No idlers, no rioters: words and sounds created at Bill Drummond’s Curfew Tower

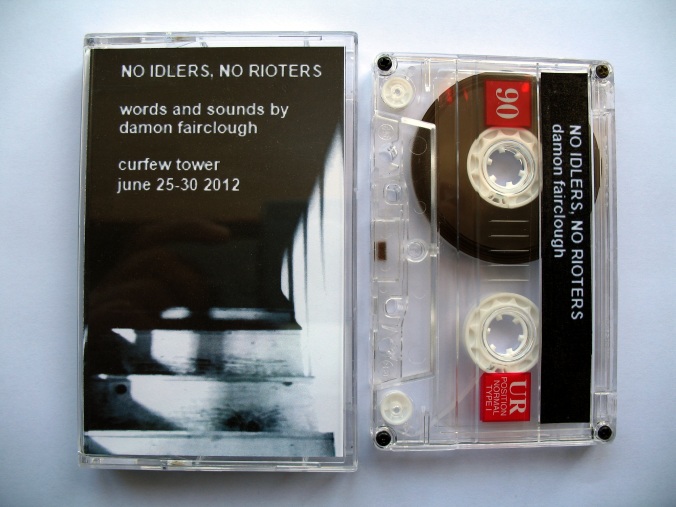

In June 2012 I travelled to the Curfew Tower in Cushendall, County Antrim, on a mission to spend a week as artist-in-residence at this 195-year-old stone prison. I’d been briefed to produce an audio cassette inspired by my stay, which I did. And here it is, now rendered internet-friendly, as a sound file and as a body of text.

Before we begin: a little context.

No Idlers, No Rioters began life as a piece of writing produced while I was resident artist at the Curfew Tower in Cushendall. I then recorded it as a spoken word piece, with added sounds and atmospheres, using a Tascam Portastudio that was also resident in the tower. This was the purpose of the mission after all: to deliver a completed audio cassette back to the project’s curator at Static Gallery in Liverpool.

Both the audio and text versions are included below, and while the audio is essentially a reading of the text, I would add that there are a couple of extra sonic surprises that might make it worth a listen. Though I’ll let you be the judge of that.

A year after the piece was originally created, it joined all the other tower cassettes in becoming part of an audio collage produced by Static Gallery to mark the end of their tower curatorship. This collage received a limited edition vinyl release in summer 2013, with the following contributing artists: Ex-Easter Island Head, Alan Dunn, Sophie Coyle, Jeff Young and Martin Heslop, Easterjack, Singersongwriter, Pointfive, Jinx Lennon, Clinic, Daniel Simpkins and Penny Whitehead, Liam O’Callaghan, Paul Sullivan, Bill Drummond as Tenzing Scott Brown, Paul Simpson… and me.

Finally, I performed the piece with musical backing from Ade and Hartley of Clinic – a hypnotic bongos/harmonica/guitar rumble – at the Curfew Tower mini-festival on 7 August 2013: the imagined spirits raised on that night will live long in my memory.

That’s it for the context; now on to No Idlers, No Rioters itself. However, if you’re still intrigued about the tower or how come I came to be there, please head over to the full story in an article called The House of King Boy D.

—

No idlers, no rioters

Words and sounds by Damon Fairclough created at the Curfew Tower, 25-30 June 2012

My name is Damon Fairclough, the rather ambitiously-named artist-in-residence at the Curfew Tower, and I wish I believed in ghosts.

I wish this tower, with its creaks and its dungeon and its corners thick with dust – I wish it contained more than just books and CDs and deodorant and duvets, and instructions about when to put out the bin.

I wish I could climb this tower and see wisps and shimmers in the shadows, and know – I mean really know – that I was passing through a veil of spirits, breaking the temporal skin that grows between us and the layers of the past.

Because if I believed in ghosts, and could sense their comings and goings, and feel their gaze on the back of my neck, and catch the twist of the air as they raced from my sight… then I’d have a story to tell. I would be more than just a man alone in a tower; I would be both a receiver and transmitter of messages; and while that’s a description that might also apply to a postman, I think the involvement of the deceased would lift my situation out of the ordinary.

But I’ve never seen a ghost; and even if I did, I would never believe it was there. I know there are people who would enter a place like this and swear blind they could feel a mystic chill – “It’s so cold in here,” they would gasp; “Can’t you feel it? The dead are always with us, always watching…”, and I would maybe nod a little – just enough to remain polite – while thinking yes indeed it is cold in this 195-year-old stone tower, as sturdy and thick as Geoff Capes’ fore-arm, but you know, if you go upstairs to the living room with its three lovely radiators, it’s as cosy as Christmas up there.

The dead are always with us indeed.

In your mind they are, which might be a comfort; but it’s no more the truth than “I’m getting a Maggie coming through… Maggie anyone?… Or… it could be Mabel.”

The funny thing is – the contradictory thing is – that I’ve often pretended to be able to pick up the energies of history, to imply that I’m sensitive to vibrations within the fabric of the moment – vibrations of past lives I mean. Not spooks; not “Whoooo, I am the ghost of Christmas 1974” or any of that Shiver & Shake stuff; but a kind of embedment that I pretend occurs when people spill their hopes and fears and they soak into their environment, and if you’re willing to open your eyes and ears to the babble, you’ll feel yourself traverse the borders of the past.

I talk about it in relation to Sheffield, to Liverpool; to places whose intimate corners I’ve overlaid with excitements of my own. And thus I have a sense that I’ve added to the bubbling of energy, and by revisiting these places I feel the seductive prickle of fleeting lives.

But I expect it to happen; I want it to happen; so I make it occur by sheer force of will, and it feels real enough… but it’s an invention of my own mind. It’s perception, not reality: subjective, not objective; a conjuring trick I do in my head – a bit of mental Ali Bongo.

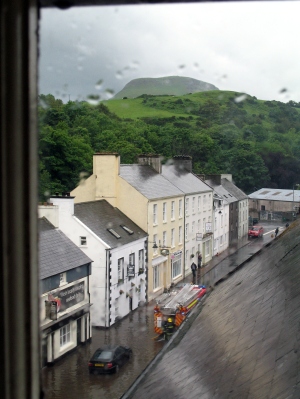

So I sit here in the living room on the second floor of a 195-year-old stone tower in the town of Cushendall, Northern Ireland – a building built to “imprison idlers and rioters” or so it says in this leaflet I have on my lap – and I sense the presence of… nothing at all.

Like the hopeful moments here when I click the Facebook icon on my phone, and stick my arm up to the window hoping to catch the scent of a signal, I’m desperately trying to experience the lick of the past in this place. But just as there’s inevitable disappointment when the ‘Connection Lost’ message appears, there’s nothing doing. Don’t get me wrong; I can see the past all around me, and if you’re in Cushendall then you can’t ignore this place – it’s on the town’s central junction after all, like a kid’s toy fort grown Gulliver sized – but I can’t feel its touch. There are no idlers or rioters here… unless they’re like an ectoplasmic Woody and Buzz, clamming up just as I open the door.

And I can’t even force it to happen in spite of the building’s age and function: this is a tower that holds the promise of spectres, but delivers none.

So I’ve got nothing to tell you.

My story can never begin.

—

Yesterday, I went out for a drive with Zippy, who manages this building, and who keeps popping by to check I’m OK. It was a Tuesday afternoon – early closing in the town, and therefore also in the butcher’s where he works – and he said he had a couple of hours to kill, and would I like to go out and about with him to see a few sights that are too far to reach on foot. He was standing there in his butcher’s apron, almost dancing on the spot with this restless energy he has, twitching and gesticulating with his fingers, rattling his keys, eager to get on and get out and get going.

At first I’d said I was on a roll with my writing, which was an exaggeration as I hadn’t written much; but then I knew it would be perverse to say no when I’ve come all this way, and I said I’d love to go for a spin, and he said he’d be back to collect me “once I’ve got the smell of meat off me,” and three quarters of an hour later we were on our way.

We visited Torr Head, with its derelict coastguard station, climbing up a rusted and crumbling ladder to take in the view from the roof. Except there wasn’t any view, or at least, no more than a wall of white cloud, as the weather was misty and damp.

“On a good day you can see Scotland,” said Zippy, and I told him that even though we couldn’t see it, it was still a good day, as I like the way that fog wipes out all backdrops and brings the view closer, and makes for a melancholic mood. I didn’t really need to see Scotland, but I did love this smoke machine world.

And as I willed myself to hear the churn of past voices, figuring that the fog would somehow make it easier to do, I noticed that Zippy was skirting the perimeter of the roof looking… inwards.

“We used to come up here,” he said, “smoking and drinking.” And in his eyes I could see that the past was here with him, gazing him in the face. And yet my past – my vibrations of Sheffield and Liverpool – they were far from here, and no amount of swirling mist and shrunken horizons were going to bring them to life.

We drove to other places too – to ruined Layd Church, and to the crumblings of Red Bay castle – and everywhere we went, Zippy would mention that him and his friends would once have partied there, necking cider among the ancient stones and sharing blowbacks and getting up to the kinds of things that teenagers do.

“In a little town like this you can’t drink in the pubs under-age,” he said, “because everybody knows you. So you have to use your imagination.”

And even on top of that coastguard station, that imaginative thinking was now haunting him; because whatever any of us do in life, things will never again have the novelty and charge that they did when we were young, and the energies he laid down all those years ago were once again crackling through his veins.

And I thought to myself – he is seeing ghosts, whatever I believe.

—

I’m three nights in to this visit; after this, there will be just two more left to go. I’m already growing used to my location: each time I pop out to the shop, I am less surprised than before about the place I’m heading back to.

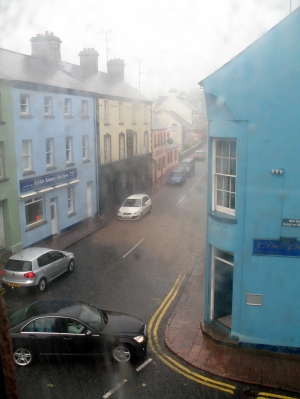

This evening though, Cushendall was transformed. I was listening to the heavy rain battering at the kitchen skylight when a dark figure flashed by the window and Zippy’s face appeared in the back door glass, water pouring from the brim of his hood. He rattled at the glass with his keys and muttered, “No rush, no rush,” as I ambled over and struggled with the lock.

Once I got the door open, he marched straight in, trailing water across the floor like a towel that’s been dunked in the bath.

“You OK in here?” he asked. “Is there any water coming in?”

I assumed he meant through the roof, and I admitted that I hadn’t been up to see.

“I think you’d better look out of your window,” he said. “The town’s flooded.”

From up in the living room I could see the fast ripple of surface water gushing down the hill behind the tower. From the opposite window, I saw a slowly advancing shoreline of silty brown liquid, as if gallons of coffee had been upturned. But it was only once I reached the top bedroom and looked out towards the library that I saw huddles of citizens calf-deep in water, and waves splashing up against the chemist shop.

I suddenly felt foolish, every inch the isolated artist secure in his ivory tower. So I grabbed my jacket and ran out into the street, and made a bee line for Zippy who was marshalling traffic, preventing cars turning into the flooded road while fifty yards from where we stood, a fire engine pulled in and began pumping.

I was a spare part, of course; not required in this hour of the town’s need. Here were people whose homes and businesses were under immediate threat of submersion, while my precious gear – my laptops and cameras and notebooks – were safe and secure three floors up above the street.

Unable to think what to say or do, I attempted a joke with Zippy: self-deprecating, designed to advertise my sense of inadequacy.

“I must have looked a typical creative type, totally oblivious in there while mayhem reigned around me?” And I punctuated the comment with a light snigger, to indicate I was fully aware of how pathetic I must have seemed.

To his credit, he did chuckle. But said,

“You should have been here in 1991 mate. That was a real flood.”

And I realised that this wasn’t mayhem or the coming of civilisation’s end. This was a hazard inherent in the layout of these streets; potentially recurring every time there’s a downpour that intense. And while I saw a town that had flipped in a couple of hours from a sun-trapping seaside village into something like New York in that film The Day After, Zippy and his friends and neighbours were overlaying the scene with floodings and fears from the past; transforming the image of that street into a double, or triple, or quadruple exposure, wisped across with trails of dead moments, like a Daguerreotype of a bustling city square.

But my memories of Cushendall are new born; which means that if I ever come back, I might finally be able to suspend my disbelief and tap into these moments once again; and if you want to call the simple fact of memory a conjuring up of spirits, then so be it.

I don’t believe the souls of occupants past can be found here, but should I return, I’m sure it will be easy to pretend I’m scooping up the self I left behind – when the flood came, when the fog came, when the nights without my family began to tell.

Because here and now, I swear: there really aren’t any ghosts in the Curfew Tower. But just because I don’t believe in them, it doesn’t mean they’re not here.

Waiting for me. Next time.

I wish…

Text, audio and images © Damon Fairclough 2012

I produced this article and its accompanying audio cassette at the Curfew Tower in Cushendall, County Antrim, in June 2012. You can find out more about the tower and how I came to be there by reading my article The House of King Boy D. I’ve also published my Curfew Tower journal – a diary of my five days in Cushendall.

Share this article

Follow me