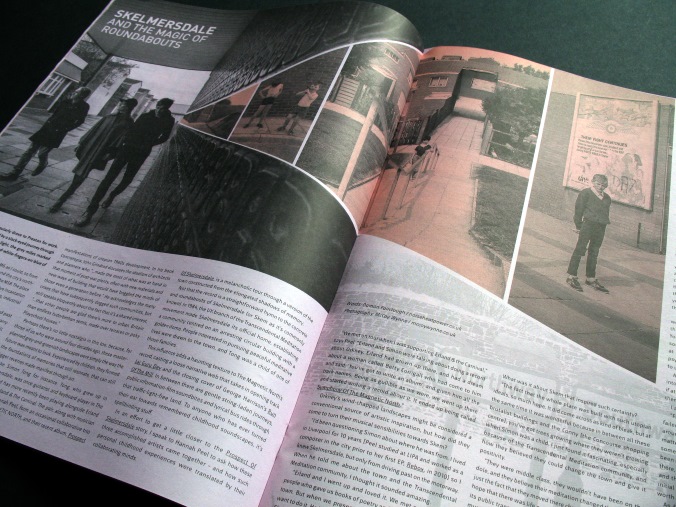

Skelmersdale and the magic of roundabouts: talking to Hannah Peel of The Magnetic North

Over the years I’ve written plenty about the hold that music, memory and place can have on the imagination. My thoughts have tended towards the locations in which I’ve lived – the pop capitals of Sheffield and Liverpool – but when Bido Lito magazine suggested I listen to Prospect of Skelmersdale by The Magnetic North, and maybe interview the band’s Hannah Peel too, I discovered that even hidden West Lancashire new towns can conjure spectral melodies of their own.

Not so long ago, I regularly drove to Preston for work. Each day was bracketed by a slack-eyed journey through morning mists or fading light, the grey miles marked by motorway punctuation – the forked-white-fingers-on-blue of regulation Highways Agency signage.

I soon learned to avoid as much of the M6 as I could, so from my south Liverpool home I would swoop round the city’s north-eastern rim via the M57, then take a right along the M58. The place names became my commuting mantra, a meditative incantation through post-war estates and edgeland settlements, industrial parks and expressway towns.

One place in particular always caught my eye. As I sped past its southern edge, the name ‘Skelmersdale’ seemed to carry an ancient echo, perhaps Norse or Celtic in origin, a linguistic provenance that seemed at odds with the tangle of slip-roads and central reservations that formed its surrounding landscape. I wondered if I should take the exit and see for myself how a 1960s new town – designed to accommodate Liverpool families decanted from slum-riddled inner city districts – had been laid over a settlement that dated back to the Domesday Book.

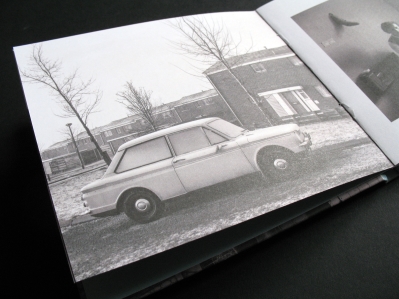

Skelmersdale was designated a new town in 1961, and its plan of roundabouts and subways was laid down over the subsequent decade. I’m not alone in being intrigued by such manifestations of utopian 1960s development. In his book Concretopia, John Grindrod discusses the idealism of architects and planners who “…made the most of what was at hand in that moment of post-war plenty, often with new materials and new ways of building that would have boggled the minds of those even a generation before.” He acknowledges the many crises that have subsequently dogged such communities, but still speaks eloquently about the fact that it’s a shared interest, “…that other people are glad there’s more to urban Britain than endless tudorbethan semis, made-over terraces or poky Playschool houses.”

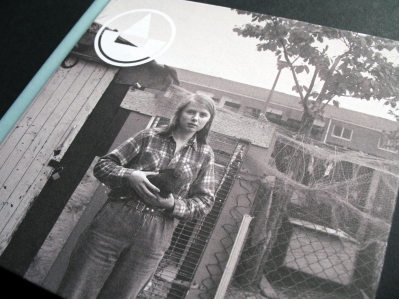

Perhaps there’s no little nostalgia in this too, because for those of us who were around four decades ago, these masterplanned grey-and-greenish landscapes were simply the way the future was meant to look. Experienced by children, they formed the foundations of memories that still resonate, that can still trigger reveries made manifest through art.

Take Simon Tong for instance. Tong, who grew up in Skelmersdale, was once guitarist and keyboard player in The Verve, and has more recently been playing alongside Erland Cooper in Erland & The Carnival. The pair, along with musician and singer Hannah Peel, form an occasional collaborative trio called The Magnetic North, and their recent album, Prospect of Skelmersdale, is a melancholic tour through a version of the town constructed from the elongated shadows of memory.

Not that the record is solely a hymn to the concrete and roundabouts of Skelmersdale (or Skem as it’s commonly known). In 1984, the UK branch of the Transcendental Meditation movement made Skelmersdale its official home, establishing a community centred on an arresting circular building with a golden dome. People interested in pursuing peaceful meditative lives were drawn to the town, and Tong was a child of one of those families.

This influence adds a haunting texture to The Magnetic North’s record, casting a loose narrative web that takes in opening track Jai Guru Dev and the closing cover of George Harrison’s Run of the Mill. In between there are gentle string-laden journeys, public information film soundbites and lyrical bus rides through that traffic-light-free land. To anyone who has ever turned their ear towards remembered childhood soundscapes, it’s spellbinding stuff.

In an effort to get a little closer to the Prospect of Skelmersdale story, I speak to Hannah Peel to ask how these three accomplished artists came together – and how such personal childhood experiences were translated by their collaborating minds.

“We met on tour when I was supporting Erland & the Carnival,” says Peel. “Erland and Simon were talking about doing a record about Orkney. Erland had grown up there, and had a dream about a woman called Betty Corrigall who had come to him and said, ‘You’ve got to write an album’, and given him all the track names. Being as gullible as we were, we went up there and started writing a record about it. It ended up being called Symphony of the Magnetic North.”

Orkney’s wind-chapped landscapes might be considered a conventional source of artistic inspiration, but how did they come to turn their musical sensibilities towards Skem?

“I’d been questioning Simon about where he was from. I lived in Liverpool for ten years (Peel studied at LIPA and worked as a composer in the city prior to her first EP, Rebox, in 2010) so I knew Skelmersdale, but only from driving past on the motorway. When he told me about the town and the Transcendental Meditation community, I thought it sounded amazing.

“Erland and I went up and loved it. We met some brilliant people who gave us books of poetry and things inspired by the town. But when we presented our ideas to Simon, he didn’t want to do it. He just said no one’s going to want a record about Skelmersdale. So it took us a while to convince him that it should be our next album.”

What was it about Skem that inspired such certainty?

“The fact that the whole place was built with such utopian ideals, so much hope. It did come across as kind of bleak, but at the same time it was wonderful because in between all these brutalist buildings and the Conny (the Concourse shopping centre), you’ve got trees growing where they weren’t growing when Simon was a child. I just found it fascinating, especially because of the Transcendental Meditation community, and how they believed they could change the town and give it positivity.

“They were middle class, they wouldn’t have been on the dole, and they believe their meditation changed things. I think just the fact that they moved there changed it, and gave people hope that there was life outside. I mean, Skem isn’t known for its public transport. It doesn’t even have a train station. So it must have been quite bizarre that all these people wanted to move there.”

These twin strands of idealism – the optimistic 1960s dream and the focused deep thought of the TM community – weave in and out of Prospect of Skelmersdale, but there is also a frayed melodic thread that hints at the sadness at the edge of such urban/rural locations. The track Sandy Lane opens with an aching flute line that I find naggingly familiar, and it’s only after repeated plays that I realise it’s a direct quote from John Cameron’s beautiful score for the film Kes.

“Skelmersdale is pastoral,” explains Peel, “and underneath the town it’s very beautiful – it was all farmland. So I saw it through a kind of 1970s photographic lens in terms of using flutes, woodwind and strings. In the back of my head it was always a bit like a lost Kes soundtrack.”

However, while the Kes landscape is one of Victorian red brick clutching at smoke-throttled green hillsides, Skelmersdale’s once-gleaming concrete betrays its more recent gestation during the post-war building boom.

“It’s fascinating that you would build these new places and dump everybody there, and expect them to work,” says Peel. “Most don’t have town centres or communal areas, just shopping centres. So many of them didn’t work, especially during the 1980s, but I think Skelmersdale is one of the ones that has come through because of its surreal side.”

I wonder if Peel felt any tension between being an outside observer of the town, and the fact that Skelmersdale is not just an inspiring curiosity, but also home to almost 40,000 people.

“I was definitely aware of that,” says Peel, “more so than with Orkney. Skelmersdale is a tight community. The way we’ve approached our records is to have one person – Simon in this case – who draws on their experience and knowledge, while the other two bring their own perspectives to the place. But the reaction has been amazing in terms of people saying thank you for thinking of the town. It’s a positive record, and I’m really thankful that people like it.”

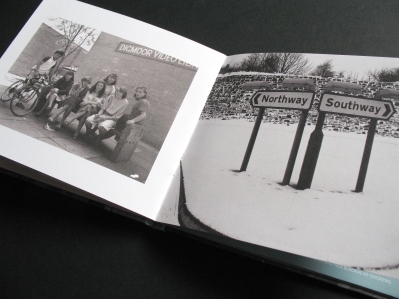

If there’s one thing the 1960s development corporations were good at, it was making promotional 16mm films about their visions of the future, many of them now available on YouTube. The Magnetic North make good use of this evocative source material, deploying paternalistic voice-over samples at strategic points throughout the album. It’s the British psychogeographic equivalent of the way Public Enemy used to use James Brown.

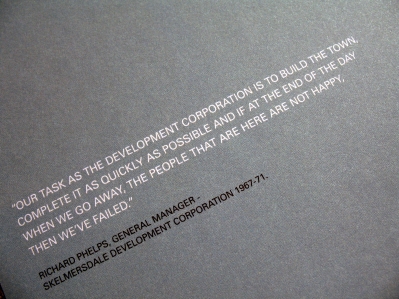

At the end of the track Northway/Southway, just such a voice intones, “Our task is to build the town… and then go away, and if at the end of the day the people that are here are not happy, then we’ve failed.”

I ask Peel for her Skelmersdale verdict.

“Fifty years on from when it was built, I would say it hasn’t failed. People are happy there and are very protective of it. But around the late 1970s, 1980s, it would have been a different matter. I think with any community, if you’re going to build something, it’s going to take a long time to develop, and it’s been nice to actually see that process. Even since we first went there, some of the housing estates are completely regenerated and there’s lots more building work going on. But I think the initial planners did fail in giving the town something that was worth holding onto for a while.”

As for me, I never did take the Skelmersdale exit while commuting to and from Preston. I suppose I was always too worried about being late for work or I was simply far too keen to get home. But having listened to the exquisite new town dreaming of The Magnetic North, I do feel as though, somehow, I’ve seen its “golf course in the moonlight, the heroes in the half light”.

It’s a memory that will stay with me. And once you’ve heard this record, perhaps a corner of your soul will remain forever Skelmersdale too.

Share this article

Follow me