The paste land: a memoir from Sheffield’s flyposter frontline

The illegal collaging of flyposters was a growth industry in the Sheffield of 1985. So I rolled up my sleeves, I got stuck in, and like so many others, I wore my heart on the wall.

The subways, the bridges, the car parks, the precincts: this was a city constructed of paper and glue. Across every blank facade and each vacant parade there were thick crusts of papier-mâché, propaganda gone hard. Screenprinted, Xeroxed, stencilled, felt-tipped – these posters could be hand-made in attics or churned out by machine, but however they came into being, the layers of events and opinions seemed to keep our city standing even as we imagined the foundations were breaking apart. They held together walls that would otherwise collapse and masked the windows that glazed the abyss.

As the layers thickened, they were picked at and prised away from the wounds that they covered: they were flyposter scabs, but no healing occurred underneath. These were bomb sites, closed shops, parks made of breezeblock – all bound together by newsprint and paste. But even in the midst of this bandaged decay, the posters continued to spread their word, evidence that we retained a desire to meet, to play, to argue and fight. Here were meetings and demos, concerts and gigs; and we yearned for an audience, or for friends to join in. This agitation and hedonism – we couldn’t do it alone.

In Sheffield in 1985, the industrial canvas was blank. There was a lot of space to be filled; there were a great deal of things to be said. For just a few quid, a room in a pub could be yours – a void into which you could stuff musicians, revolutionaries, big thoughts, fat chances. Bands could play krautrock and hurl fruit at the crowd. Lads in round specs could prepare for insurrection. Nascent stadium rockers could charge 20p on the door. And across laminated tables ringed with ale, the stories of all of our futures could be written – so long as we were out by half past ten. And every event needed its poster, its place on the wall; a call to arms, or a simple decree: meet in the Brown Cow, the Mail Coach, the Howard, the Red Deer. Anything could happen – though it probably won’t.

In 1985 I was out there myself, sticking revolutionary bills where they weren’t wanted and thickening Sheffield’s papery skin. In the city landscapes of my mind, our collective efforts created an atmosphere fit for Ten Days That Shook The World, complete with a tsunami of propaganda that would sweep fellow citizens off their feet. In the actual landscapes all around me, I fear the effect was more akin to litter blown against a fence or plastic bags tangled up in a tree. Still, I was blind to that. To me, the posters meant urgency and panic, and the necessity of taking a side. And by chance I caught a few of these posters on camera, preserving my handiwork for future contemplation.

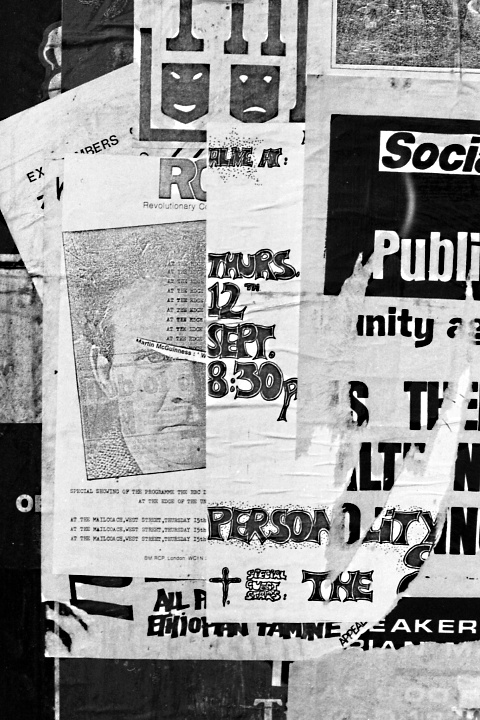

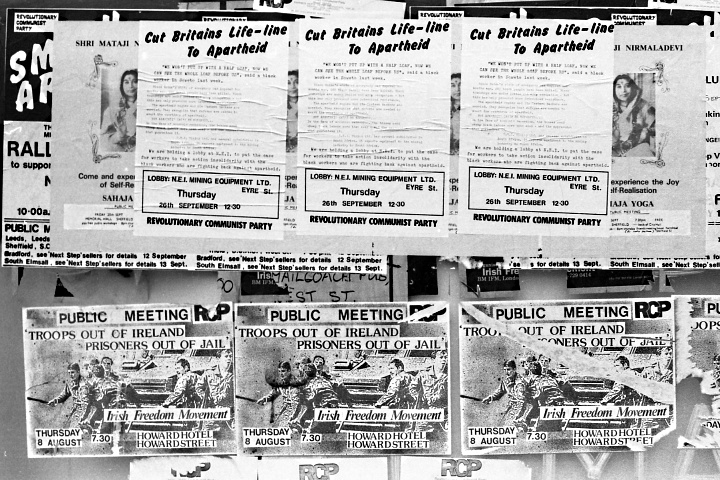

In one shot, there’s the truncated face of Martin McGuinness, neatly bisected by an ad for a gig. And in the other, there’s a brazen row of posters for a public meeting about Ireland – the wallpapering of which was perhaps the most audacious act of my short career on the paste. They remained there for months afterwards, thrilling me to the bone each time I walked past on my way to Boots. “He did it!” they seemed to call out. “He put us here. There’s your pesky stick-up kid!”

But I hurried past. Anonymous. Unknown.

—

We mixed the paste in a carrier bag and took it into town on the bus. The posters were rolled and stuffed inside a canvas satchel; we were dressed to get wet, to get sticky; we carried no ID, no diaries, no address books – nothing that would reveal who we were.

But now the faces come back to me, though names have been changed: there was ‘Angus’, and ‘Jenny’, and me. Angus had once been an anarchist, was now a communist. He knew all about flyposting; was a veteran of bands and anarchism and the politics of sticking your message to a wall. He knew which route to take and where to avoid; he knew the plainest expanses, the choice vistas of brick – though so many shops were empty and buildings undeveloped that in fact we were spoilt for choice. It was easy to find sites on which idle gazes would constantly fall – on Leopold Street, or Pond Street, or on West Street where people signed on.

I knew it was criminal damage, and instinctively, I wanted to do it after dark, but Angus said no, the best time to do it was around half past five or six in the late afternoon. People would see you but they would rarely intervene, and besides, all they wanted to do was to get home from work. If you looked confident and self-assured, they wouldn’t try and stop you. And anyway, look around you he said: these things are part of the landscape, they’re the city’s urban wallpaper. People expect to see them, they’re used to it. They probably don’t even know it’s illegal.

The police of course – we had to look out for them. That was Jenny’s job. She was an ex of Angus’s and also ex of the anarchist set. Sometimes we would see their old mates flogging Class War in the middle of Fargate. Except, they didn’t really sell their papers; they stood stock still in their black army surplus kit, holding up their mags and simply staring at the rat race, the grey suited fools who were complicit in their own oppression. Occasionally they would also have a flag – a big banner on sticks that two of them would prop against the floor and hold upright, catching the wind like a red and black sail. As it bulged in the breeze it gave them something to fight against, lent purpose to their struggle. But they never spoke to Angus or Jenny to acknowledge past friendships, and they in turn didn’t speak back. Comrades no more. Their mutually averted gazes were their personal homages to Catalonia; an eternal revolutionary suspicion – Marx versus Bakunin in front of Marks & Spencer.

The daftest time to do this, according to Angus, was late at night or in the early hours of the morning. Darkness wasn’t a cloak that would conceal you; it merely blacked out the world around you and made it obvious you were up to no good. Without the crowds of commuters around you, you would be seen by every passing police car and citizen. And being late-night citizens they would be short of inhibition, full of keg bitter; they would ask what you were doing and would potentially cause a scene. And because our politics were extreme, our material was inflammable. Those lads in their shirt sleeves and slip-ons, their Harmony bouffants and trim footballer ‘taches, they wouldn’t want to discuss the complex history of Britain’s role in Ireland. If they took one look at our posters we’d be in for a kicking. A real pasting.

Pun intended, Angus said.

So we pushed our way through crowds as they made their way home, Angus and I sticking together while Jenny stayed on the other side of the street. I had adrenaline jitters and a stomach that floated up into my chest. I felt at once both cavalier and desperately afraid; too young perhaps to appreciate the consequences should I be caught, but still aware that it wouldn’t be A Good Thing – though the profusion of posters all around us served to comfort me a bit. There was so much crusty paper on the city’s walls, I reckoned there must have been people out doing this day and night. If so many people were at it, could it really be so bad?

It was a heartwarming sensation to think of them, carrier bags of paste in hand, sodden bristles flapping at the wall. When you’re afraid of flying, it calms the heart to imagine your cabin crew shooting backwards and forwards through the air, day after day, without a second thought. And this edgy sense of ease was just the same. Bands did it, the Leadmill did it, the student unions and the rest of the left wing sects did it. So many bill stickers were on the prowl that it was a wonder we didn’t meet each other mid-glue, pasting over posters that were just a few minutes old.

Not that we would have done such a thing. There was a rule, though of course, it remained unwritten (until now):

Don’t obscure a poster for an event that’s yet to come.

And so we picked our first spot. The existing posters were now obsolete, the surface porosity was acceptable, its visibility was moderate to good. A nod to Jenny over the road and we were away, me unrolling posters and trying to keep them flat while Angus clutched the bag of glutinous liquid and slapped it onto the wall. He was fast, too fast; and seemed nervous all of a sudden. I couldn’t keep up with him and he snapped at me; demanded that I get the posters out more quickly, keep them straight, stop them getting caught on the breeze. I had imagined we’d stick up one poster and then move on, but Angus said that wasn’t enough. Again he said, look around. One poster will vanish among this lot. We need three together at least; the repetition will have an effect. It gets to people, reaches them deep down, below the level of consciousness. When they see our posters, again and again, row after row, the fraction of a fraction who are primed to respond will do so. This is not a service we’re providing; it’s not publicity. It’s hypnotic warfare on the streets of Sheffield.

We placed three together, and moved on. A couple here, a trio there. Here, too busy – move on. Stop, fluster, paste, walk. There were anxious moments when Jenny disappeared in the crowd. Had she seen the police and legged it? Suddenly it was impossible to know.

But no, she was there, she was fine. She let a smile snap across her face and then it was gone; it was as if she didn’t know us, which was exactly how it should be.

And across the city we skittered: up Howard Street, around the Poly, through Arundel Gate subways, the Hole In The Road, and High Street by the bus stops. This was where the crowds really thickened, where there was no escaping the puzzled stares of commuters on their way home. But it was too good to miss: just below the junction with Chapel Walk there was an angle of glass that faced everyone walking up into town. The shop that it fronted was abandoned; it was now covered in paper – announcements, manifestos, acronyms by the dozen. It was here that we got five in a row, pasting furiously alongside tired shoppers, weary workers, people without the energy to lift a finger. And that was the thing: it wasn’t worth their while to bother. Where prosperity was receding, the posters would always flourish; and the city was already dressed head to toe in this papery gown. Five more posters, even right here in the retail heart of town, made no difference at all. The damage had been done long ago; so best save your breath.

Five in a row – and they were nice big A2 ones as well. If we’d have known of such a thing, we’d have high fived in honour of our five: we were ecstatic, delirious. Then we continued up Fargate, walking quickly, on air. There was nowhere to post on that stretch – those shops were still kind of thriving. But then we turned right at the top by the fountain and along past the Peace Shop. It was a narrow lane, a cut through from Church Street, that bordered a site that was about to be developed. We didn’t know it, but the demolition and construction that would take place along there would signal the end of recession – for a few years at least. We were placing our posters on walls that would soon be rebuilt, that would become Orchard Square – a twee post-modernist haven of shops.

At the end we turned left, into West Street; the desolate zone at the back of the City Hall. There was the NUM headquarters, permanently half built, a construction that already seemed out of step with the times. Only one year before, this had been the miners’ strike’s ground zero with its arguing crowds, newspapers of all shades, banks of policemen and Special Branch listening in. Now though it was quiet, even at rush hour. Our last few posters went along the side of SCCAU – the Sheffield Co-ordinating Centre Against Unemployment. It was a squat brick low-rise – at the time of writing, still there; though increasingly incongruous amid West Street’s modern Euro styling.

And done. A pint then, in The Saddle. Nerves a-whisker, tales told nineteen to the dozen; we were already aggrandising the operation, turning uncertain moments into almighty clashes with The Law; and fluffing things out a bit, just as I’m doing right now.

I sank back on my seat and enjoyed the sense of coming to rest. I was at ease, and still in that legal-drinking hinterland after my eighteenth birthday when it was novel to drink ale in a pub and not have to watch my back.

“Are you old enough love?” they would ask.

“I am,” I’d reply. “Yes I am.”

And with paste under my nails and the box-fresh cloak of an outlaw, yes indeed; old enough I certainly was.

—

A few weeks later I went back with a camera and froze those posters in time. They were being progressively obliterated, vanishing beneath other moments that happen in rooms above pubs: public meetings and mates with guitars. So I caught them in a split second, to be excavated in 2009.

There were flyposters before then and since, of course; but not these ones; not the ones I added to Sheffield’s tatty old canvas – a landscape that had been scraped raw for ten years. They were lucky to survive as long as they did because, a few days after our adventure, it was noticed that the SWP had followed our route and covered up a good deal of our efforts. This was a breach of etiquette, deliberate flouting of the unwritten rule. It was the kind of act that could have tempted us to tit for their tat; but in the event, one of our comrades just chased a bespectacled socialist worker as he rode his bike down Fargate and more or less threatened to bust his legs. Subsequent posterings remained unmolested I seem to recall.

So here they are, my few posters. Urgently plastered into place, they always lived on borrowed time; but now that sense of frenzy is suspended, the message has yet to escape. And this, stuck here, is the moment before they were gone.

Text © Damon Fairclough 2009

Images © Damon Fairclough 1985

Share this article

Follow me