Unearthing the unfinished city: an introduction to the book Brutal Sheffield

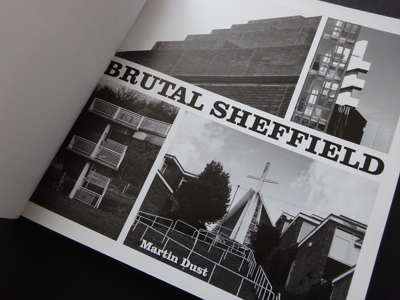

Brutal Sheffield, by Martin Dust, is a photographic record of architecture and brutality – a trek through the sullen-faced car parks and future-past churches that became the accidental backdrops to our lives. The text that follows is my foreword to the book – I was chuffed to be asked to consider Martin’s brooding photographs and contribute a few rain-stained city memories of my own.

Stashed away in a corner of my house, I’ve got a small pile of old school exercise books. ‘City of Sheffield Education Committee’ they say on the front in stern black print; each one also features my own hesitant scrawl spelling out my name.

I pull the fattest one from the pile and gaze at the cover.

‘Geography’, it says. ‘September 1978’.

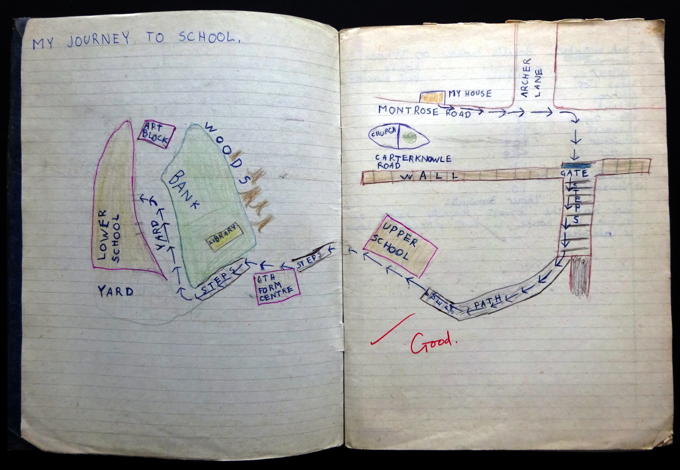

I open the book at the first double spread – the first project at the start of a new academic year, in a new school, where I wore scratchy new trousers and a blazer that held me rigid as a plank. Stretching across the two pages is a map – hand-drawn, not to scale. It’s a fragment of Sheffield, a tiny portion of the city. But in that September at the back end of the 70s, when I drew it with a nibbled pencil and inked over it in biro, it was roughly nine-tenths of the world I knew.

There’s my house and a stubby length of Carterknowle Road. There’s an odd scribble to indicate the weird little brick church we could see from our living room, and then there are the steps and cinder paths and grass banks and woods that lined my ten-minute walk to school. But there the map stops. No hinterland, no environs. Within these few ballpen lines are the doors I knocked on, the gardens I played in, the streets where we went out on bikes.

I flip through a few pages, and there are more maps – some drawn in pencil, like the first, and others in pale pinks, blues and greens. They’re the tell-tale pastel shades that reveal these maps had been churned through the school’s duplicating machine and handed round by the teacher before being Sellotaped into my book. Little by little, each map expands my world – from the school’s wider local area with its Thornton’s factory, its quarry, an edge of Millhouses Park, to a map showing the whole of central Sheffield marked with my favourite locations: Redgates toy shop, Western Jean Company, the Gaumont cinema and the Hole in the Road.

I keep turning the pages, keep seeing Sheffield grow as the maps and diagrams proliferate. This one shows rivers, the next one shows motorways, and this one is a slice through the city. ‘A Cross-Section of the Don Valley at Tinsley’ it says above drawings of steelworks and gasometers, cooling towers and terraced houses. Like a cutaway sketch in a medical text book, it exposes the layers of the city’s calloused skin.

The Sheffield in these exercise books is a city of industry, unmistakeably. It’s a place where an optimistic future is still being built – just about. It’s the city I spent the next few years discovering as I roamed ever further from the first map’s truncated childhood kingdom – and it’s the place where I learned that the future doesn’t always do what it’s told.

In 1978, Sheffield was still trying to be the city that post-war planners had hoped it would be: a smoke-free metropolis in which concrete schemes were stacked up and strung out across hillsides, and where a side-burned and mini-skirted population could flit from workplace to leisure palace while grooving to some uptempo jazz-pop. But as I scuttled through its subways, traversed its concrete walkways and took buses that charged fares that cost fuck all, I realised that its benign and beneficent masterplan had gaps in it, and the more you looked, the more you saw an awkward Sheffield that was still poking through.

They’d cleaned up its air, but they hadn’t wiped out all its workshops. They’d sliced dual carriageways through its back streets, but in between, they’d left carcasses built from brick. Over here there were arts towers, ziggurats and tower blocks, but over there you’d find factories full of ghosts.

I assumed that in time, Sheffield’s new world would be signed off and completed, and such spectral relics would be wiped off its map. Because I was too young to realise that my Sheffield wasn’t the last Sheffield – and that a city’s future, while often being promised, isn’t something that actually arrives.

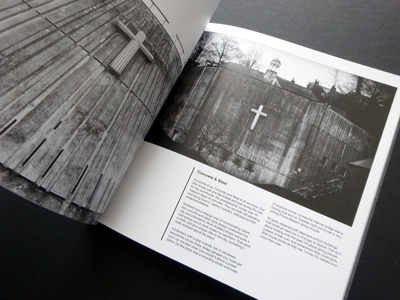

I get it now, of course. I see it in Martin Dust’s mesmerising photographs, in which I see Sheffield’s continuing architectural stratification – a process that involves designing tomorrow, and yet never finally drawing the last line. Along the way there have been attempts to wipe out utopias and detonate past certainties, and build new versions of new visions in their place. And yet throughout Martin’s photos of the city – images captured between 2018 and 2021 – it seems to me that yesterday is vengeful, and the awkward and stubborn still break through.

Now though, it’s those nobbled edifices and snarling façades of Sheffield’s post-war project that cling on like barnacles to a rock. When I was drawing my maps and discovering my city, these fortress-like housing schemes and arrowhead churches were the architectural shock troops of a future that was still to arrive. But now on page after page, in image after image, they’re like the survivors of a battle that’s been and gone.

Brutal Sheffield is both a portrait of this environment and an excavation of memory, a trek through the city that provides the context and inspiration for so much of Martin’s art. Because while I was walking these streets, peeking round corners, creating Sheffield myths and legends of my own, Martin was mapping his own brutal Sheffield and now these pages reveal something of that tale.

Whether he’s uncovering lost rehearsal rooms, remembering ex-record shops, or capturing the poetry of concrete and glass, his photographic world is one in which sullen-faced car parks can conceal fragmented recollections – and become the accidental backdrops to our lives.

I flick back through the pages of my old exercise book and I’m struck by how little of that Sheffield remains. The gasometers and cooling towers, Redgates and the Gaumont, even that great modernist vortex that everyone knew as the Hole in the Road – all erased. And back at the first map I looked at, the story’s the same. Almost every building, except my old house, has now gone.

It’s lucky, then, that maps and photographs will still tell their stories. And they’ll do it even if that’s all we have left.

Text © Damon Fairclough 2021

Images © Damon Fairclough 2021 and 2023 (all photographs in the Brutal Sheffield book are © Martin Dust)

This piece originally appeared in the book Brutal Sheffield by Martin Dust, published in 2021 by Revelations 23 Press.

It’s the first of three such pieces I’ve written for Martin Dust. The others are A very Yorkshire disaffection and The time that land forgot.

Share this article

Follow me