Pinning down the past: a voyage around my badge collection

My beer mats went in the bin years ago. Most of my comics have long since decomposed. But my badges… they’re survivors. In this piece, I pluck examples at random from the hundreds in my collection, and submit them to scientific scrutiny by an expert. Namely, me.

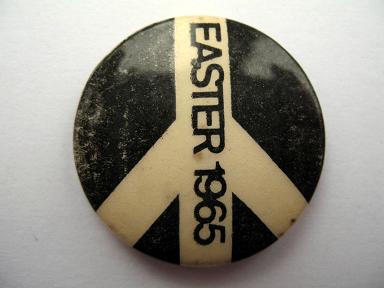

CND

Aldermaston March (1965)

“Ban the bomb” they used to say. It’s a phrase that makes me think of creaking intellectuals sitting in the road: Bertrand Russell, with overcoat and eagle-stern expression; earnest students in duffles and scarves. No Bono. No Coldplay. (The world may have been lacking in colour, but it wasn’t short of sense). It was pre-Pop non-conformity planned over coffee and jazz in some steam-fugged espresso bongo; concentration laced with condensation.

Things were not so duffled-up in ’65 I imagine. There was more than caffeine fuelling the fight, and world destruction was a nearly-was rather than a could-one-day-be – the Cuban crisis must have added a certain frisson to mid-1960s Aldermaston marching.

And somewhere my own mum and dad, walking together, and buying the badge (though probably not the T-shirt, the mug and the glossy souvenir programme, all of which may have been conspicuous by their absence). I imagine the march as a state of limbo, a stopping off point between a world of dusty Oxbridge dorms, cocoa, Joan Baez; and the world of just a few months later when Dylan went electric, students went hairy, and the Vietnam War just went crazy, man.

The precepts of protest were changed the world over. The vicars and conchies and Methodists and poets seemed to give up the ghost – or have the ghost taken from them; rare was the Church of England minister wielding Molotov cocktails. CND would have its time again in the era of Thatcher and Reagan, post-punk faux-funk, peace shops and nuclear-free zones – but for now, anti-war was coming to mean anti-Vietnam, anti-society, anti-walking around in a duffle coat with a Dave Brubeck LP.

For mum and dad, I suppose other things brought the march to an end. Having kids. Living in Sunderland. Being approximately skint. But there’s the badge, a memo from the past, a reminder of a more humble kind of protest – a kind that speaks to me more articulately than a self-righteous do-good-a-thon sponsored by Bacardi and Vodafone.

Hmmm.

From “Ban the bomb” to “Ban the Bono”. That, to me, sounds like progress.

—

Radio Sheffield

Promotional item (early 1970s)

Clearly, this dates from a golden age of freeform graphic design, when a major local radio station could knock out a badge – an item of official BBC merchandising no less – without regard for the rules of typography or aesthetics. Rigidly enforced corporate identity guidelines were some way off, obviously.

During this time, and for no reason I can now explain given that I was less than ten years old, Radio Sheffield was an under-the-covers listen of mine. From the daily morning news magazine show Edition One to the more relaxed tank-topped sounds of It’s Saturday! at the weekend, I sowed the seeds of my future love of conversation-based broadcasting; from this seemingly insignificant acorn, my many-ringed Radio 4 oak tree grew.

I’m sure that in Radio Sheffield’s early days – the time when, seemingly, a secretary on the front desk could be given paper and pens and asked to “do us a badge, love – for the roadshow” – it was innovative and pioneering, creating the special blend of warm-hearted parochialism that would define local non-commercial radio for years to come. Of course, having innovated and pioneered the style, it became an unchanging sonic tic that meant you could never mistake local radio for a national station ever.

So once I’d outgrown my naive affection for this curious sound world – yes, I became as authentically John-Peel-under-the-duvet as nature’s law dictates a man of my age should have been – Radio Sheffield meant one thing only.

And that thing was:

Snow.

During the Winter of Discontent – with its endless rounds of snow, strikes, snow, power cuts, snow, disco and snow – Radio Sheffield suddenly came into its own. As the white fluff fell from the sky, our family huddled round the breakfast table listening to inexpertly-tuned Radio Sheffield, praying to the pagan gods of industrial unrest and bad weather that our respective schools would be shut. It was a daily ritual during January and February 1979: a list of schools in alphabetical order, from Abbey Lane through to Yewlands; those who heard their school’s name intoned would inwardly punch the air, before planning a day of furious plastic bagging. (Being a kind of sledging fit for global recession: no expensive toboggan required. Just bring your bin liner and away you go!)

For parents: infuriating it was in that dawn to be alive (especially having been forced to swap Brian Redhead for Michael Cooke). But to be young, of course, was very heaven. The creeping sense of living in a disintegrating nation was masked – nay, obliterated – by freedom from study; though viewed more optimistically, we were learning valuable life skills. Via co-operation, we learnt to build snowmen. Via the weather forecast, we learnt about meteorology. And via the manipulation of our environment, we learnt how to hurl ice at some kid’s head.

And those days of wellied surrender to the forces of nature seemed to have been gifted to us – not by the local education authority, but by those cosy voices on the radio.

As the Winter of Discontent turned from reality into folk memory, and the possibility of nuclear confrontation loomed ever larger on our horizon, we surely felt a strange ache of comfort that should the four-minute warning sound, we would retune to Radio Sheffield and a homely voice would inform us that our school was closing. Perhaps forever.

Then, I’m sure, Tony Capstick would come on. To play some last requests.

—

Crucible Theatre, Sheffield

Promotional item (1970s)

In the flickering 16mm world of council-backed promotional film making circa 1970, there are certain civic projects that symbolise pride and post-war rebirth. And the common factor that binds them together – almost literally – is concrete. Ring roads; pedestrian precincts; tower blocks; civic centres: all share a rough-hewn lumpiness that once upon a time meant Not Edwardian, Not Twee, Not The Way Things Were.

Inter-city one-upmanship helped goad utopian-minded Aldermen and Mayors into projects both ambitious and impressive in scale: Birmingham’s Bullring; Manchester’s Piccadilly Plaza; Hyde Park, Kelvin and Park Hill flats in Sheffield. Those stout-bellied gents were generous and forward-thinking; I suspect that all along they knew they were providing work for the future architects, engineers and builders who would one day have to plan the renovation or destruction of their concrete offspring.

Mind you, the utopian ideals were real enough, whether thoroughly thought through or not. Polytechnics, comprehensive schools, concert halls and libraries were also being rendered in system-built, rain-stained 3D. It was an age of rates and public subsidy, and of theatre that was provided as a service rather than a pleasure.

Hence the Crucible Theatre, a new 1970s home for the forward-thinking Sheffield Repertory Company. Whereas their elderly proscenium-arched Playhouse venue had merely sufficed, they wanted a building that would usher in a new era of democratic performance, of unity between actor and audience. It was the right time to entertain such dreams; this anti-elitist, out-reaching way of thinking was what councillors wanted to hear. It was also the way that theatre was heading, and with the help of the bruising theatrical heavyweight Sir Tyrone Guthrie lending more than a hand, the Crucible was conceived, and built, and opened in 1971.

It was the 1960s and ’70s made solid. Theatres had been for dressing up, for being charming, for escapism and entertainment. The Crucible was for wandering into in the middle of the afternoon, for milling around, for thinking and ending up with an opinion. Vast, free-flowing, undefined space. A gaudy carpet. Concrete, of course. And always some children throwing themselves around. Jazz in the foyer, a recital in the Studio, Ibsen on the main stage. And rather symbolically, the rapidly-deteriorating Victorian Lyceum – by then, a bingo hall – still standing (just) about 20 feet away.

The Crucible was about refusing to compromise. There is no flexibility in its gigantic thrust stage. It is wide open and windswept, modelled on the classical spaces of ancient Greece. It doesn’t accommodate many touring shows, nor lend itself well to rock gigs. It was built for big themes, movement and imagination. With the audience sitting on seven of its eight sides, it imposes its own personality on the people who choose to work there, demanding thoughts that speak volumes.

The badge dates from the theatre’s early days – the large letter ‘C’ is the shape of the stage. Since then, those other grand projects – the fly-overs, precincts and tower blocks – have come to seem brutally misconceived. And while The Crucible has suffered from the harsh economics of 1960s civic construction – many are the buckets that have had to be employed there in rain-catching duties – it has so far refused to buckle to the revisionism that has seen its contemporaries bite the concrete dust. Quite the reverse in fact. Under a parade of artistic directors who have achieved varying degrees of success, it has taken on the spirit of the city; spectacular yet plain, and so very ugly-beautiful.

As I write, however, The Crucible is about to change. Its leaking public spaces will get a noughties makeover – an extensive one, I’m led to believe – and I suspect that edges will be smoothed, spaces replanned, ‘corporate hospitality’ made central in a manner inconceivable in 1971. I suppose it’s about time; ad hoc changes have diluted the original vision in any case, and I’m pleased to be assured that the main auditorium – designed by Tanya Moiseiwitsch – remains sacrosanct (though at some point in the 1980s, the stage’s shape was subtly refashioned – it is no longer quite the same as the ‘C’ on the badge).

But still, it feels like a compromise that maybe shouldn’t be made. In Leeds, the West Yorkshire Playhouse has achieved a fine reputation and theatrical success, but as a presence in the city, it looks exactly like a Tesco. It is early-1990s supermarket architecture; pragmatic rather than ideological. The Crucible, on the other hand, is an argument; it bellows “Concrete for all!”. It’s of its era – an era that had value if not necessarily a great eye for beauty – and I wonder if it still will be once the building work is done.

When the adjacent Lyceum was brought back to life in 1990, it was “restored to its Victorian splendour”, and no one would have suggested another way of doing it. So couldn’t The Crucible be returned to its pristine 1971 state, its concrete-and-breeze-block spaces purged of random kiosks, table clutter, stacked chairs? Because a theatre isn’t just about what happens on the stage. It’s about what its creators believed they were gifting to us; it’s about the building that blushed in muffled light on flickering 16mm celluloid, back when they told us Sheffield was a ‘City On The Move’. And we believed them.

—

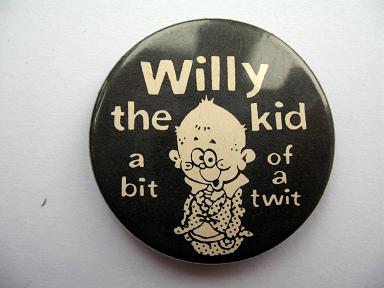

Willy the Kid

Promotional item (1978)

It’s in those cheeks, those eyes, the oyster-ears and the onion-head. It’s in the tautly fastened jacket and the dimpling bulges of cloth. It’s in the fact that the kid’s wearing a suit, shirt and tie – more than a hint of Just William in the guise of a 1970s comic character. Mischief, a ‘yuk yuk’ grin, a hare-brained scheme on the tip of his tongue.

And it’s in that word.

‘Twit’.

In all these things you can see the touch of Leo Baxendale, a comic artist – a children’s comic artist – who was the only one I knew by name, the one who went so far beyond what was strictly necessary on the page that every corner of every frame became a fresh landscape just pleading to be filled.

I first fell for the dough-faced drawings of Leo Baxendale when he created the Badtime Bedtime Storybooks in Monster Fun. These were pull-out centre pages that you snipped and folded into mini 8-page booklets entirely separate from the comic in which they came. The stories were corrupted fairy tales, classic adventures bent out of shape, twisted takes on worthy children’s writing down the ages. They were Baxendale cut free from the confines of character comics, at liberty to create a new world from scratch each week.

Not that such seemingly effortless invention came easy. In his book about the comics trade, A Very Funny Business, Baxendale details a plummet into nervous breakdown brought on by the relentless quipping, the slap-up feeds, the catapults and broken windows – the sheer operatic scale of his humorous invention.

So while Leo Baxendale’s Badtime Bedtime Storybooks were a childhood cultural highpoint, he jettisoned the responsibility sometime in the mid-1970s and disappeared from the pages of my Monster Fun, my Buster, my Whizzer And Chips. Not that he’d gone forever. In fact, he was planning an audacious return.

His scheme was to devote himself to a project of his own choosing, one that would involve working for a year on a single book. And that book was Willy The Kid. The first was published in 1976; it was followed by two more issues, in ’77 and ’78. Without the connection to an existing comic, Baxendale was able to conjure up his hero – Willy the Kid – and cram his world with friends, enemies, clockwork daleks, pet stick insects, sossie rolls galore. The drawings were large, the draughtsmanship just sublime. The books were – are – a reminder of what the world of weekly comics was losing, but nevertheless, they remain a fine and long-lasting keepsake from the dying days of pre-teenagerdom. My remaining comics are yellow, fragile and under the bed; most are gone for good. Whereas Willy The Kid is on the shelf where he’s always been, his pearls of Bash Street-esque wisdom a constant companion through times both black and white. And half-tone.

—

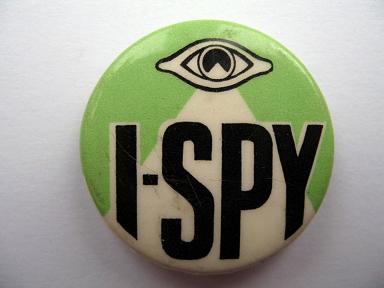

I-Spy

Membership badge (mid-1970s)

Sometimes, in the 1970s, you could feel the pull of another age.

Despite static-charged polyester outfits and flares unlimited, despite chemical puddings and chromatically-saturated TV, despite Scooby Doo Meets The Harlem Globetrotters and Tiswas, the whisper of the 1950s was still loud enough to be heard.

And we heard it, and we answered its call.

It urged us to join a pretend tribe of ‘redskins’, and dedicate our lives to observing things – road signs, flowers, architectural features, types of paving stone – before ticking these things off in a book. An I-Spy book. And having ticked a book’s worth of things – church spires, lollipop ladies, dry stone walls, double yellow lines – we could return the book to Big Chief I-Spy, who would stamp it with his official seal and award us an I-Spy Order of Merit.

All of this – the redskin shtick, the Sunday School vibe, the biscuits-and-orange-squash atmosphere – was like the death gasp of post-war austerity. “We don’t need things to have fun do we children? All we need is a pencil and some pluck. George… don’t do that.” And yet… like an Oxbridge don feeding secrets to Moscow, the buttered-crumpet ambience seemed to mask something more sinister…

Because the I-Spy Tribe felt like trainspotting’s revenge.

Having turned generations of mechanically-minded males into an anally-retentive breed apart, and been roundly ridiculed by wider society, it was as if the trainspotting virus had mutated into an altogether more virulent strain. Now everything had to be checked, ticked, catalogued. It was like being Jehovah’s personal assistant; an archivist to the gods.

And having recruited us into a super-observant youth movement with secret redskin ciphers and a pseudo-Masonic greeting, it then opened our eyes to an immense and eternal truth:

If we ticked something off in our I-Spy book – even though we’d never seen the thing we were claiming to have witnessed – no one would ever know!

Did Big Chief I-Spy have spotters on every street corner, monitoring our activities and reporting back to the Wigwam-by-the-Green?

No. He did not.

In short, you could lie through your teeth: you could tick off every type of church door, every barber’s shop pole, every policeman’s helmet, every sparrow, robin and crow you wanted. Big Chief I-Spy would have no choice but to award you an illicitly-earned I-Spy Order of Merit. There was nothing – nothing – to be gained by speaking the truth.

At that point, we left the 1950s and entered the ’70s for good.

And as if to prove that street-smart cynicism finally shoved aside all that was wholesome… can’t you see the threat in that menacing I-Spy eye?

Always watching. Always watching…

—

Little Chef

Promotional item (unknown date)

Before we begin, let me admit that it’s a love that defies logic. But then, love so often dares us to deny our rational selves. Distance, age, social class; these things can snuff out love as soon as the spark ignites, but when the fire is hottest, the flame burns on. And so it is with me and Little Chef.

The food is… not that nice. But don’t be so foolish as to imagine you would visit a venue like this just to savour the food. Because a stop-off at a Little Chef is about a break in a journey, a pause to consider the pleasures of a holiday to come. Or just past. An opportunity to immerse oneself in an approximation of an Edward Hopper stillness. (A rough approximation, it has to be said). (Very rough).

The quantity of fellow customers should be few. The time should be mid-afternoon. The ambience should be calm, restful, unhurried (and believe me, it will be). There is humped, manicured greenery beyond the window. There is a lone businessman a few tables away, lunching quietly to himself; thinking sales rep thoughts as he gazes into the middle distance; pink shirted, a little sweaty beneath the arms.

And you sit there and sip too-hot tea, contemplating the forthcoming fried delights: hash browns from the freezer, glistening eggs, skinheads on a raft. (See? The evocation of youthful holiday moments is so complete, my mind is already in Whoopee Summer Special mode: ‘skinheads on a raft’ = ‘beans on toast’). It’s an in-between world; in between roads and the car and a far-off destination. It doesn’t move and it seldom changes; once modern, now almost obsolete, it exists beyond the rules that govern the rest of your life.

How bad would the food have to be before I refused to step inside a Little Chef?

Truthfully?

Ahem. The answer is – very bad indeed.

They may trim the little logo-fellow’s stomach. They may slice off portions of the premises and turn them into knock-off Cafe Neros – a caffeine-fuelled search for a quick (Star)buck. They may protest that no-one loves the time they spend in their eternal-Wednesday-afternoon-on-an-A-road heaven, and one day they’ll vanish for good. Of course they will. But wherever there remains an off-road stop with acrylic curtains and snacks served in suspended animation, the spirit of the Little Chef will live on.

—

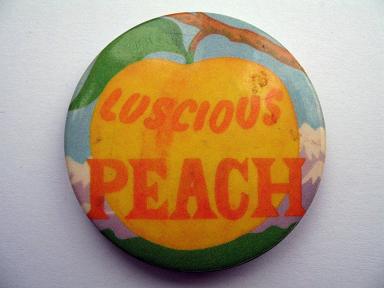

Luscious Peach

Origin unknown (early 1970s)

What is this?

An attempt by the Peach Marketing Board to claim dominion over the soft fruit kingdom?

A velvet-skinned version of ‘Finger lickin’ good’ or ‘Beanz meanz Heinz’ perhaps?

Or just a poetic thought to pin on your lapel? An appreciation of nature’s bountiful harvest, expressed with a hippyish stoner’s grin? “You can’t get anything more luscious than a peach maaan.”

I acquired it in 1974, and I like to think the latter explanation is the truth. Admittedly, this would make it troublesome to explain how it came to be in the possession of my great uncle – a man who loves toys, sweets, comics, TV, but who has never to my knowledge kept the company of flower children. For it was via him that it was passed on to me that summer; just a little something that a kid might like.

I did like it. I do like it. And now… I wonder if there’s more to that peach than meets the eye. Is it really just a pin-backed hymn to the prunus persica? Or does it speak of… fleshier delights?

Not something that troubled me aged seven, I must admit.

—

Sheffield City Museums

Promotional item (1970s)

A polar bear with its yellow teeth bared, a corked hole where it had been stuffed (and not “where it was shot” like your mates said).

Two Samurai wrestlers made of wood, faces grimacing, real hair decorating their taut-muscled legs.

A 3D tableau of back-yard creatures: mice, birds, a tattered fox; never moving, always the same.

Clocks: a corridor of ornate chronometers decorated with rising moons and setting suns, variously inlaid with silver and gold, many with moving figures – rather like shelf-bound versions of Trumpton’s Town Hall timepiece.

Knives and forks, of course. Enormous fan-like displays of cutlery, more boring than you could possibly imagine – at least to me, aged nine, or ten, or eleven, etc. Vast peacock tails of stainless steel and silver, all dedicated to the fine art of cutting up food and sticking it in your gob.

Sheffield City Museums taught me plenty about so many things: the hypnotic joy of repetition (every visit the same), the curious lifelessness of the taxidermist’s art, the fetishism of objects plucked from their context and annotated with typewritten cards. The curiosities were curated, though of course, they could only work with what they had – namely the whims and fancies of Victorian collectors – but as long as you weren’t longing to go outside for a game of football, you could hardly help but be blessed/cursed with a love of eclecticism and the pleasure of knowing exactly what lay round the corner. Bees in a glass-fronted hive; a shrivelled vole stuck in a milk bottle; an X-rayed mummy; those wrestlers; that polar bear. And so on, glass-cased and permanent.

They were something to look at. On drizzly Sunday afternoons, or during summer, as a prelude to a Lolly Gobble Choc Bomb by the band-stand in the park. They didn’t look formally educational but they were infinitely interesting, and in their own way they provoked a particular passion for objects (especially those chance encounters – sewing machines, umbrellas, operating tables – beloved of Surrealists).

And so ‘something to look at’ becomes ‘something to think about’ and ‘something to remember’. That’s how the museum worked for me and, no doubt, many others. There was a tiny sales desk – not a shop exactly, but somewhere you could buy, for instance, a museum badge with a picture of… erm… a barrel organ? There was no cafe. There was no interactivity – beyond walking, and looking. But really, there were worlds within worlds, and a quiet that was so profound, it actually made your ears ring.

—

Uncle Sam’s

Promotional item (1970s)

Firstly, you’re thinking, (I think), “Uncle Sam’s what?“

It’s Uncle Sam’s Chuck Wagon, of Ecclesall Road, Sheffield. An American-style burger restaurant of course, dating from the days of napalm and body bags, of Tricky Dicky, of Californian AOR rockers with their denim shirts, fat free-lovin’ ‘taches, and dusty motel stops in the sun-sinking early evening. Uncle Sam’s dates from those times, but as I write it’s still there, though the circumstances in which it exists are now rather different.

Once, for me, Uncle Sam’s meant Friday tea time. It meant ‘two franks in a basket’. It meant cold ice cream with hot fudge sauce. It meant Coke lamp-shades and a poster of a glistening black woman with revolutionary afro. And once, it meant the large tortilla ordered by my dad, which sat on his plate like a portion of Sydney Opera House, boggling my mind as to what it actually was.

You couldn’t get these things anywhere else in Sheffield. This wasn’t a limp Wimpy-style burger experience, with nylon-smocked waitresses and a whiff of post-war misery. This was teen girls in tight tees, flapping jeans as seen in UCLA campus riots, and an open kitchen in which strutting cooks laughed in the face of the REAL FLAMES that licked explosively at their faces. Forget the fact that we customers were of typical Sheffield suburban 1970s stock; we felt embraced by the spirit of the American age – of the space race and presidential corruption, of San Francisco bath houses and bankrupt New York, of The Towering Inferno and Kojak.

Uncle Sam’s was paper place mats printed with a star-spangled menu. It was a burger in a wicker basket. On Fridays and Saturdays, it was (GASP!) ‘open till midnight’! It was French fries, not chips. It certainly wasn’t gourmet grub, but neither was it Birds Eye.

I say ‘was’ all these things, because of course, its monopoly didn’t last long. It was soon joined by Yankees just a few hundred yards away, and any number of other establishments that were either slightly more up market, or a little more down, or by the end of the decade, a different kettle of McFish entirely. So the Uncle Sam’s that now exists in the same spot on Ecclesall Road is not so special; but during the young years of the 1970s, when no one you knew had ever been to America, it was like a journey to the States (without leaving a carbon footprint as large as Robert Wadlow’s).

Strange, then, that the first and (so far) only time I have witnessed an afro-haired black woman say “Sure thing” in response to my dad’s request for a new fork, it was in the formica-tabled, ketchup encrusted Golden Egg.

How did you let her get away, Uncle Sam’s?!

—

Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire

Propaganda item (early 1980s)

To some it was an insult. To others it was a badge of pride. To most, it was just about refusing to give Thatcher an inch, and if you could do that by pretending your beery, sandwichy local council was akin to the Paris Commune, so be it.

Apparently, the phrase ‘Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire’ was first coined by Irvine Patnick around 1980, for years the only Sheffield Tory you could actually remember by name. He meant it as abuse, of course, but there were plenty of socialists in the city who thought that while Maggie ruled Britain, we could at least make it known that we had no part in her victory. And that was undoubtedly true; there was just one Conservative constituency in the whole of South Yorkshire, and this during a time of ideological, evangelical Tory domination. To the people who came round our house for left-wing banter, ‘Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire’ sounded actually rather splendid: so quick, get out the badge making machine.

In 1980, the steel industry was being put to the (Sheffield made) sword, of course, and the most socialist thing the council could have done would have been to urge those workers to political and social revolution. Of which, no chance. Still, in the early 1980s of an emasculated Labour Party, you could signify your socialism in other ways.

So Sheffield became a natural home for CND’s annual conference. The council helped find a home for the National Union of Mineworkers, guaranteeing the city a starring role in the 1984-85 strike; BBC reporters treated the place like a war zone from which their correspondents might never return. The locally-raised rates were shovelled into public transport subsidies, arts centres, peace shops. A few quid was found for a red flag, which was then unfurled above the Town Hall on May Day. We were twinned with Donetsk in the Soviet Union and Esteli in Nicaragua. And no vaguely left-wing festival anywhere in the world was complete without a visit from Sheffield Socialist Choir.

And as if to prove that Soviet-style bureaucracy wasn’t the worst thing that our democratically-elected representatives could think of, they launched a council-funded recording studio and called it… Red Tape.

Beloved of tabloid headline writers, behated of tabloid editorial writers, Sheffield was ‘loony left’ without the entryist abandon of Militant’s Liverpool or the metropolitan swagger of Ken Livingstone’s GLC.

In Sheffield, we were more famous for bus fairs that cost two pence.

And when our cheap fares went the way of the trolley bus and the horse-drawn carriage, you knew that our socialist republic was beaten.

Only to be preserved in pin-backed metal and plastic; a fitting memorial to those badge-happy, confrontational times.

—

The Jam

Promotional item (1979)

I really don’t think Paul Weller would approve. The artful mod stylist – the leader of the Italo-casual Style Council – would not look benevolently on a vast prismatic badge, at least two and a half inches across, spangling in the light like New Wave diamante. Neither, I suspect, would he crack a smile at the graphic literalism that links the band with a pot of strawberry conserve.

But I cared not a jot. I barely knew a track by The Jam when I bought this badge, never mind being familiar with the obsessively trim sartorial traditions into which Weller had self-consciously slipped his band; and when I later learned what mod actually was, I was confused by The Jam’s overt connection to that neat and buttoned-down modus operandi. In the slip-stream of Two Tone, the mods of 1979 were claiming The Jam as one of their own; but to me, entering Bradley’s Records with the expressed intention of buying a musically-themed badge, they were just one more punk name with which I could align myself in the school yard. I wanted to be a kid no more; I wanted to be known for a love of music, and I needed to show that I meant business in the field of pop culture.

So, standing in Bradley’s in 1979, with pocket money that was ring-fenced for badge buying, I selected the one that looked the most ‘pop’ and offered the best value for my 25p. Not for me the tiny, tasteful ‘buttons’ that clutched discreetly to your lapel. I wanted glitz, glamour and a huge surface area, with words that no one could ignore.

Funny that it was buying a badge, not buying a record, that marked the onset of a lifelong lust for music. The first step was to join the club, be one of the gang; the next step was to acquire the taste for black vinyl.

First King Rocker by Generation X. Then a K-Tel new wave compilation. Then more Generation X – the album Valley of the Dolls. And so it went on, and still does. But I realise now that despite the not inconsiderable chest-based real-estate I devoted to them in the form of this badge, I never ended up buying any music by The Jam. To this day I own nothing by them – not a CD, not a record, not an MP3 file (legal or otherwise).

All in all, I don’t think Paul Weller can have bought many pairs of winklepickers with the proceeds of my less-than-frenzied passion. This badge was a mere flag of convenience, a signal to schoolmates that I was about to begin disowning childhood and was ready for pop’s sweet embrace. Unfortunately it also dazzled teachers and made my school jumper sag; but for a while I wore it proudly, flashing a pretend allegiance that was enough to open the borders to the future; where as you know, they do things quite differently.

—

Preparing for Power 1984: Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP)

Propaganda item (1984)

There she stands, red flag aloft; her pennant being the international symbol of proletarian brotherhood and of being pitched headlong into London’s bubbling mid-80s revolutionary cauldron, aged 17 (just). I was heading for a Marxist summer school called Preparing For Power, run by the Revolutionary Communist Party, and in the time it took a coach to drive from Paternoster Row in Sheffield to the Polytechnic of Central London, that scarlet banner was transformed in my mind from an abstract representation of left-wing ideology into my own personal heraldry… though heralding what?

Well that’s easy: independence from home; contrariness of spirit; and a rubber-necking fascination with physical street-based conflict, be it Miners v. Police or Irish v. Brits. Whatever the cause of that thrilling political punch-up, I wanted in. And in London in 1984, I found the entrance.

When I stepped off that coach without family or school friends around me, just newly formed comrades by my side, I felt the very breath whipped from under my nose and I struggled to remain standing. It wasn’t the city itself that took my breath away – I was already well used to visiting London for art and for sight-seeing. It was this particular wind-tunnel of a London in which left-wing activists and associated big-mouths seemed able to talk up a hurricane of argument and invective – or more accurately, any number of individual whirlwinds that blew against each other, with each other, and that merged, split and devoured each other.

I had come from Sheffield – home of the National Union of Mineworkers, surrounded by militant coalfields – in the eye of the miners’ strike storm. But suddenly, Sheffield seemed like a calm place. Because this was where the tumult was, where every opinion had its magazine and someone to sell it. Sparts, Workers’ Power, RCG, WRP… it was bewildering, a sweet shop of sugared left-wing sects shaking themselves off the shelf. It was an excitement I could taste; I was terrified of it, but oh so tempted.

Alas, I realise now, the calm that I sensed back in Sheffield was simply the soundless cry of the desperate, of the families whose communities were no longer known to them, controlled as they were by police with shields and their ID numbers covered up. Those people were rapidly running out of options, and could only face their tormentors with arms outstretched, or faces smothered, like Munch’s silent scream.

This London storm merely whipped across the surface of everything, creating havoc and yet disturbing nothing. No one was crying out in pain down here, but it was a wind in which I was caught, and I flapped and tumbled and bowled down that street, through the door at Preparing For Power, and into the heart of my own revolution.

—

Sheffield City Morris Men

Promotional item (circa 1980)

Not so much a morris dancing troupe as an anarcho-communist gang in knee-breeches, Sheffield City Morris Men prowled the wind-blown concrete acres of my late-1970s youth; their natural habitat circa 1978 was a flagstoned pedestrian precinct thronged by shoppers agog.

The shoppers would form an undulating mob, ringed around this riotous assembly of hirsute lecturers, teachers, a few mature students; the dancing was muscular, expressive, and at times, frankly, intimidating. The wheeze of their melodeon joined the chudder of the internal combustion engine and the plaintive cry of the left-wing paper seller as my recurring Saturday afternoon soundtrack; and once the dancing was done, we would decamp to the enveloping hug of a public house, savouring the guff of fags, ale and sweat that billowed out as we opened the door.

There can be few nine year-olds as familiar with the insides of pubs as the nomadic offspring of morris dancers.

At which point, it seems, the truth is out:

I am indeed The Son of a Morris Dancer.

This badge was designed by my dad, apparently as a self-portrait – that was the jibe at the time anyway, as the bearded hankie-twiddler captured thereon bears an uncanny resemblance to dad in mid-caper. Though to be fair, give or take a few tweaks round the mid-riff, it could have been pretty much any of them. Because yes, they all sported the necessary decorations of the 1970s folk revival: beards (damp with the foam of freshly pulled cask ale), Citroëns (elderly, and festooned with stickers), hands cupped round ears as they broke into another chorus of Dido, Bendigo (“Gentry he was there-o…”).

But don’t be misled; these were morris dancers with a difference. Creators of their own made-up tradition – or ‘Meddup’, as they called it, in deference to the Sheffield dialect and in defiance of the hermetically-sealed and sterile world of The Morris Ring (like the Rosicrucian Order… but with bells on), they made it their business to jump higher, play louder, hit harder.

While my friends had misbehaving rock stars as their anti-heroes of choice, my bad role models were morris dancers doing things my parents never did: puking pure red wine on a coach to Brittany; forever bed-hopping, trailing divorces in their wake; singing paeans to Stalin’s five-year plan; lending me records by Ian Dury, X-Ray Spex, John Cooper Clarke.

Formative experiences all. So although I ultimately spurned the lure of the flailed handkerchief, their spirit made my heart beat like a tabor.

An abiding memory: walking through York on a blazing weekend having danced in front of the Minster (always the year’s most financially lucrative display), my dad and his pals are done up in their baldricks, their beards, their bells; replaying the scene now, I picture a righteous slow-mo swagger – like Reservoir Dogs but with a little more jangle. We pass through a busy precinct, where Doc Martened, Fred Perried fascists are dispensing magazines on behalf of the British Movement. They look harder than any men I have ever seen in my life. And as we pass, one of them thrusts his papers towards my dad.

Dad breaks stride, and in his knee-length breeches, with handkerchiefs slung at his waist, he looks the fascist in the eye and says, “You must be joking sunshine.”

And we move on.

I gulp, tremble and shiver with pride. For when you walk with Sheffield City Morris, truly, you walk with lions. (And a fat man dressed as a horse.)

—

Clothkits

Promotional item (1970s)

Here it comes! It’s the Sign of the Rusting Dove™, bringing glad tidings of peace and love direct from somewhere over the 1960s’ rainbow, and in its beak it carries… what? Recreational drugs? Copies of Oz? A stack of Incredible String Band LPs?

Nope. As you can see, our Rusting Dove™ is a messenger for Clothkits, supplier of screenprinted textile fashions to the children of the counter-culture. So inside that brown paper package tied up with string we find the constituent parts of dresses, trousers, T-shirts and hats – but don’t get excited, because no one’s going anywhere just yet. These are not clothes as anyone born after 1988 – when Clothkits closed – would recognise them. These are vast expanses of patterned fabric printed with dotted lines and a few instructions – it requires the application of scissors, thread and one of Singer’s finest before we’re wearing this gear down at the play scheme.

But believe me, regardless of the fact that there was hard work involved in bringing the clothes to life, that Clothkits kit schtick was popular. Their catalogue was the house journal of Britain’s leafy urban enclaves, and when we got together – all us kids in our Clothkits clobber, maroon and navy, stencilled like a tea chest – it was like baby bohemia on the march; with our liquorice root and our screenprinted corduroy, we would one day claim those artfully scuffed Victorian villas as our birthright.

Though if that Rusting Dove™ should come a-calling these days, it can take its box of fabric and come back when the clothes are in one piece, thank you very much.

—

Aswad

Promotional item (1984)

Maybe this isn’t official Aswad memorabilia at all – it doesn’t feature their name or image, as you can see. It features, of course, the red, the gold and the green; the colours of Rastafarianism, as worn by the followers of His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, King of Kings and Elect of God. And so, given the colours’ spiritual significance – as Rasta as dreadlocks and the holy herb itself – it was an irony typical of the times that upon attending a gig by Aswad at the Sheffield Top Rank in 1984, I should buy a badge bedecked in those glorious hues – me being a wide-eyed middle-class white atheist who’d told his mum he was going with his mates but who had, in fact, gone alone.

Clearly, it was a possibly-misguided appropriation of someone else’s signs and symbols, but there was nothing false about my devotion to Aswad’s sound. To many, they will be remembered only as sugared pop reggae thanks to their 1988 hit Don’t Turn Around, but earlier in the decade they had been purveyors of a myriad of reggae styles – righteous roots, silken lovers’ and crisp live dub – all delivered by a band that played tightly, militantly, yet who were unashamed of pleasing the crowd.

And please crowds they did. For years they crowned the Notting Hill Carnival with joyous black-British reggae that was a stirring-up of Jamaica with Ladbroke Grove and Brixton – though not Carterknowle, or Millhouses, or the other leafy Sheffield suburbs I called home, please note. Not that it mattered; while I had never been to the Carnival in person, I had listened to Aswad’s Live And Direct on cassette – over and over and over again. And even via the medium of a tinny Panasonic tape deck, that recording of their 1983 Carnival performance carried a ‘being there’ quality that no other live album I know can capture. Simply, it is magnificent. And every chk and every thud, every rumble and every scream, floats on an atmosphere of sweaty London streets, kids on shoulders, ganja mist and steel bands, and of course, coppers in shirt-sleeves dancing with semi-naked black girls for the cameras.

So that was the spirit I took with me into the darkness of the Sheffield Top Rank, where I waited and waited for Aswad to appear. I’d implied to my mum that a bunch of us were going, but in fact my reggae was a rather personal pleasure and I ended up going by myself. Too aware of being under-age to buy a drink, I just stood in the gloom and learned how those kinds of gigs worked; I soon realised the band would not be on at 8pm, or even 9pm, or 10pm. This was a late-night experience, and I would be pushing it to reach the crazy hubbub of the 1.30am bus home from High Street; in fact, I had to leave before the end of the tumultuous encore, simply because my carriage awaited.

But of course, the waiting was perfect. Because by the time they appeared, it felt as though I’d waited all my life. My emotion wasn’t just pent up; it had been dammed for a decade and a half. How different to those sullen guitar bands whose audiences stand with beers, looking forward to the moment they finish. Suddenly, I realised what communal music could be – and I don’t think I experienced it again until the unhinged days of rave.

Why not try it for yourself? With just a few clicks you can buy Live And Direct and feel the power of Aswad, 1983 vintage. The drum and the bassline, the Aswad horn section, the dummy reverb and the chanting down Babylon: “How about a different style?” screams Brinsley Forde, and Aswad switch yet again, one moment lilting, the next moment all blood, fire and Jah.

It was pure showmanship, or maybe some kind of Rasta magic. But supernatural or not, this badge is a relic of the night I saw them; a remnant from a lesson in reggae that stays with me still.

—

Airfix Modellers’ Club

Membership badge (1970s)

I look at this badge now and I imagine a draughty church hall, a kindly vicar dispensing barley water; boys in knitted, roll-necked zip-up cardigans; hair oiled and pressed, and parted at the side – or short-back-and-sided, with a dry tangle of curls bursting from the top of the head. There are trestle tables arranged down the centre of the hall, scattered with Lilliputian military aircraft in varying states of construction. And though these boys are glue sniffers all, their addiction is a passive one: an incidental ingestion of aromatic plastic cement is all they crave.

For they are Airfix modellers, transfixed by their craft. Silently, they paint the parts of their plastic aircraft before glueing them together (as recommended in the directions – a rule routinely flouted by rougher boys looking for instant gratification, who throw their planes together then give them a hurried lick of colour – a quick Airfix, if you will). Patiently, they float decals in a saucer of water, gently skimming them from the surface with a skilled finger and laying them in their allotted location – set-square straight. And as they apply those finishing touches, each model is allotted its place in a spectacular bedroom display, perhaps in some kind of elaborate ceiling-suspended dogfight tableau; to be glinted at by light that pierces cracks between curtains; to be shrouded as the night falls; to be dreamt about by boys with The Eagle under their pillow.

An enduring image, I’m sure you’ll agree. Except that my membership of the Airfix Modellers’ Club didn’t involve me in any such wholesome ritual. It didn’t really exist as a club; it was just a marketing wheeze that allowed Airfix to claim some real estate within the pages of then-popular comics, and as a serial joiner, I clipped the form from a page of Buster, filled in my name and address, and returned it accompanied by a stamped addressed envelope. The fruits of membership were the badge (above), a glossy gilt-edged certificate, and a welcoming letter signed by none other than the club president himself – TV’s very own Dick Emery. His gurning fizzog served as mast-head on the club’s page in the comic, and was no doubt meant to engender a frisson of show biz excitement next time we perused the packs of deconstructed fighters, bombers and aircraft carriers in our local hobby shop.

Dick Emery: a curious choice for president, it has to be said. Was he a performer famed for his deft ways with a craft knife and a can of Humbrol enamel? Did he yearn to return to polystyrene fantasies even as he dressed up as that flouncy blonde who always said, “Ooh, you are awful, but I like you”? As a child raised on 1970s TV, I was certainly fascinated by his grotesqueries – his randy vicars and busty harridans – but he also seemed… illicit. He shared the same airspace as Benny Hill, Carry On, and other era-defining fare that involved much chortling over the word ‘crumpet’. His show existed in a world of dirty weekends, of mucky books, of big knickers on washing lines and Peeping Toms on the other side of the garden wall, and consequently he seems ill-judged as the representative of a British toy brand in the tradition of Hornby, Meccano and Matchbox.

Although, now I think about it…

Sticky bedrooms; clammy palms; curious urges zipped up and tucked in…

Perhaps not such a mismatch after all.

Anyway, it’s a good job we members weren’t required to demonstrate our modelling prowess. For in truth, I would never have passed the entrance exam, given that I perhaps made four, or maybe five Airfix models in my entire childhood career: a few glue-smeared planes, and a far-too-ambitious Bentley car – an inappropriate Christmas present that stretched my abilities and patience far beyond breaking point.

“As likely as a tornado tearing through a scrap yard and throwing together a jumbo jet,” say creationists when they hope to discredit Darwinian theories of evolution. My Airfix Bentley, on the other hand, was exactly what you would expect such a whirlwind to create – a random-looking pile of engine parts, tyres, exhaust pipes and headlamps. And caked in dust, it stood on my shelf, symbolising my lack of intelligent design skills; had I had to bid for modellers’ club membership, I would certainly have been naturally selected straight out of that gene pool.

So while I still own the badge, I no longer own the Bentley. Or the Spitfire, or the Hurricane, or the Harrier Jump Jet.

I’m sorry Mr Emery.

Erm… membership rescinded?

—

Brian Deane: Sheffield United FC

Fans’ badge (1991)

Here we have, in Fimo form, the footballer Brian Deane, one of the Sheffield United players most revered since the long gone days of Tony Currie, Billy Dearden, scarves round wrists and the Stanley-knifed football specials. Brian Deane’s days at Bramall Lane are also now long gone of course. However, between 1988 and 1993, he was our spindle-driven goal machine, all elbows and knees and a teetering gait that seemed to threaten perpetual overbalancing. Except that, in the words of local sports reporters, he was “surprisingly skilful for a big man” – and in any case, aesthetic ungainliness was not something that gave a manager like Dave Bassett sleepless nights. What counted were the goals: and what a lot we got.

For two cataclysmic seasons, Sheffield United hurled themselves headlong at the top division of English football. At times it seemed as though they could just batter their way in, with ball after ball flying off the end of Deane’s foot into the net as the team clattered its way through successive promotions. With Tony Agana (“silky and dangerous” – © Tony Pritchett of the Sheffield Star) alongside him, Deane was our long-limbed figurehead; a brace here, a hat-trick there, and always the prospect of more to come. Hence our own Blades’ Banana Boat Song:

“Deeeano!

Deeeeeenooo!

We want goals and we want some now!

Not one, not two, not three, not four,

We want goals and we want some now!”

Except… try telling all that to football fans today, and they won’t believe you. Those who are old enough seem to have erased the fears that the names Agana and Deane once stirred in them; though the fears were real enough at the time, and I have the newspaper cuttings to prove it. And those who remember the Brian Deane of subsequent years – at Leeds, Benfica, Middlesbrough, Leicester, West Ham and Sunderland, not to mention two more spells for the Blades – seem to have reimagined him as a braying donkey of a player, nodding in lucky goals from balls sent heftily, hopefully high.

So this badge remains to remind us that we weren’t deluded souls pinning our hopes on a saviour who could never deliver us from lower division limbo. He was, in fact, The Real Thing: he led us, and we followed, and we entered the first division’s promised land in 1990. And honestly, we weren’t fools; we knew a heroic but hopeless donkey when we saw one, and we had plenty; we praised them too and turned them into inexplicable cults (yes, I’m thinking of you Bob Booker), but Brian Deane was not of their ilk. When we were about to see him play, we said grace – a very awkward kind of grace, befitting his off-centred lope – and for his gifts we were truly thankful.

And now… a word on that yellow shirt. That was United’s away kit from 1989 until 1991 – an acidic shade of fluorescent yellow that mimicked the high-viz jackets worn by football ground stewards; if you squinted just a little, it seemed as though we had a team of 50 at least, ringing the pitch and threatening 360 degrees of sporting devastation. The word on the terraces – and they still were terraces – was that it was Umbro’s biggest selling away kit: I can’t vouch for the truth of that, but wherever you went on your sun-seeking package hols, the beach would be dot-to-dotted with citric splashes of yellow-green ultraviolet-bothering light; you could always find the Blades abroad.

Ridiculed by opposing fans as rampantly tasteless, those shirts seemed to embody a ‘no-one-likes-us-but-we-don’t-care’ spirit that came with the territory when your manager was Dave-Bassett-ex-of-Wimbledon. They loathed our yellow away kit, and they fantasised that our goal-crazy striker was a talent-free liability.

Ah, bollocks to them.

It might be a little bit unflattering, and just possibly even a little bit racist, but this badge says that Deano was one of our greats. That’s, our greats.

Not yours.

—

Fred Jowett: Bradford Independent Labour Party

Election badge (circa 1928)

You don’t know this man, though my granny would have recognised him in an instant.

A century ago, every citizen of Bradford knew him too.

And I know him – after a fashion.

He is the Right Honourable Fred Jowett MP, Member of Parliament for East Bradford – I believe this badge dates from the 1929 general election. He was my granny’s uncle, and therefore my great great uncle: that seems very far removed, but even while I played as a child, he lived on as the subject of reminiscence – though by then he was thirty years dead.

In fact, he lived on in other ways too: in the concept of free school meals; in the defiance of war; in Bradford’s tradition of non-conformity and dignified support for working men and women – a stone-chapel socialism conjured not from blood-drenched barricades, but from Sunday walks under soot-cloudy skies.

He was known by Great Men of his age. By Keir Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald of course; by Fenner Brockway, who in 1946 wrote a book – Socialism Over Sixty Years: The Life of Jowett of Bradford; by J.B. Priestley, the great writer and broadcaster, who gave his name to a Bradford theatre, the Priestley Centre – which stands on the site of a building once called Jowett Hall.

But his name travelled further still. Far beyond the temperance bars and Sunday schools and auto-didactic endeavour of buttoned-up radical Bradford, he was known too by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, who in 1912 discussed recent events at the Independent Labour Party conference in Merthyr Tydfil. ‘Opportunists’ in the party wanted to support the Liberal government against the Conservatives. Fred Jowett, on the other hand, moved a motion to reject this plan. He wanted his party to remain as its name suggested it should be: independent. If that meant victory for the Conservatives, then so be it. His party would still be a ‘labour’ party in more than just name.

Lenin wrote:

“Jowett’s motion took the bull by the horns… The opportunists, who predominate in the party, immediately attacked Jowett…

…The opponents of opportunism acted far more correctly than their like-minded colleagues in Germany frequently do when they defend rotten compromises with the opportunists. The fact that they came out openly with their resolution gave rise to an extremely important debate on principles, and this debate will have a very strong effect on the British working class.”

This, in its own way, was a glowing tribute to Fred Jowett. The two men were from left wing traditions that were as different as could be; they could scarcely have agreed on much with regard to the elusive road to socialism – it is impossible to imagine a relative of my gentle grandmother taking command of a workers’ army and defending the deeds of a bloody revolution – but from the famous to the almost forgotten, there is respect for a principled stand.

So am I wrong to think that granny’s tender ways maybe mirrored those of her much admired uncle? Could he really have faced down those ‘opportunists’, denounced war after popular war, or presented himself time and again for possible rejection by the city’s electorate if he was as kindly and mild as I imagine him to be?

Well, there’s no reason to doubt it. In 1906, Fred Jowett was described thus:

“This quiet-voiced, slightly-built, demurely-dressed (grey and black tie, starched collar), pale young man, with smooth black hair, correctly parted. Why – I told myself – he might have been a college student preparing for the Nonconformist ministry!”

A hushed presence; morality built from millstone grit. That’s what Bradford makes me think of. Small people with colossal thoughts, creating futures that others could take for granted… and for their trouble, becoming memory, then becoming nothing at all.

Fred Jowett is not the only one. There are always many like him.

Not giants.

But we stand on their shoulders just the same.

—

Dead Kennedys

Promotional item (early 1980s)

Flailing and venomous, they came screaming by; and in those brief moments of noise and dread, the Dead Kennedys were ciphers for things that I never suspected. A president had his head demolished in order that they should be so named; the West Coast scene from which they sprang was fired by a muscle-bound political viciousness that was focused and motivated; the language they used wasn’t subtly ironic – it was sarcasm wielded as brutally as a nightstick. “I kill children” indeed.

These things were all but lost on me, but to my dad – always interested in the music I professed to like, and intrigued by punk as a social phenomenon, or as a new folk music – here was cause for alarm.

This was not like The Damned, who were feathered and boa-ed with the spirit of the music hall, and who were just a mouthful of gob away from being suitable guests on The Good Old Days. This was a world apart from The Stranglers, whose Hammond-driven pub rock and real-life cartoon capers threatened no one except the odd smart alec music scribe. And despite “You dirty fucker” and the rest of that Bill Grundy pantomime, even the Sex Pistols turned out to be more art school prank than sedition made flesh. Nothing wrong with art school pranks of course, but they don’t chill the parental blood quite like the DKs hollering “This world brings me dowwwwwn, I’m looking forward to death.”

When I played the Dead Kennedys, I heard a sound that was scabrous and incandescent, that scorched the teak-effect music centre from whence it came. What I didn’t discern though, was the fact that this music, these songs, were born from a seething spirit of discontent that found delicious thrills in confrontation – meaning real confrontation; without fear, and with hatred unbound. A decade and a half previously, it was this spirit that had made gun-runners out of bedroom fodder – the kids who would otherwise have spent their time with headphones clamped to their, er, heads. Once begun, the journey that this music could take you on had no prescribed end; it could inspire belief in ‘all means necessary’; it meant no room for argument, no compromise, no fuckn waaaaaaaaaaay!

There was also so much cloaked meaning behind those furied Semtex-powered guitars that it could all be taken any number of ways. The confusion was such that the Dead Kennedys were later obliged to release one song that said what it meant from first chord to last: Nazi Punks Fuck Off.

If a bunch of comedic fez-wearers like Madness could find themselves with their own fascist following, for the Dead Kennedys there was surely no chance of escape.

So when I brought home the Dead Kennedys album Fresh Fruit For Rotting Vegetables, there was much furrowing of brows and hovering in doorways. There was earnest stroking of chins. There were sudden and serious conversations that seemed to come out of nowhere – about songs that said one thing and meant something else, about discussion and argument, about nihilism and protest, about Jello Biafra’s visions of AmeriKKKa. I believe there were whispered discussions when I’d gone to bed, undertakings to “keep an eye on this” and to be watchful, wary of some threat left unspecified but that could tip me into future oblivion.

Still, if it was felt I was heading for some kind of political and moral meltdown as a result of being seduced by this music (and while I think I was more or less saved from such a fate, I do recall wantonly startling babysitters by playing California Uber Alles at extreme volume), there were other parents who took a rather different view…

In the autumn of 1980, a school friend of mine returned from the summer break somewhat translated. His hair was cropped spikily short; his natural blond locks were streaked vivid orange; he wore a stud in his ear; his school trousers were calf-clingingly tight. With famously wayward siblings and a gig-going mum and dad, he was only pursuing the family tradition, but to the rest of us, his was a lead we wanted to follow.

This fresh-faced junior punk would bring back reports from his family home, though to us, they may as well have been coming from another universe: his parents owned Never Mind The Bollocks; his sister had dyed her pubes green; and then came the news that, aged 13, he was going to a gig at the Sheffield Leadmill; he was going to see the Dead Kennedys; HE WAS GOING WITH HIS FUCKING MUM AND DAD!

They weren’t there to chaperone him, or monitor his activities, or warn him of the dangerous paths that might lie ahead.

No.

They were there to see the band. That’s all. To see the band and spend some time with their son.

In the middle of an aural inferno.

It was, in effect, a gob-flecked family picnic; somewhere to take the kids; a nice evening out – like going to the panto.

And that same year, our family went to see The City Waites – a medieval music ensemble with songs called Pox On You For A Fop. Rather than songs called Kill The Poor.

Which went to prove little, except that, in the words of teenagers everywhere: life was so unfair.

—

Greetings from Sheffield

Promotional item (circa 2003)

Greetings…

From the name on the knife blade. From the place where you once changed trains. From Orgreave. From Hillsborough. From names that hollow the soul.

From the Sheffield Pensioners’ Liberation Army Faction. From Betty Spital. From Bobby Knutt. From the papier-mâché pages of a wet Sheffield Star, shoved through the letter box and soaked grey by the rain. From Praise And Grumble. From Capstick Comes Home. From beer offs. From Walsh’s. From Redgates. From Cole’s.

From the ether. From the static. From the ever-fading pirate chatter (“Shout going out to the Firth Park Crew – watch your bass bins Sheffield”). From the Socialist Choir and the Fuck City Shitters. From the Flexible Penguins and Trolley Dog Shag.

From rooms above pubs, 50p on the door. From Hattersley. From Furnival. From Mappin and Graves. From Henry’s and Cairo’s. From the Leadmill, from Stars.

From the Boxing Day Massacre. From the Sheffield Show. From ‘Fresh as tomorrow’. From the hole in the road. From the Green ‘Un, the Brown Cow, from the workers’ flag. From Caborn Corner to the Town Hall steps. From banners, from stirrings, from placards, from speeches.

From Angel Street, and West Street, and signing on. And on and on.

From Looks and Smiles. From waged/unwaged. From the night bus on High Street. From the 1pm whistle. From fingerless gloves and jumble sale coats. From Henderson’s with everything. From Whitbread and Wards. From the Anvil, from Pond Street, from ‘El off’ and ‘FON.’

From staring at the horizon from bus stops: from the 59, the 17, the 24 and the 76. From top decks fag-butt littered, smoked like a kipper. From “Brian Deane and Tony Agana, bibbidy bobbedy boo”. From the Owls, from the Blades… and from the pigs. From the biggest village in England, the one with summat to prove.

Greetings from Sheffield, from a drizzling there and then: England’s fourth largest, Yorkshire-But-Not.

Greetings from Sheffield: out on its own, twinned with Bigger-Than-You-Think, and nowt to do with Leeds.

Greetings from Sheffield.

Greetings… from eternity…

…back to here.

—

People’s March for Jobs

Propaganda badge (1981)

Cars burning; police running; men dying. It wasn’t the People’s March For Jobs that caused events like these; but that was the context in which this latter-day Jarrow Crusade took place. We were two years into Mrs Thatcher’s reign. In April, the streets of Brixton had been in flames; to most they were riots, to some they were rebellions, though what they were is a discussion for another time. That they happened at all was enough to tell me that some people weren’t satisfied with something; and I doubted that they were demanding a fourth TV channel or more use of synthesisers in the charts.

More dissatisfaction came in May: the People’s March itself. Here was mass protest that looked all the more polite thanks to the scale of the violence that enclosed it. It was just people walking, that’s all; from Liverpool to London, a core of 500 of the new unemployed making their way down Britain, and being joined by thousands more at every town and city they visited. By all accounts it was festive and even fun, entirely lacking the sense of approaching death that had tailed their ragged-trousered forebears, those hunger marchers of the 1930s.

But hunger did still stalk the streets in May ’81; just not the streets where these marchers chose to tread. In the cells of the H-blocks, where Irish Republican prisoners were striving to reinstate the privileges of political status that the British government had taken away, they were dying of hunger. Their self-summoned starvation passed across our TV screens like a Biblical phantom and we couldn’t look away. It was horrific and irresistible; alien and strange. They faded until their shadows consumed them, yet still we came to know their faces, smiling out from photographs taken when they were just young men with something to prove. Round, solid, real young men; whose deaths meant more of that fighting on the streets.

As time passes we parcel these things separately in our minds, and it’s hard to remember how they must once have run together: first Brixton, then on 1 May the march began, and on 5 May came the death of Bobby Sands. More hunger strikers died, the streets burning every time; and the people’s marchers snaked through the month towards their benefit gig in Brockwell Park – and no tea with Mrs T, who refused to meet them.

Ends of tethers; varying degrees of desperation. It was the way she chose to do things, that Prime Minister who seemed constantly at war. Because May 1981 wasn’t an aberration; it had become more or less the norm. Hunger strikers died throughout that summer, and in July it was the turn of Moss Side, Handsworth and Toxteth to blaze throughout the night. From marches backed by bureaucrats to half bricks hurled at heads, it really made no difference. As we know, she was not for turning. She expected it. She was ready.

And really, doesn’t the badge say it all? It’s the colour of the Emerald City; it’s a blank tarmac track without end. Doesn’t it symbolise a mirage on the horizon? The road to impossible dreams?

—

The Stranglers

Promotional badge (1981)

You didn’t score points by being into The Stranglers.

If you were once a teenage soul boy – whether of the sweaty, baggy northern kind, or the slicker, smoother southern variety – then your misspent years will have garnered you a bulging bag of cultural credit that can now be cashed in during 6 Music phone-ins or in the pages of Mojo. If you were light of skin and dark of temperament, and bunked your nervous way into inner city blues clubs, you could by now be earning a few handy bob writing the sleevenotes to lavish Brit-reggae box sets. And if you set up a Crass-styled commune and nourished your body on Sosmix, thrashing guitars and Gestetner ink, it’s time to launch your own production company and make the film of your life – because BBC4 wants to make you a star.

But if you saved your love for The Stranglers, I’m afraid you just got it wrong.

Jesus! The world was teeming with punk groups who could have contributed to your pension plan! Magazine, Wire, X Ray Spex. The Slits, Public Image or Joy Division (peace be upon them). Those post-punk documentary makers always need new talking heads and surely, Paul Morley can’t manage them all?

But The Stranglers? That glowering misogynist cartoon? Too pop, too pub, too prog. It was music for hod carriers drinking fizzy keg bitter. Like a CO2 belch in the face.

Front of stage, they were all toughness and menace; JJ Burnell with his top off and his bass slung at his waist looked very much like the iconic image of Sid Vicious in the depths of his dereliction. Hugh Cornwell was all confrontation and snarl: “Did somebody say wankah?” But behind them was an unlikelier pairing: Jet Black, an overweight ice-cream man on drums, older than my dad and sporting some distinctly un-punk under-chin stubble; and Dave Greenfield, whose keyboard ripples rose and fell like the Doors soaked in bad Guildford speed rather than LA LSD, and whose prog affections caused his hair to grow into a curious medieval bob, longish and centre-parted, and even triggered the sprouting of a lazy 19070s moustache that loitered on his upper lip like a fat black liquorice boot strap. He was a keyboard wizard of course; but I think he may have been an actual wizard too.

The early Stranglers were beery and brutish, jumping aboard the punk bandwagon as it rolled through Essex; appealing to those who’d been happy enough with Dr Feelgood or Eddie and the Hotrods, and who saw in punk the chance to continue supping brown ale while listening to fast guitars. As their career developed they succumbed to a weakness for concept albums and created their own impenetrable lore – witness The Gospel According To The Meninblack, which was a crazy concoction of UFO conspiracy and Biblical parody, half-baked together with a dash of Erich von Däniken – and that pulled in the neo-prog rock boys too; who were good at maths, and liked Jean-Michel Jarre, and devoured their copies of Strangled magazine for breakfast.

But crucially, The Stranglers knew how to squeeze out success from the unlikeliest of source material; bemoaning the lack of Shakesperoes in contemporary society, for example. They had hit singles, proper pop smashes, that you could whistle and which sounded good on Top of the Pops, and they kept them coming year after year, long after their contemporaries had either packed it all in or drifted too far into the mainstream. Indeed, those hit singles may be part of the problem; they simply had too many catchy melodies to their name.

So when it comes to attempting to establish a credible pop pedigree for myself, I may as well disregard the first gig I ever went to, the event that brought this badge into my life. It was The Stranglers on their La Folie tour, at Sheffield Lyceum, November 1981. An abandoned Victorian theatre turned makeshift music venue, I knew it only as the semi-derelict shell that sat across from The Crucible; having served time as a bingo hall in the 1970s, it was waiting for its number to finally come up and for the council to knock it down. But that Saturday night, I sat with my friends at the front of the circle and witnessed the whole exhilarating charade play out in front of me. It was the volume of the thing that astounded – and I suppose having ears that were just 14 years old didn’t help; when you’ve never experienced a genuine rock gig, it seems that nothing in human history can ever have been so loud. It was a noise that was physical, that was ringed by flame; but I discovered that if I put my fingers in my ears I could extinguish the fiery distortion and reveal the music hidden within. So that’s how I sat there for song after song; hypertense and amazed, fingers in ears; and ecstatic at the frenzy of the violence of it all.

We bought the badges, we bought the T-shirts, and our parents picked us up post-show and I found I couldn’t hear a word that anybody said. Someone had turned down life’s treble and placed a duvet inside my skull. I suppose I still carry with me the damage done that night; a fraction of the sonic world is lost to me and I can never get it back.

And would you believe it, I can’t even profit from the experience. Because this was not the Sex Pistols at the Free Trade Hall, or Larry Levan at the Paradise Garage, or The Ramones at CBGB. This was The Stranglers; and as we’ve ascertained, I’m afraid they just don’t count.

—

Cowen Barrett, Sheffield

Promotional badge (1979)

The clocks struck thirteen, and Britain gasped.

The Blessed Margaret: she’d finally got her claws dug in, right up to the knuckle, and as we Auld Lang Syned it and gawped at Kenny Everett, she began to crush the life from the decade’s last moments. She was right enough of course, as the veins popped out on her forearms and her wicked eyes bulged like Jaw Breakers; no more winters of discontent, no more paralytic prime ministers singing drinking songs to their union mates; it wasn’t the nineteen drib drab seventies no more. She was planning for years of new broomery, of cruel-to-be-kindness; of that jobs totaliser on the Ten O’Clock News clocking up minus figures night after night – a fruit machine spitting out UB40s; the devil’s own Blue Peter appeal.

Harsh times. So some people went into the 1980s with a smack addiction. Others lost their jobs, their homes, their marbles. But not me, oh no. Because, it seems, I went into the new decade with Cowen Barrett, a supplier of bathrooms (and kitchens, and heating!); so no wonder I had a spring in my step as I took my first tentative steps into the 80s’ unknown kingdom. How better to mark the onset of the decade of hip-hop, of house music, of hair gel, than with a chocolate-brown bathroom suite whose none-more-1970s colour scheme was about ten minutes away from going bang out of date; like voting Labour, and British Leyland, and black and white telly.

It was a colour scheme chosen to be in and of the moment – that exact moment, being the dying days of flares and bare feet and luxurious shag pile rugs, of hessian on the walls and Habitat tubular chrome. It was not designed to take account of changing global conditions – the creeping pastelisation of our world. This was not a bathroom built for golfing sweaters in shades of lemon or mint; for jump suits or ra ra skirts; for duck-egg blue Smart R’s so tight they could have been prescribed for varicose veins. Within months of the decade’s turn, it would become not only a dated looking bathroom, but a bathroom displaying the most unfashionable pigmentation it was possible to imagine.

“Chocolate brown? What were you thinking?“

I wasn’t thinking anything of course, except for “It’s a shit badge, but I’ll have it.”

I was just a kid.

The bathroom was my parents’ concern; their choice, their responsibility. Though as I pocketed the badge (not wearing it of course; I may have been a kid, but I wasn’t an idiot), mum impressed upon me and my sister the importance of cleaning away the scum ring after every soak. “If we’re going to have a bath as nice as this one,” (like a hollowed out Mars Bar), “we’ve all got to do our bit.”

So I did do my bit, scrubbing away at the chalky deposits as the water screwed its way down the plug. And as the new decade grew up, and I grew up too, I tried to do my bit in other ways, attempting to wipe away the troublesome Tory tide mark by wielding revolutionary newspapers and shouting a lot. Which, rather more than that bathroom, turned out to be the most outdated choice of all.

—

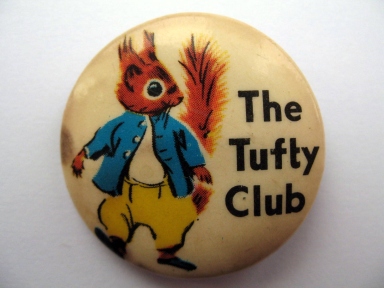

The Tufty Club

Membership badge (early 1970s)

It was always a thrill to see policemen at school. They towered over Miss Clarebra, the infant school’s Head, who would beam at them; smiling a smile we’d never previously witnessed – old-skool ma’am that she was, always ready to slipper a five-year old if the occasion demanded it, dispensing rubber-soled justice to those meddlesome children who would insist on behaving like… erm… children.

The policemen, a little nervous and polite, would carry their helmets, and bend down to pass through doors, and children would tail them through the corridor just wanting to be close, to absorb the power of the goodness that they believed must radiate from within.

The officers would be introduced in assembly, or perhaps they would visit us in our classrooms, and they would tell us how to cross the road, like Tufty. He was a squirrel who was learning the Green Cross Code, the ancient lore that instructed us in the whys and wherefores of not being flattened by traffic. He was a good squirrel, from a good home; sometimes he got things wrong, and was mildly rebuked – for suddenly emerging from behind an ice-cream van perhaps, or for running into the road for his ball. He would hang his head and accept the chastisement; and because we knew that Tufty was our representative in this woodland suburbia, we – for the most part – wanted to act like Tufty. To behave like Tufty. To submit like Tufty.

Look right, then left, then right again.

Having dispensed their sombre lectures, the policemen would then recruit us into the ranks of the Tufty Club, which meant badges, and booklets, and an invitation to their annual film show; which sounds like the sort of thing that might have been held in a dusty church hall, but was in fact a big-screen extravaganza that took place in the Sheffield ABC each Christmas; and it was a big screen, being years before such cinemas were sliced up and boxed off into parcels; it was massive, and splendid, and not like TV. The main feature would come courtesy of the Children’s Film Foundation – kids foiling bank robbers or finding some treasure, like an elongated episode of The Double Deckers. And there would be road safety films too, and a man-sized Tufty would be led onto the stage – shuffling, and sightless, and mute.

Someone would model a balloon and give it to a child from the crowd. And policemen – more of them, the school-visiting kind – would cradle their helmets in the crook of an arm, and repeat and repeat and repeat: right, then left, then right again. Right again. Right again.

We learnt it, and spoke it, and felt it.

It was our mantra for the times yet to come.

—

Warlord Comic

Membership badge (mid-1970s)

I blame the boys who lived down the road; one older than me, one younger. They were a pair of brothers whose favourite game was war; it was something they knew about, were interested in; they could always ID the uniforms on those tiny soldiers who came attached to a rectangle of plastic. They had battalions of them, entire armies of moulded polythene killers; you could arrange them in wave after wave on their utility room steps, till the wind came up and sent them tumbling to their miniature doom.

They were boys with pea shooters and catapults, arrows and bows. The eldest had a Chopper, a bike that elderly neighbours whispered was “dangerous” – something they’d heard on the news, and meaning, I think, that it was the two-wheeled choice of the naughtier brand of boy. They had an arsenal of cap guns, and rolls and rolls of the spiralling paper explosives that gave them their sour-scented CRACK! They had toy daggers and Action Men, and they were cheeky to passers-by. I was in awe of them, and scared of them; but they were exciting, so I made them my friends.