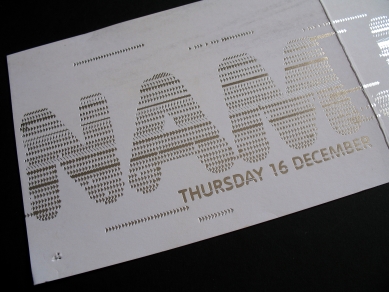

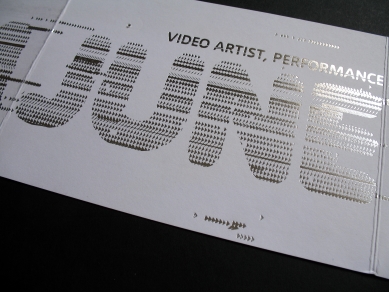

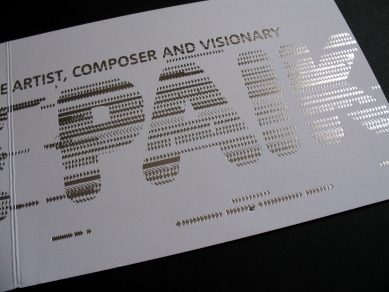

Vision on: the futures and pasts of Nam June Paik

When Korean artist Nam June Paik began working with video in the 1960s, he was taking up the tools of the future. His 2010 career survey at Tate Liverpool communicated the excitement of this prospect… yet also demonstrated how quickly those tools would become landfill.

The urge to peer into the future has been a human preoccupation for millennia; it’s something we’ve attempted via means as various as tea leaves, the I-Ching and the bulge of the crystal ball. But by the mid-20th century, the soothsaying glassware of choice had changed form; by now, it was the cathode ray tube that delivered The Future into our homes. As friends and families gathered round that tiny glowing window in 1953, in order to witness the Coronation of Elizabeth II, they were bound into a collective vision of what life on the planet would become: that the domestic interior could be the centre not just of relaxation and gentle entertainment, but also an arena that would allow vicarious participation in Great Global Events thanks to the humming valves of the television.

For the best part of five decades, that was our experience. The delicate glass trumpet that formed the business end of our televisions spirited into existence the shadows that kept us rapt: the moon landings, the Iranian embassy siege, Live Aid. We might have imagined the machines getting ever smaller and being worn as watches, or becoming giant-sized and taking over the house, but it was clear that the cathode ray tube’s gleaming eye would be watching over us as we watched over it for many years to come.

For most of us, the cathode ray tube was neutral technology; it simply delivered the images that others had chosen, like the paper that delivers the words in a book. To the Korean artist Nam June Paik though, its capacity to fascinate seemed to lie more in the manipulation of those rapidly firing electrons than in the stories that played across its surface. Thus, the survey of Paik’s career that currently takes over two major arts institutions in Liverpool – the Tate and FACT – features TVs dismembered and garrotted, with curious twisted light patterns playing across their screens.

In 1963, when Paik first began working with television – becoming, in the process, one of the world’s first video artists – such work represented engagement not with The Future, as understood by the masses, but with a concept way beyond what most people could imagine as the art of tomorrow. He allowed his audience to disturb the light that spilled across the screen – by manipulating huge magnets, or playing with the knobs of his seemingly jerry-built video control tower – and in so doing, allowed them to glimpse inside the box, to understand that all they were seeing were phosphorescent ghosts whose forms could be distended, or even destroyed, at will.

Under the powerful influence of John Cage, Paik worked initially as an avant-garde composer, flouting traditions of melody and harmony to create music performances in which every sound and every silence had an equal right to exist. Following Cage’s example, he tampered with the noble piano – or rather, he desecrated it – by rigging up all kinds of alternative noise makers to the keys and strings, until the entire construction resembled some kind of elaborate booby trap.

But while the piano was representative of an aged classical art tradition, it was the television – the cathode ray tube – that represented a future yet to be explored. And it was Paik’s deconstruction of this technology that truly made him a pioneer worthy of the name.

Except that… something strange has happened. In the mid-1960s, Paik’s work with TV was at the outermost reaches of artistic endeavour, somehow indicative of an art yet to come. But now, the clapped out wooden cabinets with their dusty bowl-like screens and space-race detailing look like anything but the icons of the future that they once were. Now they are junk shop curiosities, and the Great Global Events that we shared at home, crowding round the concave lens in order to passively receive signals from across the world, are now consumed in fragments of moments – edited, snipped and compressed to be snacked on while travelling, while gaming, while browsing. And when faced with the obsolete artefacts that represent Paik’s early career, that flickering future we imagined suddenly doesn’t feel like the future we’ve got.

Paik continued pushing boundaries until his death in 2006, and it would be erroneous to give the impression that this fascinating exhibition offers nothing more than technological relics. But having said that, it’s the image of those ancient televisions that stays with me, their single future-fixed eyes now blind.

It’s a sobering thought – as we click, swipe and stream our way through contemporary life, breezily believing that we’re co-opting the tools of the future today – that one day our flat screens, our tablets, our smartphones, our netbooks will be so much detritus. Let’s hope, at least, that our sense of engagement with the world isn’t shackled to our hardware, and that, like Nam June Paik, even as our slim, sleek, streamlined products begin gathering dust, we keep our minds locked firmly on the next step forward.

Text and images © Damon Fairclough 2011

Share this article

Follow me