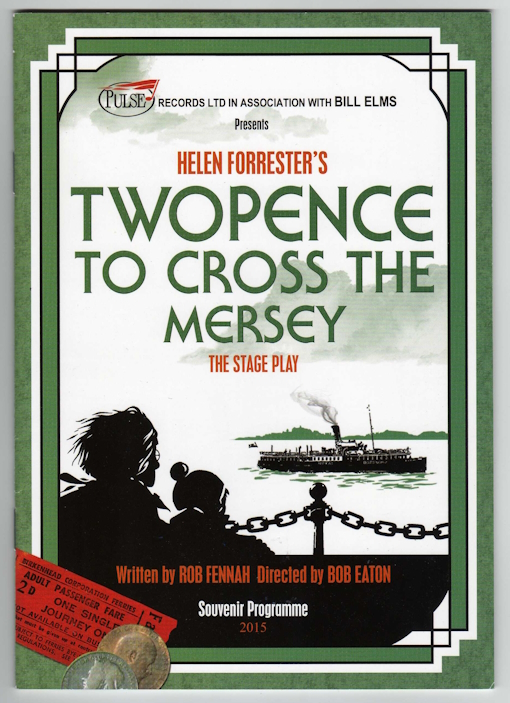

Twopence to Cross the Mersey reviewed at Liverpool Epstein Theatre

Twopence to Cross the Mersey is a play by Rob Fennah adapted from a memoir by Helen Forrester. This review is based on its run at Liverpool Epstein Theatre from 10-28 March 2015.

I like to think I know a thing or two about hardship. Just the other night, for example, there was nothing on telly so I subjected myself to Justin Bieber: Never Say Never on Netflix. And altruism too, I’m good at that. When I arrived at the Epstein Theatre last night for this new production of Twopence to Cross the Mersey, I gave up my aisle seat to a woman who needed it more. Then I scrunched into place further down the row and felt good that I’d helped someone out.

But of course, even I know almost nothing about these things compared to the family at the centre of this story. Twopence to Cross the Mersey originally appeared as a volume of memoirs by Helen Forrester in 1974; it tells the story of her family’s precipitous fall from middle-class comfort in a southern market town into seething poverty in 1930s Liverpool. Or rather, not so much the fall as the landing. Twopence to Cross the Mersey is what happens when, having been bankrupted by the Great Depression, they finally hit the ground, their sense of identity and entitlement lost on the journey to Lime Street.

The book proved something of a phenomenon, heralding Forrester’s prolific writing career and subsequently playing to packed houses as a musical. This new stage play, written by Rob Fennah and directed by Bob Eaton, carefully strips down the story into a series of interlocked scenes, using a great deal of fourth-wall-busting narrative to sweep us briskly through the tale.

The result is a sparse rendering, often more storytelling than drama, that relies on subtle shifts in lighting and sound, and a swift parade of vivid background characters, to add dynamism and colour. If the central family are brittle and chilly – their clipped well-to-do accents are hard to warm to, though their plight is a desperate one with apparently no hope of work or salvation – it is these more fleeting performers who speckle the production with vitality and wit. Their support is solid and often hilarious as they bob in and out of view, proffering help to the family or ripping them off, rarely without an added twist of acidic Liverpudlian prose. Particularly strong are Jake Abraham, Brian Dodd and the wonderful Eithne Brown, a Liverpool theatre favourite who shines here in as many as nine different roles.

This is where the production is most alive – when it speaks in regional rather than received pronunciation, and seems to pursue an almost Dickensian path. And it is here that we have to remind ourselves this is not Dickens; it is not the Victorian age. This is Liverpool of rather less than 100 years ago, when my own grandparents were in their late teens and twenties. The welfare state was still 15 years away, the workhouse was your safety net and the coffin was your final full stop.

We’ve come a long way in the meantime, but that doesn’t mean we might never go back.

It certainly seems as though the 1930s are closer than we think, and perhaps that’s one reason why the play reminded me on more than one occasion of Judith Kerr’s When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, the semi-autobiographical story of a Jewish family’s flight from Nazi Germany. I worry that I’m being glib, because Kerr’s book was about deliberate political persecution whereas Forrester’s memoir is ‘only’ about economic flight – an attempted escape from bankruptcy that terminates in terrible squalor. But both are told by little girls who must endure much, becoming selfless and strong at just the age when today’s kids are meant to do the opposite – in the popular imagination at least. But in these two tales, we witness the economic disasters of 1930s capitalism – and by extension, all economic disasters including today’s – rendered not as share prices in a newspaper, but as detonated lives in a Europe that was heading for the abyss.

Ultimately, Bob Eaton’s production tells a rich tale, of a teeming and stratified Liverpool in which a baby’s life could be saved by a random, very human, act of kindness, but a family could be despatched into penury and a child locked out of education by their own parents due to forces way beyond their control. Without being propagandist in any shape or form, its message is inescapably a fighting one: if we’re not careful, those forces may gather again.

Maria Lovelady, in the lead role, takes the weight of this play on her back and presents Helen Forrester as a stoic, though often self-doubting, character. Her shoulders sag and her hair grows lank as poverty bites, her childcare duties grow ever more onerous and her instinct for survival begins to ebb. There is an Eden in sight, just across the Mersey on the Wirral, where her grandmother lives and where she imagines salvation might reside. But it costs twopence to cross the river, and as she says while gazing across the city’s mythic artery, “it might just as well be a million pounds”.

Perhaps this is where my sense of hope must flourish. Because while our world may face economic danger, at least we still have our benefits system, we still have our schools. For all my Bieber-ish ambivalence, we even still have Netflix. And even though it now costs £2.30 to take the ferry’s breeze-blown ten-minute commuter service, at least I can still afford that.

Twopence to Cross the Mersey ran at Liverpool Epstein Theatre from 10-28 March 2015.

This review originally appeared on the website Northern Soul.

© Damon Fairclough 2015

Share this article

Follow me