I were the people charged with bringing this book to fruition.

It was an amazing job to take on in that easily-lost year after graduation. We worked instinctively, writing to all the actors we could think of who may have trodden the Lyceum boards; we wound our way through roll after roll of microfilm; we visited as many people as we could track down who had memories to share; and we dived headlong into archives to see what we could find.

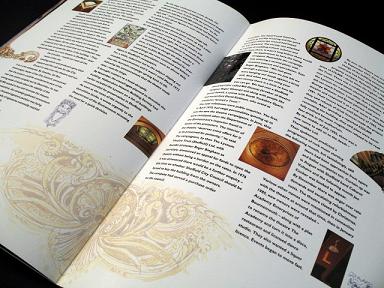

We marshalled our material and I turned it into a whimsical piece of writing about the theatre’s long rise and precipitous fall – from 1897 to 1969. Local journalist Alan Powell added an article about the seemingly hopeless campaign to save the building from demolition and reopen it as a working theatre. Photographer Laurance Richardson contributed some magnificent images, including a memorable shot of bulldozers digging out the auditorium floor. And the whole thing was given a sumptuous gloss by the Barnes Design Partnership.

The book was launched alongside the resplendent Lyceum Theatre in December 1990. However, while I’m sure the odd copy still floats round the city, I believe that it has now all but vanished. So here instead are the words I wrote; my history of the Sheffield Lyceum, as gentle a piece of theatrical reminiscence as you’ll find anywhere. But it was 1990, and I was 23; so when I finished it, I probably danced to pummelling techno for two days solid.

Great times, eh?

—

A brief history of the Lyceum Theatre, Sheffield

They first ate chocolates here in October 1897, rustling papers and swallowing sweets so they could cheer the triumph of the architect who had built such a place for Sheffield. From the gods, to the stalls, to the centre of the dress circle where the Master Cutler sat and watched, they sang the National Anthem together before settling down to the Carl Rosa Opera Company’s Carmen. As the third act closed and the curtain fell, they clamoured for John Hart, the theatre’s managing director, to take the stage.

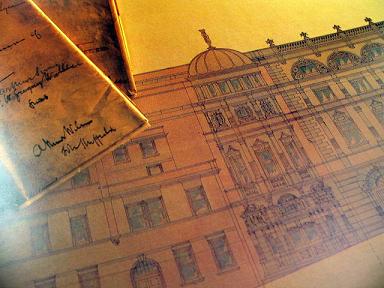

He accepted the invitation, and told his audience that people had mocked the idea of a first-class theatre in Sheffield, but the magnificent turn-out proved that it would be a great success, a statement that was greeted by generous applause. He read out a telegram from Sir Henry Irving, the finest actor of the day, who sent them “truest and heartiest good wishes for the success and prosperity of the new Lyceum Theatre,” a message which was greeted with cheers. He then claimed that the magnificent architecture ranked with the best in the country as there was a superb, clear view of the stage from every part of the house. Again, the crowds clapped, the loudest acclamation coming from the very top of the perilously steep gods. This celebration of the glorious building provided Mr. Hart with the opportunity to introduce W.G.R. Sprague, one of the nation’s finest theatre architects, who gave a nervous bow before leaving the stage to cries of “Speech!”. He declined to comment on the occasion but the applause forced him back in front of the curtain once more to bow his thanks.

—

“Well within the recollection of the proverbial oldest inhabitant, Sheffield was a town in which the drama flourished not,” said the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent when it greeted the opening of the Lyceum. The building of a new Sprague theatre in the city, however, provided further evidence in their view that “any reflection which an artiste’s mind might have cast on Sheffield in the past has now been removed.” Here was a building worthy of the best, and there was every confidence that the best would come. It also surrounded the audience with a splendour that many were not at all used to, although Victorian class distinctions divided the patrons of the theatre in various unsubtle ways.

Inhabitants of the stalls and dress circle were welcomed in through plush foyers while those heading for the gallery, or ‘gods’ as it was known, were relegated to a separate entrance round the corner. Consequently, although everyone who attended the Lyceum’s first night was evidently impressed by the beautiful auditorium, some were no doubt more impressed than others. Social protocol dictated that whereas the area round the dress circle was a mass of intricate plasterwork, delicate paintings and luxuriously upholstered seats, the gallery was devoid of decoration and the audience was obliged to sit on stone steps with a thin cushion attached. Nevertheless, the colour scheme of cream and gilt made for an exceptionally fine theatre, the ceiling featuring a series of floral paintings, and the front of the circle, balcony and the bow-fronted boxes being enlivened by lively plasterwork.

Perhaps the most striking effect, however, was provided by the proscenium itself. This was decorated along the top by huge curls and swirls of gold which reached well down the sides of the arch. The vivid red of the curtain was clearly visible through the spaces in the design, making a spectacular frame for the first-class companies expected to play on its stage. The Sheffield Weekly Independent was in no doubt that it was a great cause for celebration in the city. “There was only one opinion on Monday about the new Lyceum Theatre. It is beautifully decorated, brilliantly lighted, one can hear in it perfectly, and everybody can see the stage.” But in those days before central heating when a trip to see a play was for many an escape from austere, cold surroundings, there were other considerations too. “The new theatre is also warm,” it said, “when doors are not unnecessarily left open.”

—

Four years earlier, an architect called Walter Emden had designed the City Theatre, a rather plain building which occupied a site on the corner of Tudor Street and Arundel Street in the centre of Sheffield. It had once been the garden of a nearby house, and subsequent buildings established it as a place for entertainment, although of a rather different nature to that which the Lyceum would aspire. First there was a popular circus, a flimsy wooden structure which was let to a man called Dan Leno and which was known as Leno’s Varieties. When a showman called Alexander Stacey took over in 1890 it became known as Stacey’s Circus, carrying on very much as it had done before, until Mr. Stacey’s interest in dramatic art caused him to change his policy. The name was changed to Stacey’s Theatre and plays were performed there until, in 1893, a show called ‘On The Frontier’ required a fire to be lit on stage. Rather inevitably, the fire spread and the wooden building burned to the ground.

In its place, Stacey built the City Theatre which he ran for three years, but by the end of 1896 he had not been able to make it as successful as he had hoped and the Sheffield Local Register for December 3rd records “City Theatre purchased by a syndicate who decided to make structural alterations and call the house the Lyceum.” This is indeed what happened. The theatre opened under its new name for a short run from January 1897 until Easter, but then closed to allow rebuilding in accordance with W.G.R. Sprague’s grand designs.

Sprague himself had served for three years in the offices of Walter Emden, the City Theatre’s architect, having already done four years in the service of Frank Matcham who designed another great theatre, the Sheffield Empire of Charles Street. For years afterwards, the distinction between the two divided the city into those who favoured variety at the Empire and those who preferred the up-market atmosphere of the Lyceum where usherettes were known as theatre attendants, boxes of chocolates were sold in preference to Mars Bars, and Shakespeare featured more often than acts like ‘Douglas Maynard and his Xylophone’.

“I shall do my best,” said John Hart only a few months before the new Lyceum opened, “to produce Shakespeare whenever practicable. I feel certain that if we prove that Shakespearian plays can be properly produced, and that our house will accommodate the requisite number of people, I shall have no difficulty in inducing Sir Henry Irving to pay us a visit.”

On Monday October 18th, exactly a week after the theatre’s opening, Sir Henry arrived with Ellen Terry and his London Lyceum Company to perform The Merchant of Venice. He was to become a regular performer on the Lyceum stage, and it was at the theatre that he opened his farewell tour in 1905. The company played a week in Sheffield during which time the Lord Mayor gave a luncheon in the actor’s honour, and Irving said of himself that he was a man “the sands of whose life are running fast.” The local press commented on the farewell speech he gave from the Lyceum stage once the final night’s performance was over.

“The great actor appeared deeply moved and uttered his speech in a voice which was, at times, almost choked with emotion.” He went on to say “I would like to thank tonight many citizens of Sheffield, many distinguished citizens for their sweet acts and most gracious courtesies… I hope that you will always remember me as your grateful, loving and loyal subject.” Less than a week later Sir Henry Irving died, but the Lyceum, of course, lived on.

The stage beneath its ornately gilded proscenium arch played host to some of the finest actors and companies of the time including Sir Thomas Beecham’s Opera Company, which was made up of over two hundred artistes, and on July 14th 1904, the great Sarah Bernhardt gave one performance of La Dame Aux Camelias. Such was John Hart’s determination to provide quality productions that he seldom put on the music hall acts which could fill other Sheffield theatres. Even when he booked light humorous shows, he still insisted that “refined wit is better than what is known as ‘knockabout comedy’. We shall bring society plays and comedies here and pantomime will be a great feature with us.”

—

Things could have been very different. Fire had always been a hazard in the theatre – the 160-year-old Theatre Royal which stood across the road was completely gutted by flames in 1935 – but the Lyceum managed to shrug off its own serious outbreak in 1899. At around half past five in the afternoon of November 6th, a blazing fire was discovered on the stage where a play about the Boer War, Soldiers of the Queen, was due to be performed, and many people seemed to treat the subsequent events as a theatrical experience which, for once, would cost them nothing. According to press reports, “The cry ‘the Lyceum is on fire’, which rang through the streets, brought thousands of spectators to the spot.” The Sheffield Telegraph was sure that the play’s opening scene “with all its spectacular effects, could not have afforded anything so brilliant as was at this time to be witnessed from the auditorium. The whole depth of the stage, from the footlights backward, was full of fire. At intervals the brilliancy of the spectacle would be enhanced by a gas flame shooting out.”

It was certainly a tragic occasion in terms of financial loss – ten thousand pounds’ worth of damage was caused which included the destruction of all the scenery for the coming pantomime, and Mr. Preston, the director of the company touring Soldiers of the Queen, lamented that none of his scenery or effects was insured. No one was hurt however, and many members of the Sheffield public evidently welcomed the opportunity of watching another good bonfire so soon after Guy Fawkes’ night. “The number of sparks that flew about was amazing,” commented one journalist, “but although these showers were very fine, the spectators wanted something besides sparks… To see the ruddy flame filling up the whole of the window space, with no smoke to obscure it, was a much finer sight than can be seen at many fires, even those on a similar scale.” Not only had the Lyceum defeated one of theatre’s greatest enemies, but it had given the city yet another wonderful show into the bargain.

—

The Lyceum was destined to become one of the country’s great pantomime houses, although there was no traditional three-month show at the theatre for a number of years following its opening. John Hart ran a chain of theatres which included the Grand Theatre in Leeds, the Opera House in Bradford and the Prince’s Theatre in Manchester, and it was not long before Sheffield’s Theatre Royal also came under his control. The Theatre Royal, one of the oldest theatres outside London, stood on the opposite side of Tudor Street to the Lyceum, and had played traditional variety style pantomime for many years. Consequently, John Hart kept the big panto there while the Lyceum hosted smaller family shows like Little Bo Peep or comic operas like Tom Jones which stayed for only one or two weeks over Christmas.

It was not until the early 1930s that the large scale pantomimes produced by great impresarios such as Emile Littler and Francis Laidler moved into the Lyceum on an annual basis, and only after the Theatre Royal was destroyed by fire in 1935 did its reputation as a natural home of pantomime begin to grow. The stage may have been a little too narrow for the most lavish operas and ballets but for panto, its tall arch, decorated with golden rococo scrolls, was to provide an ideal picture-book setting for real spectaculars. Families from Sheffield and beyond would pack the theatre twice a day for three months of every year, usually beginning on Christmas Eve and playing right up until Easter.

For thousands of people in the city, the trip to the Lyceum pantomime was an exhilarating introduction to the theatre. Parents and children would sit in the warmth of the gold and crimson interior chatting excitedly, listening to the orchestra tuning up, and passing the time before the show by reading the large advertising curtain. This filled the proscenium opening with names like Davy’s Pure Ices (“The best you can buy – as served in this theatre”), the Gwen Wilken School of Dancing (“For correct training in all branches of the Art”), and White, Favell and Cockayne (“Sole agents for the ‘Meriel’ cigars as supplied to the House of Lords”). It was designed by Stillwell Derby of Nottingham who made sure it was not out of place in the grand surroundings by decorating the space between the announcements with intricately painted patterns. Eventually the red front curtain would drop, the orchestra would play the overture, and hush would descend over the audience as they lost themselves in two hours of Aladdin, Cinderella, or Babes in the Wood.

However, even with the pantomime, the Lyceum was determined to prove itself to be a better class of theatre. The shows which the great producers brought were not just a string of variety turns – they stuck to the story and most of their players were chosen from either revues or musical comedies that had visited during the year. Performers who had played at the theatre in The Desert Song or The Maid of the Mountains would be retained for the pantomime, and consequently, the Lyceum did not boast the big star names who appeared at other venues. Indeed, those names that did appear were never more important than the plot. The show wasn’t halted so that a comedian could do his usual act – everything had its place within the story, and the story always came first.

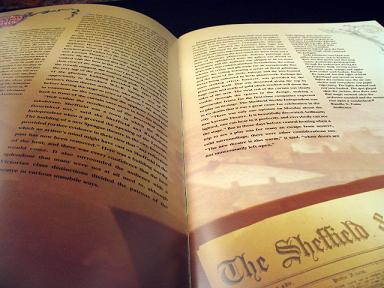

In the 1940s, this policy changed when a man called John Beaumont took over the position of managing director and decided to put on his own pantomimes rather than those of other producers. Big names who were doing well on the radio began to star in the shows – people like Frankie Howerd, Freddie Sales and Harry Secombe – and in 1948, John Beaumont hired a highly successful variety comic called Frank Randle to appear in Mother Goose. The story no longer reigned supreme in Lyceum pantomime as the press were quick to point out: “Officially, in this Sheffield Lyceum pantomime, Frank is Jack, but I have yet to discover what Frank is to the plot, or to recall an utterance of his that had anything to do with it.”

Frank Randle was widely loved on the variety circuit, but he was also notoriously unpredictable, frequently performing while drunk. It is not hard to imagine how some parents probably felt, taking their children along to see his routines which involved belching and liberally swigging Guinness. Then again, the children themselves probably loved every minute.

Four years later, when Ken Platt appeared with Morecambe and Wise in Dick Whittington, the press seemed even more incredulous: “One is left wondering how long it will be before all pretence at story vanishes from pantomime, for in this Dick Whittington there is even less plot than usual.” Nevertheless, pantomime at the Lyceum became a great Sheffield institution and winter just wouldn’t have been the same without it.

—

So the Lyceum managed to survive three months of over-excited, noisy kids with sticky fingers putting their feet on the seats. If it could get through that each year, perhaps it was to be expected that it would cope with a World War or two. The citizens of Sheffield did their best to cope too as large sections of the male population disappeared overseas and theatre programmes had to stress that actors were not shirking their responsibility to the nation. “All the male members of Peg O’ My Heart have either attested or are not eligible for the navy or army,” they said, and every effort was made to maintain theatregoing as a regular habit, despite the upheavals in Europe.

Theatre enabled people to forget their troubles for a while as they lost themselves in musical comedies or light opera, and there were also plenty of specially written pieces designed to strengthen the public spirit against the enemy. There was London Pride in 1917, “the war play which drew all London to Wyndham’s Theatre for nearly nine months,” and in May 1916, the Lyceum was transformed from a theatre into a cinema to show the official propaganda film Britain Prepared whose scenes of munitions workers and British troops were greeted with loud applause.

Three months later, the Lyceum was again used as a cinema to house D.W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation. Although the subject matter may not have appeared directly relevant to war-weary Sheffield – it dealt with the American Civil War and the creation of the United States – the Lyceum’s patrons were reminded that “the vital and enormous part which women played during those years is being, and will be duplicated by the heroic women of the UK.” This massive production required far more than the jaunty piano accompaniment which was usual in the silent cinema. It had a full orchestral score and boasted that with the help of the camera, it could “put upon the stage 18,000 people, 5,000 horses, and 3,000 scenes,” much more than even the grandest pantomime could achieve.

Even the act of going to the theatre was cited as an aid to the war effort. Every programme carried the notice “by visiting this theatre and paying the Government Amusement Tax you are helping Great Britain to win the war.” By 1939, rather more ominous warnings were included reflecting the newer dangers of the Second World War, but despite the threat of bombing, the Lyceum was determined to see the conflict through: “Unless we are instructed to do so, we shall not clear the theatre during any performance, we shall carry on.” In case anyone was disturbed by the idea of watching the Court Players or Sadlers Wells Ballet or Noël Coward in Present Laughter while Sheffield burned around them, the Lyceum advised them “You have nothing to lose but everything to gain by taking your troubles as lightly as possible. Stand up! Cheer up! God save the King.”

Britain Prepared and The Birth of a Nation were not the only films to be shown at the Lyceum. In July 1913, a series of short films produced by an early colour process known as Kinemacolour ran for a fortnight. Audiences were impressed, but one commentator couldn’t help wondering whether places such as the Lyceum may not have met their match. “The Kinemacolour,” he said, “is evidently going to be a serious competitor with the dramatic art.” In the event, it was far too early for moving pictures to be dealing death blows to live entertainment, but warnings about future developments were already being sounded: “It is impossible to ignore the in-road that is being made from many points upon the legitimate activities of the theatre.”

—

One group of people determined to make sure that the theatre’s legitimate activities carried on were the amateur companies such as the Sheffield Teachers or the Elmsdale Operatic Society who always found a welcome home in the Lyceum. They seemed quite content to live up to the theatre’s required standards, usually producing lavish souvenir programmes that were actually far grander than the rather plain ones which accompanied the professional shows. The amateurs would fill the pages with photographs of the leading players in costume, carefully posed in scenes from the show, often with as many characters as possible crammed into the background. The big spectacular shows continued to come too, such as the production of Ben Hur which required an apron stage to be built round the orchestra pit to accommodate the chariot racing. One night a chariot came off the track but with shows like this, the Lyceum’s reputation as the home of high quality theatre was unharmed.

It was further enhanced by the visit for several years running of the official Walt Disney stage production of his animated film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The show boasted a cast of sixty, 23 scenes, real dwarfs and truly magical stage effects. It seemed there was no spectacular show that the Lyceum could not house, and in the attempt to stress that it was quality that made the theatre superior to its rivals, the management would claim literary credentials for plays that were rarely more than ordinary. Astonishing hyperbole would accompany a production’s advance publicity: referring to a 1925 show called The Man with a Load of Mischief by Ashley Dukes, the programme screamed that it had been “received on its production with unanimous praise from press and public as being the play of the century and worthy to rank with the classic works of Sheridan, Goldsmith, and Congreve.”

Perhaps mindful of their own motto however – “The drama’s laws the drama’s patrons give, for those who live to please must please to live” – the 1930s saw the staging of popular variety shows alongside the usual fare of Carl Rosa, D’Oyly Carte, and Sadlers Wells. The Lyceum even went one better than the Empire where variety was most definitely the spice of life, by hosting the first variety radio broadcast ever given from Sheffield. Its success was noted in the Daily Independent: “About two thousand people took part in last night’s broadcast and not a few people punctuated the tumultuous applause with shrill whistles.” Perhaps the sight of the single microphone slung above the stage encouraged them to make as much noise as they could, not knowing of course that it “had only been placed there to insure clearness in broadcasting the ventriloquist.” The article fails to mention whether or not it picked up the sound of his lips moving.

—

As time passed though, the theatre which had lived through fires and bombs, children and chariots, was to come up against the more resilient opposition offered by television. Even the mighty Empire which had jostled for position with the Lyceum over many years was bulldozed to the ground in 1959. There was less money to spend on the lavish spectaculars and cheaper ways of filling the seats had to be found.

So the Lyceum became home for twenty-six weeks each year for Harry Hanson’s Court Players who produced twice nightly repertory theatre, changing their plays week by week. They performed broad north country comedies and shows with vaguely risqué titles such as My Wife’s Lodger and The Man Who Couldn’t Quite, interspersed every now and then with a genuine classic such as A Streetcar Named Desire.

Harry Hanson himself liked to give a personal endorsement guaranteeing the quality of the coming production, expressed in his own enthusiastic style. He would assure the public that his company was so thrilling “that it was a common occurrence to find some of the people so worked up that they had to leave the theatre for a while to regain their composure.” He also stressed that while he would never underestimate the intelligence of the Court Players’ audience, he was not in favour of producing “Ibsen, Chekhov, Pirandello, or any ‘Highbrow Dramatist’ which theatre goers of extremist views might wish to see.”

The Court Players kept the theatre going through the summer with their vast repertoire of plays and two seats for the price of one on a Monday night. However, with the coming of the 1960s, John Beaumont found that the lack of suitable productions during the summer and the vastly reduced audiences were forcing the theatre to take a two month ‘vacation’. Various attempts were made to make the theatre pay, such as putting bingo onto the stage that had been graced by white horses and chariot races and the feet of Sir Henry Irving, but it was evident by now that the Lyceum was finding the modern world a rather alien environment. The inscription on its programmes read “A city without a theatre is like a lamp without a light”, and the light that was the Lyceum was starting to dim.

—

Sheffield had been blessed with a theatrical beauty. A paper called The Era welcomed its birth in 1897 with the comment “Mr Sprague would have the temple of histrionic art imposing to the passer-by. He thinks that among the architectural beauties of a city the theatre should be prominent, and should, moreover, have a particular character.” By March 1969 however, histrionic art had passed the Lyceum by. It became a temple only to bingo and dry rot as the echoes of the rustling sweet papers began to fade, and the planners and the councillors squabbled over the land it stood on. The chocolates were taken across the road to a new theatre, the Crucible, and the Lyceum could only stand and wait to be done up or knocked down – waiting for someone, somewhere, to finally make up their mind.

From The Lyceum Theatre Book, researched and edited by Damon Fairclough and James Richardson, 1990. If you’d like a copy… good luck.

More writing about theatre on Noise Heat Power:

An argument in concrete – A personal history of the Crucible Theatre

The Crucible method – Forty years of the Sheffield Crucible

Dedicated to discomfort – A personal history of the Liverpool Everyman

Text © Damon Fairclough 1990, 2007

Images © Damon Fairclough 2007

Photographs in ‘The Lyceum Theatre Book’ taken by Laurance Richardson

Share this article

Follow me