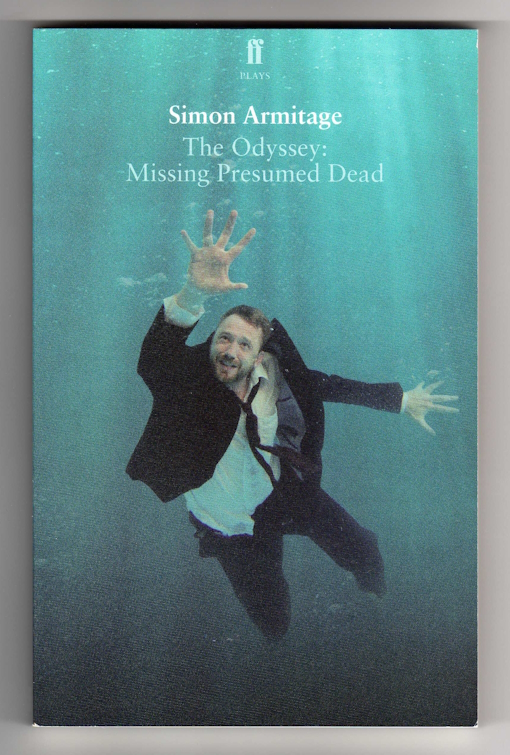

The Odyssey: Missing Presumed Dead reviewed at Liverpool Everyman Theatre

The Odyssey: Missing Presumed Dead is a play by Simon Armitage based on Homer’s Odyssey. This review is based on its run at Liverpool Everyman Theatre from 25 September until 13 October 2015.

We all became so blasé about the concept of a ‘journey’ didn’t we? Sit down, lift off, couple of gins, a nice snooze and then whooosh, applaud the pilot and back on the ground. Dublin, Paris, Bangkok, Sydney – the destination didn’t matter. The trials and tribulations of getting there were mere pin-pricks on the surface of life: a squawking baby, not enough leg-room, a portion of questionable food. Nothing that was ever going to kill you.

And then Syria happened. That woke us up. Human lives being tossed this way and that on the ocean. No ticket checks, no duty-free booze. Suddenly we realised that a delayed flight and a lost suitcase wasn’t ‘a nightmare’. Here were people on a journey, and they were – they are – experiencing a true living hell.

It seems extraordinary then that the new Liverpool Everyman production, The Odyssey: Missing Presumed Dead, should open while we are still in the middle of this tidal surge of desperate humanity. Just as in Homer’s original Odyssey, on which this is based, the story concerns a journey across continents, by sea and on foot, in which obstacles of all kinds are arrayed in opposition. Written by Simon Armitage and directed by the Everyman’s associate director Nick Bagnall – the same team that created the Royal Exchange’s The Last Days of Troy in 2014 – this world premiere makes explicit reference to today’s non-mythic movement of people. It’s just one of several ways in which the ancient world of monsters and torment bleeds into our modern world of politics and spin.

The play opens with a prologue read by Athena, daughter of Zeus, who then transforms swiftly into Anthea, daughter of our present-day Prime Minister – not Cameron, but another middle-aged white male played with a simmering sense of entitlement by Simon Dutton. Anthea is a senior aide to her father, a man with a minor problem that needs solving: as a pre-election stunt, a cabinet representative must be seen to attend a crucial World Cup qualifying game in Turkey. But he or she must be found quickly, as the make-or-break football match is imminent.

The Prime Minister settles on an ambitious, on-message politician called Smith, largely because he’s northern and likes beer. With a few tossed-away words, the PM scuppers Smith’s plan to get home to his family in Cumbria where his son is turning 18. Smith protests weakly, but the divine mind is made up; the modern-day Zeus has moved his man into position. Istanbul beckons.

It’s an intriguing set-up played with great comic timing, though it quickly turns dark as Smith becomes embroiled in a Turkish bar-room brawl. There are pissed-up England fans and chanting, and suddenly he’s in the middle of a fight. Someone is hurt, and it’s possible that Smith is to blame. With his translator and two brutish chest-beating fans in tow, Smith disappears into the Istanbul night. Pursued by police, threatened by locals, the quartet have no choice but to leap into the sea.

This is no jump and splash into a glittering, beach-resort Aegean. This is a life or death plunge from a moonlit dockside, and when the four hit the water, they not only break the surface of the sea, they also pierce the skin that separates reality from a world of ancient myth.

From this point on, the play laps back and forth between the present day and the classical past. Smith and his compatriots are now Odysseus and his men; together, they face the marvels and horrors of those legendary tales as they struggle towards their goal. “Home,” says Odysseus/Smith repeatedly, “will I ever reach home?”

The Odyssey: Missing Presumed Dead is presented simply and often staged beautifully. Signe Beckmann’s stepped arena design enables past and present to co-exist without confusion, and with its curved, burnished backdrop and deep semi-circular apron, it allows for evocative atmospheres to be conjured from the purest theatrical effects: some wonderful lighting, some fine melodies, some strong acting. Many of the set-piece mythic confrontations are particularly exquisite, with the song of the Sirens creating real spine-tingles, and a pantomime ogre of a Cyclops who “farts in gods’ faces and pisses on gods’ feet”. In this context, the hissing hydraulics of Odysseus’ boat seem rather over-engineered considering the subtlety of the effect.

The shifting tone of the piece is well handled, with deep poetics switching to one-liners and laughter, and three distinct plot strands being spun simultaneously. There’s the beleaguered journey itself of course, but we also follow the Prime Minister’s present-day efforts to minimise the political scandal, along with the struggle of Smith’s wife Penelope and cusp-of-adulthood son Magnus to deal with their hounding by the press.

Up until the interval these three strands weave together well, but during the second half, the momentum begins to drop. While Armitage’s poetic language remains delightful to the ear, there isn’t much he can do to prevent Odysseus’ journey becoming just one thing after another – that is to say, it is episodic by nature and there is little sense of “what’s going to happen next?”. I’m no classical scholar – Jason and the Argonauts every Christmas is about as deep as I’ve ever delved – but even I pretty much knew what was coming. And while that’s true of any great story retold, this is not a plot that feels tightly wound and compelling. By its mid-point, its tension becomes dangerously slack.

Even Armitage himself seems to recognise that this languid motion might not have the sustained energy of a more conventional plot. “We’re not drifting aimlessly as some of you think,” Odysseus tells his men at one point, though perhaps this is the author addressing the crowd. “We have a direction and a destination, and we’re on course.”

While spending so much time with Smith as Odysseus is not a bad way to spend the evening – Colin Tierney’s perplexed-yet-intelligent performance remains one of the night’s real pleasures – the downside is that Smith as Smith, the cabinet minister and often-absent husband and father, seems under-developed. His second-half meanderings through antiquity send him this way and that, but those left back at home, firmly in the present, can do little more than wring their hands and pronounce him to be still lost, still missing. We learn about him as a person in the telling rather than the doing, and that can never satisfy quite as much as seeing his character revealed before our eyes.

However, while the play’s overall flavours are weakened as the narrative comes off the boil, its ingredients remain satisfying and well worth tasting. From Britain’s relationship with Europe to the mercenary nature of the press, Armitage has plenty of opportunity to pass comment with cutting soundbites and wit. Enriched by his poet’s turn of phrase, the piece is lyrical but never short of laughs. A particularly blunt-edged scene just before the end delivers a proper wallop to the funny-bone even as a chill wind threatens to blow us all home.

And then there are those real-world parallels of course, the metaphors and allusions that don’t just hint at our contemporary experience of the world, but seem to foretell it, to warn us of our human plight. If the original Odyssey is an archetypal journey from a place of anguish, through difficulties, to a place of rest, it’s an endurance test from which our everyday experience of travel has divorced us. But then we look at the television, at our iPads, at our screens – at the faces of people suffering every indignity just to move from one place to another place somewhere else – and we realise that for almost all of human history, a journey wasn’t expected to be painless.

It was – and still can be – a place from which you might never come back.

The Odyssey: Missing Presumed Dead ran at Liverpool Everyman Theatre from 25 September to 13 October 2015.

This review originally appeared on the website Northern Soul.

© Damon Fairclough 2015

Share this article

Follow me